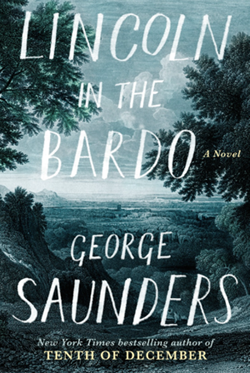

George Saunders’ First Novel, ‘Lincoln in the Bardo,’ Debuts at No. 1 on New York Times Bestseller List

Saunders is currently in the midst of an international, multi-city book tour

For an author, you are truly in an enviable position when fans and book critics alike anxiously await your next creation. So it is for College of Arts and Sciences’ English professor George Saunders. Especially now, with the publication of the acclaimed short-story writer’s long-awaited first novel, “Lincoln in the Bardo” (Random House, 2017), which hit bookstore shelves and online retailers last week and has debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times Bestseller List.

The “Bardo” in the title refers to a Tibetan word for a transitional zone—think spiritual waystation or limbo—where the soul goes between a person’s death and reincarnation. In this instance, the bardo is set in a Georgetown cemetery. Or rather in a gauzy netherworld anchored to that graveyard—a place populated by unsettled spirits, where much of the book’s story unfolds over the course of a single night in late February 1862.

The book’s premise stems from an anecdote Saunders heard some 20 years ago, about President Abraham Lincoln visiting the crypt of his 11-year-old son, Willie, lifting the recently deceased child from his coffin, or “sick-box,” and lovingly cradling and speaking to the boy. “That story just stuck with me. I just couldn’t shake it,” Saunders says. He began casually reading up on Lincoln and the Civil War while pursuing other writing projects, including magazine articles and a string of highly successful short story collections.

Then, in fall 2012, just before his stellar “Tenth of December” came out, Saunders finally committed to pursuing the Lincoln project and developing a story based on the historical footnote. “Before that, I’d felt I didn’t have the skill for such earnest material, but then I thought, basically: ‘If not now, when? And I felt that it might be a talent- and vision-expanding thing to try, even if it ultimately failed. And that’s really the point of being engaged in art anyway—to make oneself bigger.”

For his research, Saunders began drawing from books on Lincoln and the vast Civil War holdings in Syracuse’s E.S. Bird Library. “Reading historical stuff became a sort of side-hobby for me—at night, on planes,” Saunders says. “It was made a little easier because I usually knew what I was looking for—what particular events. Also, as things progressed, I allowed myself to invent fictional historical texts, to try to tell the higher (highest) artistic truth.”

It took Saunders about four years to complete “Bardo.” In between start and finish came the publication of “Tenth of December” (Random House, 2013), a short-story collection that The New York Times hailed as “the best book you’ll read this year”—a heady endorsement, especially given it came at the very beginning of that year: in the Jan. 3, 2013, issue of The New York Times Magazine.

And on May 11 of that same year, Saunders delivered his memorable convocation address to College of Arts and Sciences graduates in the Carrier Dome. The New York Times posted the transcript on its website a couple months later, and the speech quickly went viral—within days it was viewed more than one million times. It inspired an animated short voiced by Saunders. And the following spring, his moving essay on kindness was published in book form—“Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness” (Random House, 2014)—and became a bestseller.

More recently, Saunders was a finalist for a 2017 National Magazine Award (his seventh nomination; he has won four times) in the Feature Writing category for his article “Who Are All These Trump Supporters” in the July 11/18, 2016, issue of The New Yorker.

“Bardo” is a story of love, profound sorrow and, for at least some of the souls/characters, redemption. Throughout the book, Saunders employs real historical quotes along with his own fictional anecdotes. For instance, an observer’s description of Willie:

“I was one day passing the White House, when he was outside with a play-fellow on the sidewalk. Mr. Seward drove in, with Prince Napoleon and two of his suite in the carriage; and, in a mock-heroic way—terms of intimacy evidently existed between the boy and the Secretary—the official gentleman took off his hat, and the Napoleon did the same, all making the young Prince President a ceremonial salute. Not a bit staggered with the homage, Willie drew himself up to his full height, took off his little cap with graceful self-possession, and bowed down formally to the ground, like a little ambassador.”

Saunders interweaves these short passages with the voices of his created characters, all written in a period-appropriate style—each differentiated by text that reflects varying levels of the characters’ literacy, upbringing and earthly lives. “When we ‘hear’ these dead people, we are actually seeing the way that, in life, they ‘wrote,” Saunders says. “So one person spells poorly, one uses a high number of ampersands, etc.”

An example, Mr. Maxwell Boise, reflecting on the moment of his demise:

“Take the money, I said. I am calm.

