A new, NIH-funded trial aims to offer new solutions for stroke survivors with aphasia and post-stroke fatigue.

Two conditions frequently emerge after a stroke: aphasia and post-stroke fatigue. While each condition alone presents significant hurdles to recovery and quality of life, their combination creates a uniquely difficult burden for patients.

Aphasia affects approximately one-third of stroke survivors and may hamper their ability to communicate effectively. This language disorder impacts word finding, sentence formation and language comprehension — all while leaving cognitive abilities intact. The frustration of being unable to express thoughts, needs or emotions can be profoundly isolating for someone with aphasia.

Even more prevalent is post-stroke fatigue, which some research suggests may impact between 70 and 80 percent of stroke survivors.

“We think about post-stroke fatigue as something that's a little bit different than what we would consider fatigue,” says Ellyn Riley (pictured), associate professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. “So just your everyday person, if you say, 'Do you ever experience fatigue?' Most of us will say yes, but post-stroke fatigue is much more debilitating and difficult to recover from. It's fatigue that's basically defined as not being recoverable by rest the way we would expect. This is something that's a chronic issue."

Fighting Fatigue

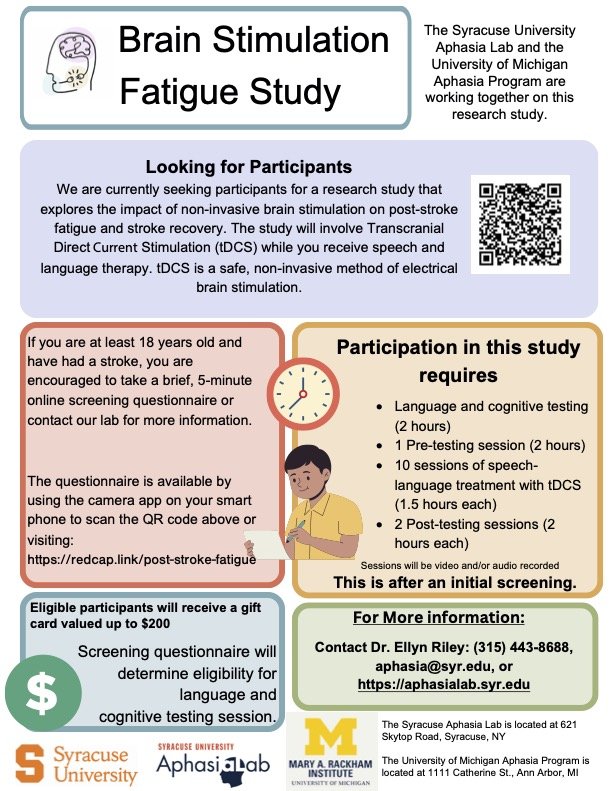

Riley serves as the principal investigator at the Syracuse University Aphasia Lab, which, alongside the University of Michigan Aphasia Program, is recruiting participants for a research study investigating brain stimulation to help reduce fatigue and improve language and cognitive recovery for people after a stroke. The groundbreaking clinical trial aims to address both aphasia and post-stroke fatigue simultaneously through an innovative approach combining brain stimulation with speech therapy. The research represents the convergence of multiple disciplines — neurology, speech-language pathology and neurophysiology — in tackling these persistent post-stroke challenges. The study applies transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), a technique that delivers low electrical current to specific regions of the brain, making them more easily activated. This stimulation occurs concurrently with evidence-based speech and language therapy.

The researchers received a $3.7 million grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIDCD conducts and supports research in the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech and language.

The work holds personal meaning to Riley, who first encountered aphasia with a personal experience.

“My grandmother had a stroke when I was in high school and at the time I had never heard the word aphasia,” she recalls. “She was a writer, so it was particularly impactful for her not being able to express herself in the way that she was used to. I saw the firsthand effects of that, and it wasn't until I was in college I took some undergrad linguistics classes and I learned about what aphasia was. And I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, that's what my grandmother had.’”

The research builds upon existing knowledge while venturing into uncharted territory. While tDCS has been studied for aphasia treatment, and post-stroke fatigue has been examined in relation to physical impairments, this study pioneers the specific combination of tDCS for treating fatigue in aphasia patients.

"We previously had an NIH-funded study using tDCS with the same population," Riley notes, "but in that study, we were focused mostly on improving attention and language. In this study, we're applying a similar approach to also treating post-stroke fatigue."

The fully blinded clinical trial compares active tDCS versus sham (placebo) stimulation. Neither participants nor clinicians know which condition is being administered, ensuring the scientific validity of the results.

Participants first complete an online screening, followed by comprehensive language and cognitive testing if they qualify. A neurologist reviews each candidate's MRI scans to confirm eligibility. Treatment sessions, lasting approximately 90 minutes each, combine electrode setup with an hour of speech therapy conducted by certified speech-language pathologists.

The researchers are additionally investigating whether attention-based treatment or language treatment that is less attention-focused produces better outcomes. Pre- and post-testing measures track improvements in language function, fatigue levels and cognitive abilities.

While the study is still in its early stages, with recruitment currently underway, Riley is optimistic about its potential and hopeful that active tDCS will lead to greater reduction in fatigue symptoms and improved language outcomes compared to the placebo condition.

If successful, this research could transform the approach to post-stroke rehabilitation, addressing not just the communication challenges of aphasia but also the debilitating fatigue that often accompanies it. For stroke survivors facing these dual challenges, such comprehensive treatment could significantly enhance recovery and quality of life.