Editor's Note: The following article was written by H. Richard Levy, professor emeritus of biochemistry, and recounts his experiences as a child escaping Nazi Germany. It first appeared in the Department of Biology's Fall 2010 magazine, "Biology@SU." Levy recently published a full length memoir titled, "Recollections and Reflections From My Life in Nazi Germany, Wartime England, and America."

H. Richard Levy and his daughter, Karen, at the monument to Felix Mendelssohn (a distant relative) in Leipzig. Although Mendelssohn converted to Christianity, the Nazis still considered him a Jew, and his music was banned and the original monument destroyed. The present monument was rebuilt after the war.

In October 2009 I was given an extraordinary opportunity to visit my hometown in Germany for the first time in over 70 years. Here I will share with you the story of this journey and reflect upon some of the memories it stirred up. Before I do, I need to tell you about the events that led up to my leaving Leipzig, where I was born and where I spent the first nine years of my life during a time when Jews were increasingly subjected to oppression. I was incredibly lucky to escape to England in 1939, as I will describe shortly.

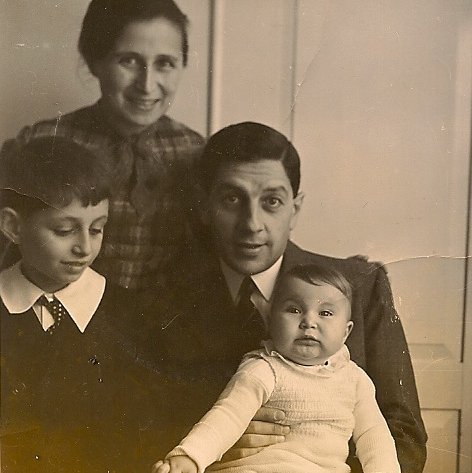

After Hitler came to power in 1933, the situation for German Jews steadily deteriorated. It reached a climax on Kristallnacht, (the night of the broken glass), November 9, 1938, when Jewish shops and synagogues all over Germany were destroyed and thousands of Jewish men were arrested. It is one of my few clear memories from that time. Early in the morning on November 10, men pounded on our apartment door and shouted vile epithets about Jews. They told us to assemble immediately at a nearby location. It was a raw day, and we dressed warmly. At the last minute, my mother decided not to take my little sister, then only 10 months old, but left her with our trusted maid. I walked between my parents, holding their hands. I was 9 years old and very frightened. As we got closer to the place, I heard loud banging, and I thought: they are killing Jews in there. But it turned out to be a shoe factory, and the whole thing was just a hoax to torment Jews.

As we walked back, we met a lady who was crying and very agitated. She was the wife of the owner of a large, Jewish department store. It was the first time I had seen an adult cry. She said that the windows of their store were smashed, there had been looting, and the synagogue was set on fire. We then met an acquaintance who said that he would board a train to Berlin, and travel back and forth between Leipzig and Berlin until this blew over. My father told my mother he would do the same thing, but would first check whether my grandfather was all right and whether our knitted goods factory was damaged. He would call her from there. That call never came. Meanwhile, when we got back to our apartment building, my mother noticed that our nameplates had been removed, a preface to our pending eviction.

For the next 10 days, my mother tried frantically to locate my father. She eventually heard that he had been viciously beaten, transferred to a prison, and would soon be sent to the concentration camp Buchenwald, a place she had not heard of then. I cried every day he was away and asked my mother how God could let this happen. On the 10th day, my father was released. There were two reasons, apparently, why he was not shipped to Buchenwald like most of the other arrested men. First, demonstrating typical German legal fastidiousness, the Nazis needed him to sign some documents so that they could take over our factory. Second, my father had recently had a major operation for stomach cancer and had a large scar. The Nazis were afraid he might not survive the journey. Later, no one would have such scruples.

Following Kristallnacht, my parents realized that the Nazis’ noose around the Jews’ necks was tightening rapidly. They had already made plans to emigrate, but my escape now became their first priority. At this time the British government agreed to grant refuge to a limited number of children under age 17 years. A similar plan was introduced in Congress in the United States, but it died in committee. These so-called Kindertransports were permitted by the Nazis under conditions that the children had to come alone and could only bring one suitcase, no toys. Between November 1938 and August 1939, some 10,000 mostly Jewish children from Nazi Germany and Nazi-occupied territories reached England, thus escaping almost certain extermination. I do not know why I was fortunate enough to be included. Those of you with children can imagine the agonizing decision my parents made to send me, alone, to England, a little boy of 9, not knowing whether they would ever see me again. The children from the Kindertransports were billeted out to British families who had volunteered to take them. I was going to a family that my parents knew, though they had never met them: Bernard and Win Schlesinger.

