Heart of a Lion

Friends remember biology professor Marilyn Kerr, who died at age 82

When Marilyn Kerr arrived at Syracuse in 1970, science was a male-dominated profession. The idea of a woman donning a white lab coat and waxing rhapsodic about biology or chemistry seemed, in those days, about as likely as someone synthesizing a gene or performing a bone-marrow transplant. It just wasn’t done.

Leave it to Kerr, who died on Oct. 6, at age 82, to shake up things in Syracuse’s then-nascent Department of Biology. For four decades, she served on the front lines of the College of Arts and Sciences—climbing to the rank of associate professor of biology; serving as principal advisor of the Biology Undergraduate Program; and directing the Health Professions Advisory Program (HPAP), in which she helped prepare students and alumni from Syracuse and SUNY-ESF for careers in the health professions, including veterinary medicine.

Kerr also made employment equity and stereotyping part of the national conversation. Her important work coincided with the second-wave feminism of the 1970s, paving the way for many changes at Syracuse. Among her contributions was assisting in the conceptualization of the Life Sciences Complex (LSC), under the leadership of then-A&S Dean Cathryn Newton. LSC, which opened in 2008, is an academic and architectural marvel, home to a diverse, yet unified, faculty from all walks of life.

“Marilyn was a tiny woman with the heart of a lion,” says Margaret Voss G’02, professor of practice in public health, food studies and nutrition in Falk College. “She had wisdom beyond imagination and a sense of humor that brought mirth to unexpected places. I really miss her.”

Kerr also had an independent streak, which could be endearing or intimidating, depending on which side of the desk you sat on. Born in the small Illinois city of Sumner (founded by her great-great-grandfather), she spent her formative years in New Jersey, going to school and working a parade of part-time jobs, including waitressing, coaching and serving as a camp counselor.

In 1957, Kerr spent a year in Iran, where her dad was working with Texaco. Fresh from earning a biology degree from Gettysburg College, she scored a lab position at one of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co.’s many hospitals. Her off hours were spent soaking up the country’s sights and sounds and, in the evenings, dancing with American GIs stationed there.

“That trip influenced many of her interests for the rest of her life,” says Kathryn Tunkel, an administrative assistant in Falk’s sport management department, who used to work with Kerr in HPAP. “Marilyn was an avid reader, and particularly appreciated historical and mystery novels. She also was a connoisseur of good food—someone who didn’t flinch at the idea of driving several hours to a fine restaurant. She loved traveling and trying new things.”

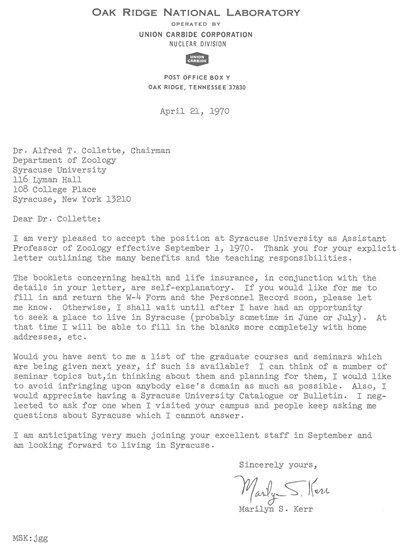

Going on to Duke University, Kerr focused on zoology, a branch of biology involving animals—their structure, embryology, evolution, classification—and how they interact with their ecosystems. She earned a master’s degree, and then became Duke’s second woman to be awarded a Ph.D. in zoology. Her Southern sojourn culminated with back-to-back fellowships at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and a part-time teaching gig at Knoxville College, a historically black liberal arts institution. More than anything, she wanted a tenure-track position.

Kerr almost didn’t come here. As the story goes, the University of Minnesota made her a better offer, which Syracuse countered. “I don’t want a stopgap position,” Kerr told Alfred Collette, then chair of Syracuse’s zoology department. “I will go wherever I think I can be more effective as a teacher, and, of course, where I can establish a good laboratory and continue to be active in research.”

