Art of Resistance and Resilience

While researching early 20th century Pueblo painters, Sascha Scott seeks to decolonize academic processes

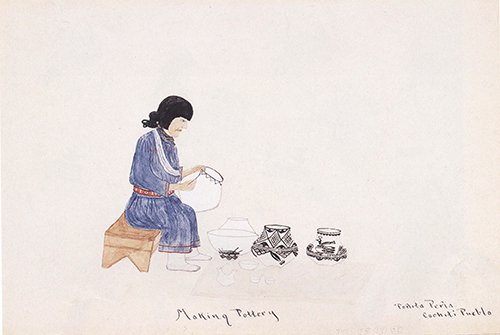

When looking at the paintings by Pueblo artist Tonita at a museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, art historian Sascha Scott met with Peña’s great-granddaughter. Scott learned that the genealogy presented in many accounts of Peña and her family are incorrect. Getting the facts straight is one of the many reasons she meets with tribal liaisons and relatives of the early 20th century Pueblo artists she is writing about. Doing so also provides important insights into the artwork.

“For outsiders, the paintings of dances I write about can seem static,” Scott says. “For Pueblo people who participate in the sacred ceremonials, seeing these paintings call to mind the singing, drumming, dancing and sense of community that are integral to their meaning and importance for Pueblo peoples.”

Thanks to a $6,000 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) summer stipend, Scott will spend two months in Santa Fe this summer continuing that work. She’ll visit museums and archives and meet with people connected to artists as she researches her second book, “Modern Pueblo Painting: Art, Colonization, and Aesthetic Agency.”

“Consultation and dialogue with Pueblo communities is an integral part of my work. This process is more successful when I am in New Mexico because we can meet in person and often in front of the artworks,” she says. Santa Fe is also close to primary source material that is central to her research, including the collection of Indian Arts Research Center at the School for Advanced Research, where she was a summer fellow in 2011, and the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

Her book will include a discussion of five Pueblo artists, through which she examines the aesthetics and politics of early 20th-century Pueblo art. She’ll explore the artists’ relationships to their home communities, their complex engagement with dominant structures, and how they navigated colonial politics and markets.

Hers is one of 65 2018 NEH grants totaling $390,000 that support full-time scholarly work for two months. Scott also received a Howard Fellowship, awarded by the George A. and Eliza Gardner Howard Foundation through Brown University, to support a research leave for academic year 2018-19. She is one of eight Howard Fellowship recipients representing the fields of history of art and architecture and sculpture. Scott began work on this project as a faculty fellow at the Humanities Center this year.

In addition to Scott’s summer stipend, two Syracuse University projects also received 2018 NEH awards.

“Sascha Scott’s research on Pueblo artists arrives at a very important historical moment when the relationship between indigenous artists and colonial systems of patronage and power are being challenged, scrutinized and dismantled,” says Romita Ray, chair of the Art and Music Histories Department. “The NEH summer stipend recognizes just how valuable her contribution will be to the history of art.”