Bernard was a London pediatrician and Win was the daughter of my grandfather’s cousin. They offered to take me into their home. They had five children ranging in age from 6 to 13 at that time. The oldest, John, would later become a famous film director, known for such pictures as Midnight Cowboy and Marathon Man. They also rescued 12 other Jewish children from Nazi Germany and Austria, and placed them into a hostel they established in London with a staff that furnished all the children’s financial, educational, social and religious needs. These 12 children, like me, literally owe their lives to this extraordinary couple.

I left Leipzig by train on March 15, 1939. When I said good-bye to my father that morning, my mother knew that I would never see him again as he was already mortally ill. He died only six weeks later. My mother traveled with me and several other children to a town in Westphalia to meet the rest of the Kindertransport and to deliver us, and our documents, to the authorities. From there on I was on my own, with a lot of other children, as we traveled to Holland and then by boat to Harwich in England, and by train to London. Win Schlesinger met me at the station and took me to her home. I spoke no English, but Win spoke a little German.

My mother and sister fled to Holland, and then to England on August 27, 1939, on the last KLM plane before the outbreak of war. I was one of the very fortunate few to be reunited with at least one parent. I lived with the Schlesingers but saw my mother and sister every few months.

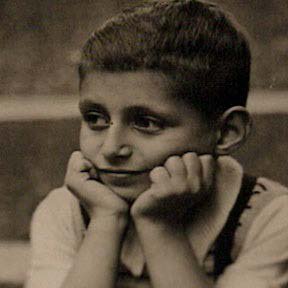

From the moment I arrived in England, I wanted to forget Germany, and I did everything possible to “become” English. It was a matter of survival in my boarding school, during the war with Germany, where the boys would not understand the difference between a German Jew and a German. I did not want to speak German, and so I forgot my native language almost entirely until, when I was about 13, I asked my mother to speak and write to me in German and, in that way, relearned the language.

The extraordinary journey I undertook last October came about because of the efforts of a relative in Berlin, Marianne Wintgen, whom I didn’t know as she was born after we left Germany. My mother had been very close to her parents and grandfather. Marianne had tried to locate me for several years, and her inquiry to a web site in Leipzig caught the attention of the staff of a German television program called Die Spuhr der Ahnen (Traces of Ancestors), which features stories about family ancestry. They, in turn, located me on the web, contacted me and offered to pay for me to come to Leipzig to make a film for their program. In this film I would meet Marianne and we would be taken to various sites in Leipzig that had played an important role in my life there, including a visit to my father’s grave. I would be interviewed about my experiences, such as those on Kristallnacht and the Kindertransport. My wife, Betty, was unable to accompany me, but our daughter, Karen, wanted very much to come along, and the TV network, Mittledeutscher Rundfunk (MDR), offered to pay for her also.

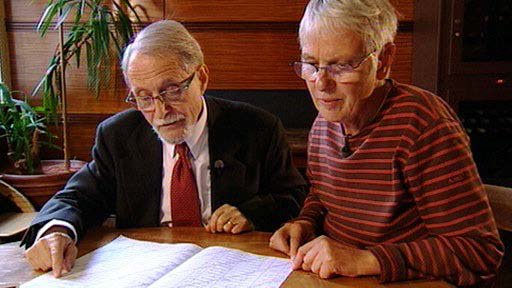

On October 3, Karen and I flew to Germany and were accommodated at a very fine hotel in Leipzig. We filmed for two days, beginning with my meeting with Marianne at the main railway station, my point of departure 70 years ago, and which I still remembered. Marianne had only been told the night before that I was alive and in Leipzig. I walked down the platform as though I had just arrived by train, and Marianne looked for me. She recognized me due to my likeness with my grandfather, whose pictures she had seen. We embraced warmly and immediately started a virtually non-stop conversation in German, as she speaks no English. We went to lunch with Annet Friedrich, the director of the film. There, in one of the many moving moments of the trip, Annet gave me copies of several documents she had procured: my father’s death certificate; a page from the police blotter from November 10, 1938, corroborating my father’s arrest; a document concerning the Nazi takeover of our factory (which ends with the salutation “Heil Hitler!”); and a notice from the secret police to auction a large batch of my mother’s books, listing her as “the Jewess Charlotte Sara Levy” (the Nazis required that the name Sara be added by all female Jews, and Israel by all male Jews).

