Teaching Plastics to “Speak”

Chemist Davoud Mozhdehi is working on an autonomous synthetic material that could create what he calls “smart plastics.”

According to notreallyexpired.com, 40% of the food produced in the United States goes uneaten each year, resulting in 160 billion pounds of wasted food. At the same time, 37 million Americans struggle with hunger, according to feedingamerica.org. A new kind of plastic could be part of the solution to the problem of food waste.

Much of that waste is due to confusion over the sell-by and use-by date labels and whether or not food is actually expired. Imagine having a milk container programmed to analyze its contents and alert the consumer that the milk is spoiled. Such a product could eliminate the need for the smell test and our uncertainties about the use-by date stamped on packaging and ensure that the milk we are consuming is safe to drink.

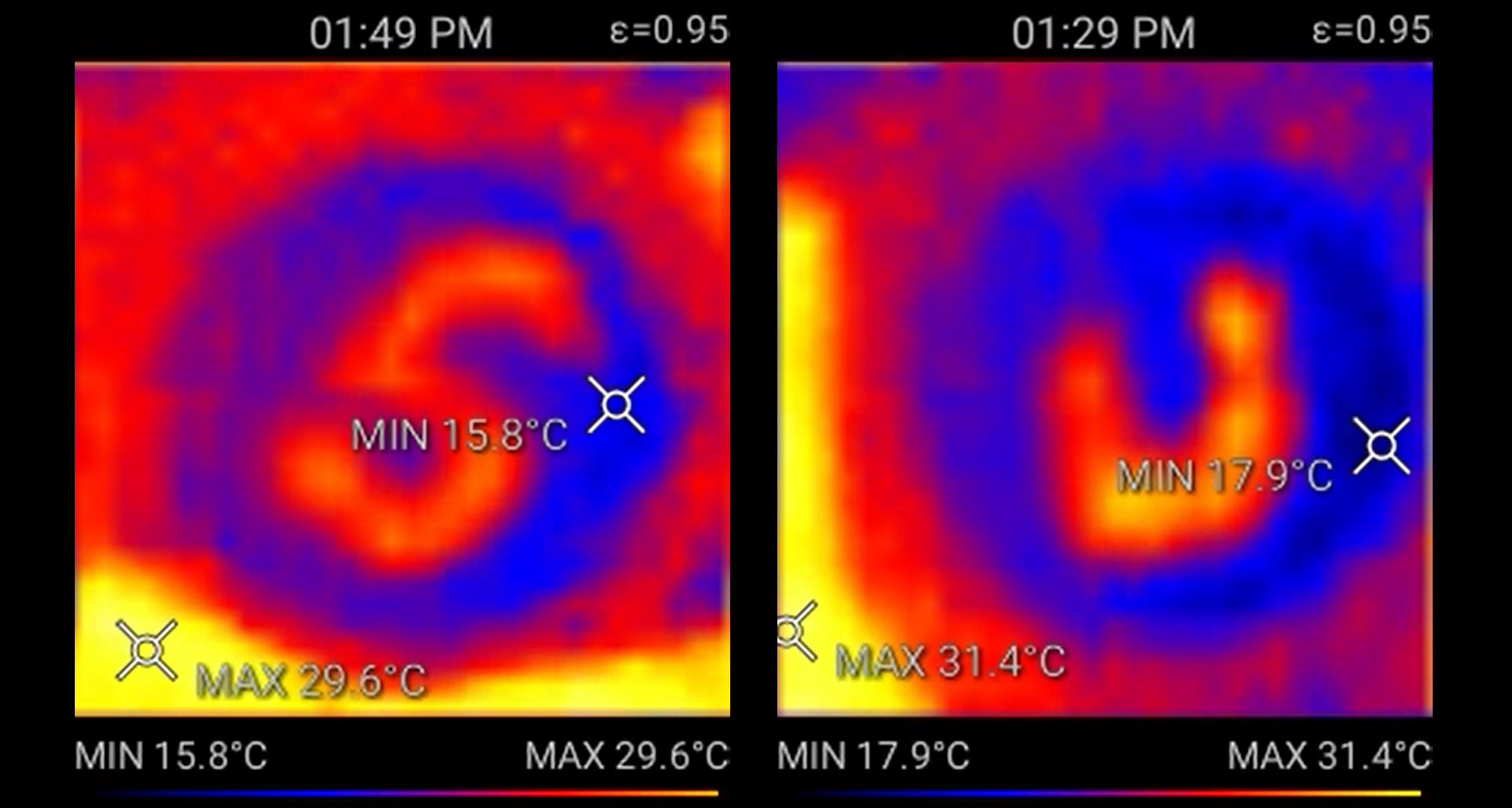

To make this vision a reality, researchers in Assistant Professor of Chemistry Davoud Mozhdehi’s lab are working to develop a new form of synthetic polymer that can consume fuel (i.e., the potentially spoiled food), change after eating and emit a visual signal. Similar to the way the human body produces heat after eating food, these new synthetic polymers, known as Thermally Energized Self-Regulating Materials System (ThERMoS), will generate heat after consuming energy. The heat generated would then create a visual cue for the consumer.

Mozhdehi captured photographic proof of the process on a petri dish with an infrared camera. The image shows a polymer emitting heat after consuming chemical fuel, shown by a reddish-orange color.

Plastics were created to take the place of metal and glass, both static materials. Mozhdehi and his team are essentially training plastics to act in a much different manner—interacting with their environment and converting chemical energy into usable feedback.

“Our goal is to make plastics that make a decision by using the energy acquired from eating,” says Mozhdehi. “This is a profound transformation in the use and properties of plastics.”

In the case of the spoiled milk, when bacteria begin to grow, the trained plastic would change color to alert the consumer that it is no longer safe to drink. In time, the response generated from this kind of smart plastic interaction could make use-by and sell-by dates much more accurate, reassuring consumers that there is no need to discard that unopened package, and no need to add to the food waste crisis.

Although it may be years until this technology is viable on the consumer level, thanks to Mozhdehi’s research and others in BioInspired Syracuse: Institute for Material and Living Systems, what sounds like science fiction may someday be a reality.

Mozhdehi’s research is being funded through a grant from the American Chemical Society’s Petroleum Research Fund (PRF). PRF grants are awarded to fundamental research in the petroleum field. Since most plastics are derived from petroleum, research that could advance polymer technology is supported by the PRF.