The situation was exacerbated by a strike at Oak Ridge, where workers rejected a wage proposal by Union Carbide (which operated the laboratory), thus delaying the receipt of Kerr’s faculty appointment letter. When weeks passed without a word, Collette sent a follow-up note, oblivious to the fact that her acceptance letter was on its way to him.

Although biology has been taught at Syracuse since 1873 and was an academic unit in the 1890s, it did not become the Department of Biology until 1970, with the merger of the zoology and plant sciences departments. Kerr’s research portfolio complemented Syracuse’s growing interests in molecular, cell, organismic and population biology. (Today, the biology department focuses primarily on cell signaling and bio-complexity.) Kerr is remembered for teaching several laboratory-associated courses, the most popular of which was embryology, and for designing a lecture course on developmental biology. She also pioneered a course on comparative vertebrate biology, incorporating Apple’s fledgling interactive videodisc technology. Replete with photography of slides and specimens, Kerr’s videodiscs were produced by Barbara Grabowski, then a Syracuse professor who would go on to make a big noise in the field of instructional systems.

Ghaleb Daouk ’79, a pediatric nephrologist and director of extramural programs at Boston Children’s Hospital, remembers taking Kerr’s advanced embryology course during his senior year. Like most pre-med students, he expected to “ace” the course, in hopes of getting into a good medical school. The final exam, however, turned out to be harder than expected, so he wound up with a B in the course.

“It was disastrous,” says Daouk, also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and a longtime member of the A&S Board of Visitors. “With great revolt against this defeat, I requested a meeting with Dr. Kerr to prove to her that I truly enjoyed and understood the material.” Their 15-minute appointment turned into a 45-minute mini-oral exam, after which she paused, closed Daouk’s exam booklet and smiled at him. “She was convinced that I knew the material, but was a poor exam taker. I got an A.”

Daouk is one of many former students who recalls Kerr’s warm personality and genuine interest in people. “I have never seen a more patient and dedicated pedagogue,” he continues. “Her deep care for biology and her students were unique ‘Marilyn Kerr’ traits. They made a deep impression on me and on my own approach to pedagogy.”

Indeed, Kerr had clout with her colleagues, but she also didn’t take herself too seriously. On her CV, of all things, Kerr noted that during her “tenure ordeal,” she submitted three papers for review and had another in preparation. “I just said [to] hell with ’em,” she added at the bottom of the page. Pure Marilyn.

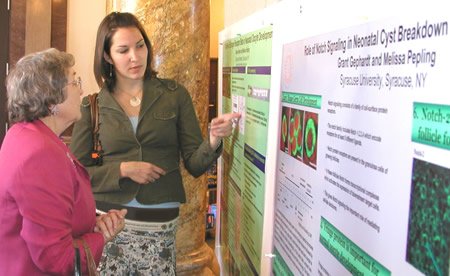

In 1990, after two decades of full-time teaching, Kerr threw herself into student advising. She still taught biology part time, but, as HPAP’s director, wanted to find other ways to help students reach their full potential. That meant a lot of writing, as evidenced by countless letters of recommendation that Kerr penned for students applying to professional schools. She also wrote, edited and published Caduceus, HPAP’s monthly newsletter; “Words to the Wise,” a four-year guide for incoming first-year students interested in pre-professional studies; and “Prescriptions,” a collection of educational materials for students studying podiatry, dentistry, optometry or medicine.

Kerr also helped usher Syracuse into the digital age by developing and maintaining HPAP’s website—one of the first websites on campus—which eventually was taken over by the Association for American Medical Colleges.

When she wasn’t supervising honors thesis projects, graduate dissertations or internships, Kerr served on boards and committees. She was particularly involved with the Northeast and National Associations of Advisors for the Health Professions.

Kathryn Tunkel chalks up Kerr’s success to asking students the right questions and getting them to think strategically about their careers. “Marilyn was known for her frankness, honesty, knowledge, thoroughness and professionalism,” Tunkel says. “She also was appreciated for her sense of humor and that twinkle in her eyes.”