Levy and Marianne Wintgen examining copy of police blotter recording his father’s imprisonment by the Nazis. (Photo credit: MDR)

We then went to our former apartment. It is currently used as a center for abused and disturbed children, and had been made accessible to the MDR. I still remembered some details of the apartment, and Annet’s questions reawakened more memories. After Kristallnacht in 1938 we were evicted as they no longer tolerated Jews. My mother had the almost impossible task of finding another home. My father was mortally ill. My mother had to look after me and my sister Elisabeth, who was less than a year old. She was preoccupied with trying to get us all out of Germany. Renting to Jews was forbidden. She finally found a small apartment to which we moved early in 1939, and the MDR crew also did some filming there.

We drove to our former knitted goods factory, which had been in the family since 1865. My father and grandfather had been the co-owners. It is now being renovated, but is still partly in ruins. We also went to the Old Jewish Cemetery, where my father is buried. Marianne and I were given a map of the cemetery and were filmed as we located our family plot. Seeing my father’s grave was a very moving experience for Karen and me, and I spent several minutes communing with him. The plot right next to ours had been desecrated with the words Juden Schweine (Jew pigs). In a filmed interview at the cemetery, I told Annet that it had taken me a long time to be able to talk to Germans without thinking about whether they, or their relatives, were Nazis who had murdered some of my family members or other Jews, but that I had eventually shed that feeling. She said that she is still tormented by questions whether any members of her family were involved in the Nazi atrocities.

Levy and Marianne Wintgen at his father’s grave, with members of the television film crew. (Photo credit: Nadine Oehls)

Annet had written to ask me whether I would be willing to be interviewed by some reporters and some children who had prepared a gift for me, and I had agreed. The interviews took place at the Jewish Cultural Center. We saw some exhibits there, and Marianne spotted photos of my grandfather. He became the president of the Jewish Community after the war, when only 16 of the 16,000 Jews who had lived in Leipzig remained. Remarkably, he had survived with his second wife, who was not Jewish, under harrowing conditions.

I was interviewed by two reporters. An article about this interview appeared in the Leipzig newspaper. They asked how I felt about being back in Leipzig and why I hadn’t come previously. Then came an especially moving event. Two teenage schoolboys, Julius and Paul, interviewed me. They had worked for the past months on a school project, researching my family and me. They conducted the interview in English and asked some excellent questions. They gave me a beautiful, illustrated, bound book that had been prepared by their teacher, containing the results of their research. The boys’ school project had consisted of reading the book and preparing an interview based on its contents. They also gave me a framed receipt from our factory, dated December 9, 1902, featuring the beautiful company logo. This was a remarkable event, one that inspires hope for the future of the German youth.

Karen and I then spent one day in Berlin, which neither of us had ever visited. We went to the Jewish Museum, designed by the Polish-born American architect Daniel Libeskind. Although we only saw part of it, we were most impressed. The tilting floors and the skewed angles at which the walls meet deliberately convey an appropriately disturbing sense of disorientation. We were deeply moved by the numerous displays about the fate of Jewish individuals and families, enabling one to relate personally to these events. We also visited the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, consisting of some 2,700 concrete slabs. It was jarring to be brought back so vividly to the horrors of the Nazi era after a much more healing time in Leipzig, but a most worthwhile experience.

Karen had to return to the States, but I spent three days in London, visiting friends and relatives. Among them were Walter Weg and his sister Renate Daus, two old school friends from Leipzig who live in London. We spent a wonderful afternoon reminiscing about Leipzig. I told Walter and Renate the following story about their father, which they had never heard and which my mother recounts in her memoirs. After my father died, my mother worked feverishly to escape from Germany with my sister. The Nazis had seized her passport and refused to return it. The officials at the passport office denied having it, but my mother saw it, as it had a noticeable ink stain. She was in despair whether she would ever get it back, when she remembered my father telling her about a man at our factory who, he thought, could be bribed. My mother had never in her life bribed anyone, but she was desperate, and so she took the courageous step to approach him to see if he could get her passport. He agreed and told her the price. By that time, the Nazis had confiscated all the Jews’ money, merely providing them with weekly subsistence allowances. How could she get the money under these strict Nazi fiscal policies? It happened through an extraordinary twist of fate a few weeks earlier. My mother had to sort through our belongings in preparation to pack them. Renate and Walter’s father, Fritz Weg, offered to help her. When my mother came across my father’s wallet, Mr. Weg suggested that she look inside. To her astonishment she discovered 700 marks there. Having money after the Nazi confiscation constituted an extremely serious offense that might have cost her life. She couldn’t imagine why my father had left so much money in his wallet, but then she remembered that shortly after his last business trip abroad, he had to have some surgery, and while he was being anesthetized he mumbled something about money in a wallet. She now realized that this money must have been left after his business trip, and that he had forgotten to hand it over to the authorities. This became the money, then, that she used to pay the bribe, and that is how she got her passport back. Mr. Weg had probably saved her life.