You will also, sir, please, remain calm, I said. We have no enmity between us of which I am aware. Let us regard this as a simple business transaction. I will hand you my wallet, just so, and then, with your permission, be one my—

No, no, no.

No no no.

Entirely the wrong & illogical thing for you to—

Low stars, blurred rooftops.

& I am punc tured.”

In total, 166 voices are heard, guiding the story along in short sequences that are at the same time dizzying and enthralling. Along with Willie and President Lincoln, three main characters are at the forefront: Hans Vollman, a gentleman nearly three decades older than his teen bride, killed by a fallen beam on the day they had finally agreed to consummate their marriage; Roger Bevins III, a young gay man who slit his wrists in response to unrequited love and now manifests in a blurry, disquieting form with multiple eyes, noses and hands; and the Rev. Everly Thomas, his face frozen in a perpetual scream.

In the bardo, they befriend Willie, helping the lad deal with his new form of existence and entreating him to move on, for “young ones are not meant to tarry.” By virtue of their youth, the young have accumulated few life regrets and so should have an easier time in, essentially, putting their bags in order and ascending. But children who linger in the bardo—like Willie, who maintains a tenuous tether to his previous existence by way of his father’s frequent gravesite visits—are at risk, their souls depleting the longer they stay.

Saunders sets the book’s scenes in lush detail. An early one unfolds at the White House, on the night of a grand reception hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln and attended by more than a thousand guests:

“The flowing sugar gown of Lady Liberty descended like drapery upon a Chinese pagoda, inside of which, in a pond of candy floss, swam miniature fish of chocolate. Nearby, lusty angels of cake waved away bees hung aloft on the thinnest strings of glaze.” – Wickett, op. cit.

“They dined on tender pheasant, fat partridge, venison steaks, and Virginia hams; they battened upon canvasback ducks and fresh turkeys, and thousands of tidewater oysters shucked an hour since and iced, slurped raw, scalloped in butter and crackermeal, or stewed in milk.” – Epstein, op. cit.

“Yet there was no joy in the evening for the mechanically smiling hostess and her husband. They kept climbing the stairs to see how Willie was, and he was not doing well at all.” – Kundhardt and Kunhardt, op. cit.

Another, more profound scene unfolds not long after. Willie, having succumbed to typhoid fever, has been lain to rest in the crypt. His father visits, to the amazement of the assembled ghosts.

“The man bent, lifted the tiny form from the box, and, with surprising grace for one so ill-made, sat all at once on the floor, gathering it into his lap.” – Roger Bevins III

“Sinking his head into the place between chin and neck, the gentleman sobbed, raggedly at first, then unreservedly, giving full vent to his emotions.” – the Rev. Everly Thomas

It is an agonizing scene, with the very profound personal grief of Lincoln, the father, set amidst the anguish of Lincoln, the leader, suffering the emotional toil of guiding his country through the early days of a civil war going badly.

Saunders says he hopes readers will be affected by what they read: “I just hope they are moved in some way. I think of writing as a sort of theme park ride—the idea is to alter the reader in some non-trivial way. For this book especially, I really want people to be emotionally jangled.

“At this stage of my life, the thing I really want to do is have the book make some energy—cause something, anything, in the larger culture,” Saunders says. “And I am happy about the timing, given the rise of Trump. This feels like a good time to think about what greatness looks like in a leader (Lincoln), and to turn the mind toward what America is really all about.”

For those who prefer to listen to books, “Bardo” is also available in the form of an audiobook (seven hours, 25 minutes) with an impressive 166-person voice cast that features Saunders as Rev. Thomas, actor Nick Offerman as Vollman, humorist David Sedaris as Bevins III. Also included are Saunders’ parents, wife, sisters and daughters; fellow author and SU professor Mary Karr; and a bevy of actors and comedians, including Don Cheadle, Kat Dennings, Lena Dunham, Bill Hader, Keegan-Michael Key, Megan Mullally, Julianne Moore, Susan Sarandon, Ben Stiller, Jeffrey Tambor, Bradley Whitford and Rainn Wilson. Recording occurred over four months in 17 different studios.

There is also a short virtual reality film based upon the early crypt scene. The 10-minute production written and directed by Graham Sack is available for iPhone and Android devices and can also be seen on YouTube and on The New York Times VR platform.

Saunders is currently in the midst of a stamina-sapping, multi-city book tour that includes stops in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Miami, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., as well as abroad in Dublin, London and Paris, among other locations. Plus he is doing interviews: with Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers and Scott Simon.

What’s next for the author? “I have no idea,” he says. “I’ve been working on an adaptation of my short story ‘Sea Oak’ for Amazon, but other than that I am just waiting for the well to refill, so to speak.” Until then, Saunders lovers have “Bardo” to sate their thirst.