Case in point: Robin Hemphill ’91 wanted to go to medical school, but didn’t think she needed someone to walk her through the process. “When I finally realized that I needed an advisor,” she says, “I made my way to Marilyn, who sat me down and asked me an important question: ‘Why do you want to be a doctor?’ I couldn’t imagine why I needed to answer such an obvious question, so I promptly said, ‘Because that’s what I want to do.’”

Embarrassed, Hemphill slunk back to her dorm room and mulled over Kerr’s question. Today, the former biology major is the acting assistant deputy under the secretary of health for quality, safety and value at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “Her practice interview for medical school was the toughest I ever had,” says Hemphill, who graduated from the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “She prepared me well.”

Margaret Voss, Kerr’s teaching assistant in the late ’90s, echoes these sentiments. She remembers when Kerr and Eleanor Maine were the only tenured female professors in the biology department. “I knew very few female Ph.D.s when I landed on Dr. Kerr’s doorstep,” Voss says. “She quickly became the role model I didn’t know I needed. Her quick wit, wonderful sense of humor and iconic laugh made a lasting impression on me.”

The same may be said for Kerr’s resilience. Voss recalls being assigned to her when Kerr was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. “For three years, we laughed and cried together,” Voss says. “She helped me make major life decisions, and taught me to hold high standards and my ground when necessary. Marilyn also showed me the importance of frank honesty and compassion. ... I’ve learned how to be an academic, how to face adversity in life and how to write a mean anatomy exam, thanks to her.”

Kerr earned considerable hardware during her career—an Outstanding Faculty Advisor of the Year Award, a Chancellor’s Inspiration Award and an Exemplary Service Award for her involvement with Syracuse’s Career Services department. But it was her selfless devotion to students and members of the campus community for which she is largely remembered. “She was an ‘on-call’ consultant for the children of faculty, staff and friends who didn’t attend Syracuse, but sought to attend medical, dental or veterinary college,” Tunkel says incredulously. “It was like an ad-hoc post-baccalaureate advisory service. Many health care professionals from Syracuse and beyond owe their successful transition into post-baccalaureate training to Marilyn.”

Biology major Shazia Bég ’02 didn’t think she had a shot at getting into an American medical school. “I was an international student at Syracuse, but was told by others that it would be near-impossible for me to get accepted,” says Bég, assistant professor of internal medicine and rheumatology at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine. “With Dr. Kerr’s constant encouragement and guidance, I was accepted to SUNY Upstate [Medical University] on my first try. She always welcomed me into her office with a smile—and chocolates—and provided the most experienced, well-balanced advice. Her dedication to her students was truly commendable.”

Perhaps the best example of Kerr’s selflessness was a generous gift she made to the biology department, resulting in an eponymously named graduate scholars endowed fund. A few weeks before her death, Kerr recognized the fund’s inaugural recipient—Emma Whittington, a Ph.D. student in evolutionary biology—at a private ceremony at The Nottingham, a senior living community close to campus.

Among those in attendance was Ramesh Raina, associate professor and chair of biology. He says that, even in death, Kerr’s impact has been lasting. “Her passing is a great loss to us,” Raina says. “At the same time, her legacy lives on in her philanthropy and generations of students. She made Syracuse a better place.”

Samuel Gorovitz says the University would do well to remember Kerr. “Marilyn quietly and modestly toiled through a long career, often far from the limelight,” says the professor of philosophy and former dean of A&S. “But she has lit a very bright light within her department with her gift in support of women in science. Beyond that, her philanthropic example is a gift to the University.”

Editor’s Note: An on-campus celebration of Kerr’s life is scheduled for Thursday, Nov. 3, at 4 p.m. in Hendricks Chapel. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the Marilyn Sue Kerr Graduate Scholars Endowed Fund, Syracuse University, 820 Comstock Ave., Syracuse NY 13244.