Green Teaching Summit: A Humanities Approach to Climate Education

Faculty connect, learn about campus climate and ecology resources at the Green Teaching Summit convened by Tolley Professor Mike Goode at Syracuse University’s Minnowbrook Conference Center.

Green Teaching Summit attendees gathered beside the lake at Minnowbrook Conference Center in the Adirondacks.

Can religion, philosophy, history, English and writing help tackle issues of climate change, environment and ecology? Absolutely, says Mike Goode, professor of English and outgoing William P. Tolley Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Humanities. Through his Tolley professorship, a role designed to support enhancement of the pedagogical experience and to boost effectiveness in the classroom, he made it a goal to show how the humanities subjects are vital to helping society understand and respond to today’s complex ecological challenges. Here are just four of many ways humanists are engaged in research relating to climate:

A. More Than Just a Map – While maps depict selected data about a place, humanists play a key role in translating and communicating what maps say about power, representation and climate urgency - crucial insights for leaders making decisions about the allocation of resources and implementation of policies.

B. Losing Languages – Climate change doesn’t just affect the physical world. It affects human culture, too. When climate change causes people to leave their homeland, they often also lose their language. Through the study of language endangerment, humanists examine the causes, processes and consequences of languages becoming extinct and work on ways to preserve them.

C. Religion and Ecology – Religion scholars might explore the environmental consequences of festivals and pilgrimages that draw millions of people to a concentrated area. Or, research on sacred texts can delve into how the texts shape environmental consciousness in different faith traditions, highlighting political issues and raising doctrinal concerns.

D. Human-Animal Entanglement – Bestiaries, or works about mythical animals, can spark discussions about human-animal entanglements in different countries and contexts.

A main component of Goode’s professorship was highlighting opportunities for faculty and staff across campus to share resources to help students respond to the implications of the climate crisis and to think ecologically.

Inspired in part by the success of a collaboration with the SU Art Museum where Goode teamed up with staff and students to explore the ways in which objects and artworks in the museum’s collection could be utilized as resources to teach about ecology and climate, he wanted to see how others at the University could forge partnerships to elevate their own research and teaching around ecology. In May, he convened a team of faculty from numerous humanities disciplines at the Green Teaching Summit at Syracuse’s Minnowbrook Conference Center in the Adirondacks. The three-day conference provided a space for scholars to discover shared interests and forge collaborations, set in a location that itself is ecologically vulnerable.

The Minnowbrook Conference Center entrance, left, and facade, right, which greeted attendees of the Green Teaching Summit when they arrived.

Arts and Sciences Communications (A&S) sat down with Goode (MG) to talk about his motivation for the summit and how the humanities play a crucial role in sparking ecological discussions.

A&S: Why is now such a critical time for humanists to focus on ecology and climate?

MG: When doing my English Ph.D. in the early 1990s, I remember one of my professors, Homi Bhabha, declaring that whatever our training and expertise in the humanities, every humanities course would soon need to engage in some way with the histories of colonialism and empire. His comment encountered considerable audience skepticism at the time, but it turned out to be prophetically accurate. We’re facing a similar turning point in the humanities. Whatever our training or expertise, we are likely less than a decade removed from a time when every one of our courses will need to engage with ecology, climate and environmental justice in some way. As the Tolley Professor, I focused on trying to help the humanities at Syracuse University lean into this coming shift and to increase their visibility on campus for doing so.

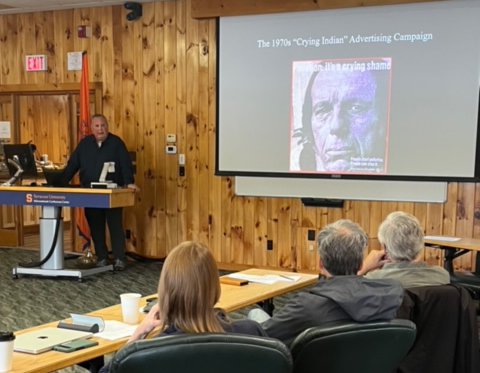

Summit Topic: The Haudenosaunee Ethos of Sustainability – Scott Manning Stevens, associate professor of English and director of both the Center for Global Indigenous Cultures and Environmental Justice and Native American and Indigenous Studies program, talked at the conference about the Haudenosaunee commitment to the environment. He shared an example which he uses in class, referencing the Seventh Generation Principle, a Haudenosaunee philosophy for decision making which asks, “seven generations down the road, will you be condemned for the environmental decisions you made today, or will you be celebrated and appreciated?”

