by John H. Tibbetts

A&S professor Xiaoran Hu has developed molecules that undergo mechanochemical transformations, which could be used to report nanoscale stress in plastics and help scientists study mechanobiology processes.

Key Takeaways:

- Scientists set new mechanosensitivity benchmarks in mechanically induced chemical reactions.

- These molecular force sensors could enable “smart” plastics that self-report mechanical deformation and damage, promising for use in critical infrastructure elements like buildings and bridges, structural components in cars and airplanes, and wearable motion tracking devices.

- The ultrahigh mechanosensitivity may also aid the study of previously unobservable mechanical events in biology.

Plastic components are commonly used in infrastructure and transportation that we depend on—from water and sewer pipes to planes, trains and automobiles. But plastic materials experience stresses that degrade them over time. That’s why plastics in many critical applications are replaced on pre-set schedules, which is expensive but crucial for maintenance and public safety.

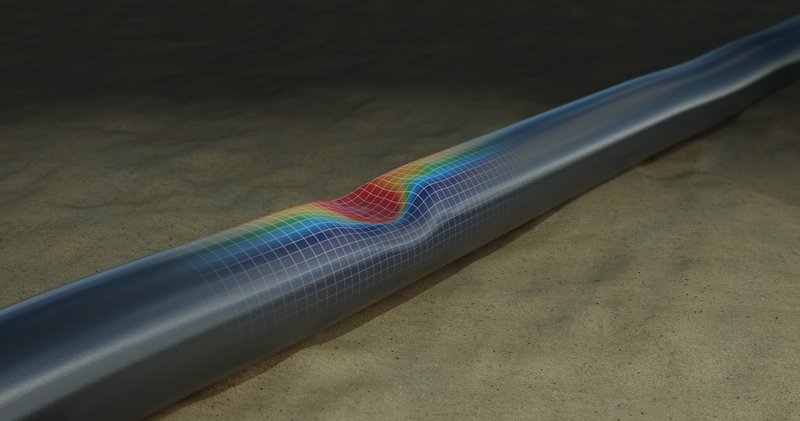

Molecular force sensors developed by Syracuse University chemist Xiaoran Hu could pave the way for 'smart' plastics that self-report mechanical deformation, such as when pipes degrade. (Courtesy: Shutterstock)

“When mechanical forces cause stress and deformation that go unnoticed in the plastic engineered parts of an airplane, for instance, it can cause significant consequences that we want to avoid,” says Xiaoran Hu, assistant professor of chemistry and member of the BioInspired Institute at Syracuse University.

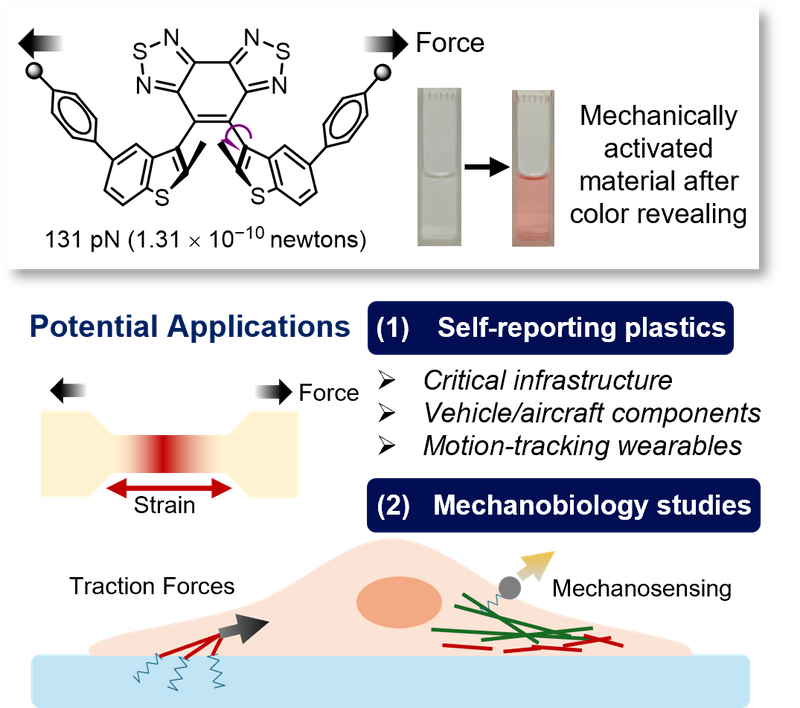

Supported by Syracuse University and the ACS Petroleum Research Fund, Hu and his team have created new molecules that someday could cut down on these risks and expenses. Mechanophores are molecules that respond to mechanical stress by changing characteristics such as their colors, and their incorporation into plastic components could enable visualization of mechanical stress. Hu’s team developed exceptionally sensitive mechanophore molecules—called “configurational mechanophores,”—that undergo mechanochemical isomerization reactions. The activated material can exhibit a color to indicate that a mechanical event has happened in a component. This visible signal would be useful in applications such as autonomous damage monitoring of materials.

“These new molecules could enable research into previously unobservable mechanical events in different materials, including synthetic plastics and biomaterials,” says Hu.

Ultrasensitive molecular force sensors facilitate structural health monitoring in plastic components and could enable scientists to investigate previously unobservable mechanical events in biological systems.

The Syracuse team’s mechanophores are unique. According to a new study in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, their chemical transformation is triggered by minus mechanical forces as low as 131 piconewtons, which is below what is required to trigger any other mechanochemical reactions known up to date. For comparison, mechanochemical reactions involving carbon-carbon bond scission typically require nanonewton scale of forces (1 nanonewton = 1000 piconewton). Hu’s mechanophores, on the other hand, are more sensitive than the tiny forces relevant in many biological molecules, such as the unzipping of DNA strands (~300 pN), the unfolding of protein domains, and the breaking of antibody-antigen bonds (~150-300 pN). The new mechanophores could be effective tools in biology, allowing scientists to study stress changes at the nanoscale that were previously unobservable or difficult to measure. This could lead to a better understanding of how mechanical forces influence and regulate various processes in biology.

Additionally, unlike most traditional mechanophores, which are prone to damage by heat or light, the new molecules are stable upon thermal and light exposure, and therefore are well suited for applications in different complex environments.

Hu’s research on configurational mechanophores paves the way for the development of mechano-responsive materials with unprecedented mechanosensitivity. These materials could enable the study of previously unobservable nanoscale mechanical behaviors, playing a crucial role in advancing our understanding across scientific disciplines ranging from polymer physics, materials science, to mechanobiology.

“Our lab is developing the next-generation molecular force sensors with further enhanced mechanosensitivity and capable of exhibiting fluorescence signals or other functional responses,” Hu says. “We also aim to apply our mechanophores to different materials platforms such as mechanosensitive elastomers and paints to develop safer and smarter plastics that autonomously monitor and report mechanical damage. Additionally, we will explore the potential of these molecular force sensors to investigate cellular processes in the future.”