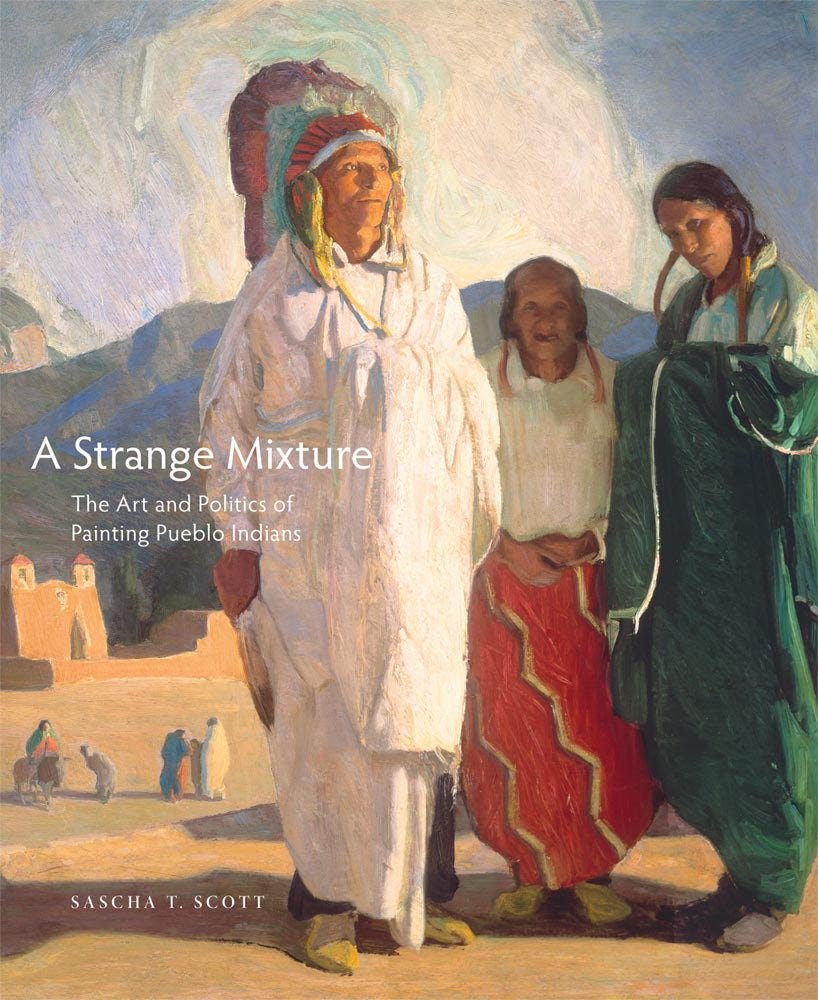

Scott’s first book, “A Strange Mixture: The Art and Politics of Painting Pueblo Indians” (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), largely focuses on the representation of Pueblo peoples by white artists, but includes one chapter about San Ildefonso Pueblo artist Awa Tsireh. “When writing this book, I knew the story had to include Pueblo peoples’ self-representation–how they depict themselves as a counternarrative of how white people imagined them,” she says. As she wrote about Awa Tsireh, she also knew she would devote her next book project entirely to him and his peers.

Her work provides insights into the history of the Northern Pueblo, who comprise 19 communities in New Mexico. “They still live on their ancestral lands. But these lands have been infringed upon by American colonization, which eroded their access to land and water. As a result, their traditional subsistence structures were also eroded, which led them to create objects for tourist and art markets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” she says.

Their paintings–typically of daily life, ceremonial dances and animals depicted with no backgrounds–developed from contact with anthropologists and government school teachers. “The genre formed due to contact with outsiders,” Scott explains, “and then flourished because it was highly valued and promoted by American cultural modernists in New Mexico. Modernists helped to create a national market and audience for Pueblo art.” She continues, “Some of America’s most well-known modernists traveled to the Southwest with the outbreak of World War I since they couldn’t go abroad. New Mexico became a hot spot because of its spectacular landscape, but also because it seemed culturally different.”

Scott challenges the dominant narrative that Pueblo artists painted what the white market wanted. “Even as their political and economic agency was under attack, they had the ultimate control over what they paint and why,” she says. “Outsiders thought they were getting an insider view via pictures of ceremonial dances. But most Pueblo artists were showing what was already public. They were painting dances that, although sacred, were open to outsiders and popular among tourists. The artists were carefully guarding their esoteric cultural practices.”

The work “is an art of resistance,” she says. The government at the time was suppressing dances and other Pueblo cultural practices, and separating children from families and sending them to boarding schools. “Even as Pueblo artists struggled with oppression from dominant structures,” she says, “they manage to carve out places of resistance and resilience.”

Before she decides on what she will write about, she approaches the artists’ descendants and communities as consultants: “I say, ‘Here’s the project. Here’s a range of images. Is there anything you don’t want me to represent?’ If they say ‘no’ to a painting or topic, I respect that decision. I ask consultants to read my work and for feedback before I publish.”

Scott insists this process does not limit her academic freedom. “I’m part of a scholarly movement that is aiming to ‘decolonize’ academic practices—that is, working with communities and respecting their needs instead of imposing my needs on them,” she says. “I find this approach more positive than limiting.”

In addition to highlighting transcultural indigenous art, her book aims at a broader message. “This work is intimately connected to the struggle indigenous peoples face today, from continued infringements on their lands, to cultural oppression and appropriation, to misrepresentations of their histories and their invisibly in the present, to overt racism,” she says. “Their resilience and resistance continue.”