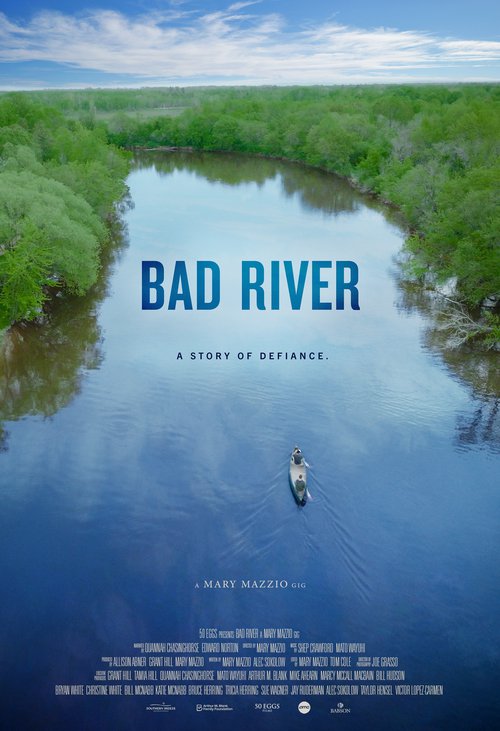

Stevens also spoke following a screening of the 2024 film, Bad River, which chronicles the Wisconsin-based Bad River tribe and their ongoing fight for sovereignty. The film delves into the Band’s ongoing battle over the fate of an oil and gas pipeline running across northern Wisconsin, which poses a potential environmental threat to Lake Superior. Stevens, who is a citizen of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation, was interviewed in the film directed by Mary Mazzio.

A&S: What was the inspiration for the Green Teaching Summit?

MG: Since the Tolley professorship is charged with expanding and improving humanities teaching, I wanted the summit to be a humanities-focused event with faculty from various environmental disciplines. I wanted as many of the most recently hired tenure-track humanities faculty as possible to attend along with staff who could highlight ways to further leverage campus resources, so the next generation of humanities scholars are empowered with the critical perspectives necessary to help raise awareness, inspire action and help shape policies that are socially just and culturally sensitive.

In between presentation sessions, faculty mingled with one another to discuss collaborations on the shores of Blue Mountain Lake.

Resource Spotlight

Throughout the weekend, presenters from across campus shared teaching resources available to faculty.

Vivian May (standing, right), professor of women’s and gender studies and director of both the Syracuse University Humanities Center and CNY Humanities Corridor, talked about advancing ecology, climate and environmental justice teaching and research through the Humanities Center and the Corridor.

Jolynn Parker, director of the Center for Fellowship and Scholarship Advising, discussed national scholarship opportunities for students interested in sustainability.

Kate Holohan, curator of education and academic outreach at the SU Art Museum, explained how faculty can become involved in ecological object-based teaching at the art museum.

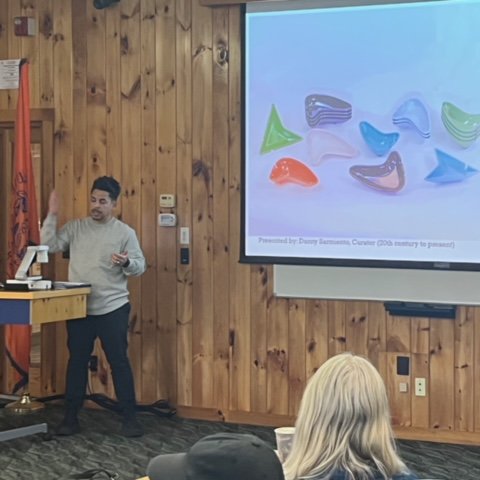

Danny Sarmiento, curator at the Special Collections Research Center, shared information about ecology, climate and environmental justice-related collections and texts in the Special Collections Research Center.

A&S: What do you hope that faculty can take away from this experience?

MG: I had three goals:

- Have people on campus who already teach in these areas connect with one another, describe what they do in the classroom, learn more about how different subjects get taught from different disciplinary vantage points and plant the seeds for future initiatives and collaborations.

- Highlight campus resources, centers and offices with which to collaborate on experiential learning, student success and professional development related to ecology, climate and environmental justice concerns.

- Bridge generations, connecting the newest tenure-track hires in the humanities at Syracuse to senior faculty on campus already teaching and researching in these areas, so we could mutually inspire, learn from and collaborate with each other moving forward.

