by John H. Tibbetts

Each fermented food—kombucha, sauerkraut or sourdough bread—is the result of an active, unique microbiome, which is the microbial community in a particular environment. A sourdough starter, for instance, is a distinctive community of yeasts and bacteria that ferments carbohydrates in flour and produces carbon dioxide gas, making bread dough rise before baking.

Microbiomes often bump into each other, such as when two people shake hands. They can trade microbes while keeping their original integrity intact. But microbiomes can be accidentally or purposely mixed, creating new microbial systems and functions. Agricultural soils and their microbiomes are often blended and reassembled to improve crop productivity.

Scientists term these mixing events as community coalescence, but little is known about this process or its outcomes.

“We have a poor understanding of community coalescence,” says Angela Oliverio, an assistant professor of biology. “We lack a theoretical framework to help predict what happens during coalescence, and we lack model systems to test its effects.”

Oliverio has been awarded a National Science Foundation grant to study the mechanisms of community coalescence in synthetic microbiomes constructed in the lab. Her team uses microbial model systems that are easy to culture and replicate.

“We aim to learn how microbiomes reassemble when they mix,” she says. “We want to see how mixing events impact the function of microbiomes and how often new communities with novel functions form.”

The Olivero lab houses a library of 500 global sourdough starter samples previously collected from community scientists globally. Her co-investigator at Tufts University has developed a library of kombucha samples.

The researchers are addressing fundamental questions about how complex systems work.

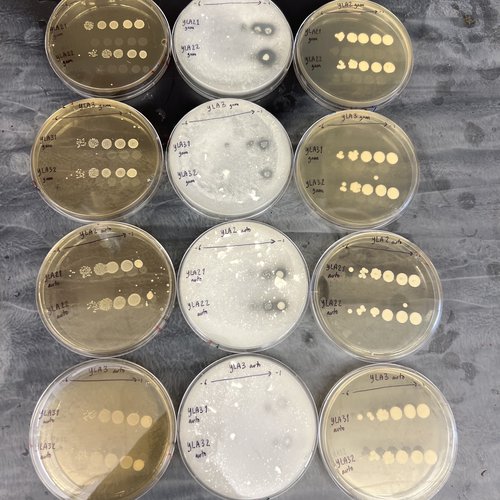

“We are culturing different isolates from these wild samples that we can then put together in synthetic communities and coalesce them with each other,” Oliverio says. “We will use genomics tools to see if there are attributes at the genome level that we can use to predict how coalescence will occur.”

Oliverio’s team plans to use RNA tools to understand how the transcription of communities shifts when they encounter another community or microbiome.

“These genomic tools could offer us hypotheses about how this process occurs at a metabolic level, so we can predict which community components will be successful,” says Oliverio. “But we also think we can develop useful tools for microbiome engineering with a potential to improve manipulation of microbiomes that are relevant to medicine and industry.”

Oliverio plans to take advantage of the appeal of fermented food systems to increase public interest in microbiology.

“People have questions about food, especially sourdough starters, and that’s a good way to connect with people and perhaps get them excited about microbiology," she says. "Everyone wants to tell me about their sourdough starter, and that’s a starting point for a conversation.”

She is developing an undergraduate course in computational biology and genomics, using sourdough starters as a “charismatic tool” to learn those topics.

“The idea is that students will start their own sourdough culture, isolate microbes from it, sequence those microbes, and then learn how to assemble and analyze genomes from their own sample.”