That evening, I met Hilary Schlesinger. She is the sole survivor of the family who took me into their home when I arrived on the Kindertransport, and with whom I stayed for seven years. I have been in frequent, close contact with the family ever since, but had not seen Hilary in 10 years. My arrival coincided with her 80th birthday, and since my 80th was just two weeks later, we decided to have dinner together to celebrate. It was a memorable evening of reminiscing and reconnecting.

On my return flight to Washington, I sat next to a man who told me that his maternal grandparents were German Jews who had left at the same time as I did. His paternal grandparents were German Catholics, and he feels sure that this family included Nazis. He has a master’s degree in international law from Harvard and also does pro bono work to help individuals and institutions gain restitution for war-related crimes. This interest arose after he served in the U.S. army in Bosnia and saw the horrors there. This encounter seemed like a fitting conclusion to my journey.

The film, entitled “The Little Boy and the Nazis”, was shown on German television on November 25, 2009. I was provided a link to view it before it was aired. It is a skillful mix of Marianne’s search for me; our visit to various locations in Leipzig which served as backdrops to the interviews of me; scenes from my childhood, recreated by actors depicting my parents and me; family photographs; and historical footage of Kristallnacht, the Kindertransport, and Leipzig during the 1930s, including the anti-Semitic signs that were displayed throughout the city. I participated in a chat room after the film. I had never been in a chat room before, let alone one conducted in German on such an emotional subject. There were dozens of participants in the one-hour chat. I was astonished at their reaction. Many viewers were deeply moved. They asked about my feelings at returning to Germany, and many expressed their admiration that I did so. The father of the child actor who played me as a boy wrote that this was a great honor for him. Perhaps my statement about the necessity of letting go of anger and bitterness struck a chord. Obviously, my experiences were not exceptional, and they were trivial compared to those of countless other children, most of whom never lived to tell their tale. Mine had a happy outcome, which may have made it easier for people to relate to. Marianne, who participated in the film with me, thought that it makes a statement against prejudice of all kinds. If so, I am most gratified.

Several things contributed to making this journey such a positive experience for me. Karen’s presence meant a great deal. She was supportive and helpful, taking care of practical details, and she kept me emotionally grounded. She was moved by our experiences and was very involved in the whole venture. We shared a unique father-daughter experience. Our warm interactions with the MDR crew also contributed. Every one of them was kind and thoughtful, sensitive to the tenor of the whole event and very respectful of my feelings. We bonded during the interviews, some of which evoked deep emotions in me, and they were drawn into my story. Annet Friedrich, the director of the film, cried on several occasions. All this facilitated my openness with them and contributed, I believe, to the fact that the event was so powerful. Finally, I met Marianne, whose quest for reconnection precipitated this journey, and with whom I have established a warm relationship.

I was struck by the frequent reminders we saw of Germany’s role in the Holocaust. In the book the boys gave me there is a section that deals with events in Leipzig commemorating Kristallnacht. We saw many classes of schoolchildren being taken to the Jewish Museum and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews. Marianne told us that all schoolchildren from East Germany were required to visit a concentration camp. This made me think that we have nothing comparable in the United States to deal with the horror of slavery and the post-slavery period, and that, were we to do so, it might help us to deal with our continuing problems concerning race.

Reliving my experiences from seven decades ago emphasized how incredibly fortunate I was. I have never forgotten that I owe this to my parents’ courage, the Schlesingers’ generosity, the love of both families, and the British government’s decision to make the Kindertransports possible. They saved my life and laid the foundation for my future happiness. This journey, which I never considered taking until I was invited to do so, was an extraordinary event in my life, something that came unsought and that has profoundly affected me. All those connections to the past lay dormant inside me, and although I have spoken about many of them before, I never relived them. Some painful memories were revived, but some healing took place – healing I didn’t know I needed. It reinforced for me the importance of letting go of past horrors, a process that began some years ago and that was greatly strengthened by this voyage.