Purple Reign

Late musician’s commitment to social justice overlooked, James Gordon Williams says

James Gordon Williams first heard Prince’s music as a high school student. “The album Sign 'O' the Times (1987) was popular then and Prince’s music videos were available via MTV-style music video channels,” recalls Williams, assistant professor of African American Studies at the College of Arts and Sciences. “I also had a cursory awareness of “Purple Rain,” but did not grasp the cultural significance of the landmark album and the subsequent movie at that time,” he adds.

Williams is a critical musicologist, composer, improviser and pianist whose research focuses on understanding how African-American musical activist texts connect with what the late eminent scholar Cedric Robinson called the Black Radical Tradition.

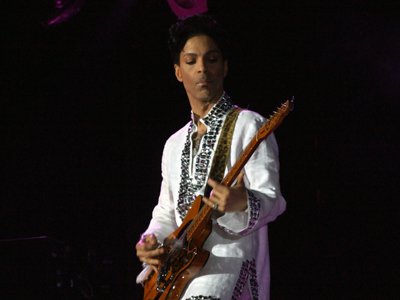

Williams saw Prince perform live twice. The second performance was the May 10, 2015, Rally 4 Peace concert in Baltimore. The concert was dedicated to healing Baltimore and supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, the ongoing international debate over the way the police treat people of color.

At the Baltimore concert–a year before he died–Prince released “Baltimore,” a protest song dedicated to Freddie Gray, a song Williams contends was a critique of the system that leads to this type of incidents. “Baltimore” is linked to what Williams describes as Prince’s “covert, but avid, support of social justice initiatives that support black humanity.” His essay, “Black Muse 4 U: Liminality, Self-Determination and Racial Uplift in the Music of Prince” was published in the September 2017 Journal of African American Studies, a special issue that focuses on the life of Prince Rogers Nelson. The academic journal presents the first scholarly collection of articles on Prince.

“Though Prince is considered a popular musician by many people, his music disregarded genre and has layers of depth that require deep study,” Williams says. “No two Prince compositions are the same and his songwriting craft never stopped developing due to his work ethic and insatiable appetite for creative practice.” The essay “was an opportunity to articulate ideas about his music in a way that I could not have done 30 years ago.”

In May 2017, Williams presented a paper at “Purple Reign: An Interdisciplinary Conference on the Life and Legacy of Prince” at the University of Salford in Manchester, England.

Scholarly articles written about Prince after his death will be markedly different than scholarship written when he was alive, Williams says. “Various devotees read Prince in a plethora of ways which have to do with culture, world geography, sexuality and many other factors. Yet much of the critical scholarship on Prince before his passing discussed his work in culturally ambiguous terms. The historical evidence tells us that black musicians like Prince were invested in helping the core community that supports them.”