A&S: What are the benefits of having a group of scholars (and administrators) come together at a summit like this? Do you think that the setting was/is particularly important?

MG: One bit of feedback I have received repeatedly from attendees is that they did not realize just how many other people on campus were teaching in these areas and were thrilled to meet faculty with shared interests who they might not have met otherwise. The Adirondacks setting, however aesthetically pleasing, also probably contributed to a sense of urgency, since some of the weekend’s talks touched on the region’s ecological vulnerability and its connection to histories of environmental injustice through Native American displacement and dispossession.

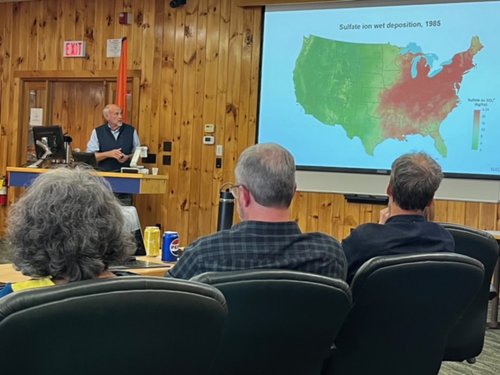

Summit Topic: The Impact of Climate Change on the Adirondacks - Charles Driscoll (pictured, at podium), University Professor of Environmental Systems and Distinguished Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering in the College of Engineering and Computer Science, presented a talk titled, “The Adirondack Park and its lakes.” His presentation touched on how human-caused climate change has altered the Adirondacks. Specifically, the combustion of fossil fuels has increased acid rain and mercury levels, forcing people to limit their consumption of fish, such as yellow perch, caught in Adirondack lakes.

Key takeaway: “In engineering, I rarely get to meet anyone in the humanities. I got a lot of great ideas from being here. For example, I will meet with Professor Scott Stevens soon because I have a project within an Indigenous community and want to be sure that I deal with elders sensitively.”

A&S: Understanding that you are wrapping up the two-year Tolley professorship this summer, what do you hope the legacy or potential of the Green Teaching Summit will be at SU?

MG: I’d love it if a dedicated environmental humanities chair could be created on campus to continue expanding and sustaining this kind of environmental humanities-focused programming, network-building and resource-sharing. We need people and resources to spearhead more humanities-centered working groups and to develop new campus collaborations related to ecology and climate. The Art, Ecology, and Climate Project (that I founded while Tolley Professor) is already being used in many different instructional contexts on campus, and I hope that it can eventually be grown to include holdings at repositories like SCRC and the Belfer Sound Archive. Unfortunately, climate change is the shared future of all of us, and every single faculty member needs to be positioned instructionally to grapple with it. I certainly hope that the newest humanities faculty on campus walked away from the summit energized to lean into that project more in their own teaching moving forward.

Presenters included: Arun Brahmbhatt, assistant professor, religion; Boryana Dragoeva, professor of art video, VPA; Kate Holohan , curator of education and academic outreach, SU Art Museum; Charles Driscoll, University Professor of Environmental Systems and Distinguished Professor, College of Engineering and Computer Science; Mike Goode, professor of English and William P. Tolley Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Humanities; Josh Hunt, assistant professor of philosophy; Tanisha Jackson, assistant professor of African American studies and executive director of the Community Folk Art Center; Denisa Jashari, assistant professor of history, Maxwell; Meghan Kelly, assistant professor of geography, Maxwell; Vivian May, professor of women’s and gender studies and director of both the Syracuse University Humanities Center and CNY Humanities Corridor; Edward Morris, professor of practice, VPA; Cristina Pardo Porto , assistant professor, Languages, Literatures and Linguistics (LLL); Jolynn Parker, director of the Center for Fellowship and Scholarship Advising; Cary Penate, assistant professor of music history and cultures; Sarah Pralle, associate professor of political science, Maxwell; Romita Ray, associate professor of art history; Daniel Sarmiento, curator, Special Collections Research Center; Susannah Sayler, associate professor of art photography, VPA; Erica Shumener, assistant professor, philosophy; Adam Singerman, assistant professor, LLL; Scott Manning Stevens, associate professor of English and director of both the Center for Global Indigenous Cultures and Environmental Justice and Native American and Indigenous Studies; James Watts, professor, religion; Joseph Wilson, assistant professor of writing and rhetoric; Bob Wilson, associate professor of geography, Maxwell; and Martin Zavaleta, assistant professor of philosophy.