On Borrowed Time

Despite calls for divestment, completion of DAPL signals new chapter in Standing Rock conflict

When Norway’s largest private investor recently pulled out of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), the news barely made a blip on the world’s radar. For Phil Arnold, director of the Skä•noñh-Great Law of Peace Center in Syracuse, the message was loud and clear: “People who know about investing are finally realizing there is no future in fossil fuels and in their spinoff industries, such as pipelines. Standing Rock has brought home the need to distance ourselves from life-killing technologies as quickly as possible.”

As professor and chair of religion in the College of Arts and Sciences, Arnold also heads up an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grant project that combines scientific and Native American knowledge to promote environmental stewardship. Nowhere is there a greater need for such synergy, he believes, than in North Dakota, where the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes continue to battle the routing of a $3.8 billion, 1,172-mile-long pipeline past the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

“Drilling is complete, but companies are starting to see DAPL as a poor, long-term investment, economically and environmentally,” he says. “There’s too much uncertainty in the project.”

The Norwegian investor in question, Storebrand, is a 250-year-old juggernaut specializing in sustainable, socially conscious projects. On March 1, the Oslo-based company announced it had sold off nearly $35 million worth of shares in Phillips 66, Marathon Petroleum Corp. and Enbridge—North American co-owners of DAPL.

Storebrand’s decision to divest is the latest blow to the hotly contested pipeline, whose completion in southern North Dakota could imperil local drinking water and sacred burial grounds. Since Feb. 7, when the Army Corps of Engineers granted an easement to finish DAPL (allowing the pipeline to go under the Missouri River at Lake Oahe, near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation), a growing number of entities have withdrawn funds from Wells Fargo and other banks financing the project. They range from individual account holders to the city councils of Seattle, Washington, and Davis, California. As of this writing, activist Jackie Fielder is persuading San Francisco to divest, and New York City has put DAPL banks on notice.

Brian Patterson, a Bear Clan representative to the Oneida Indian Nation’s governing body, is not surprised by the turn of events. “We have awakened a sleeping dog to full alert and to positive action around the globe,” says Patterson, past president of United South and Eastern Tribes, representing 26 indigenous nations east of the Mississippi River. “That sleeping dog is not only our allies, but also the corporations that realize oil is a diminishing resource. We must creatively diversify to foster a more economically viable and sustainable future.”

Patterson admits that, despite recent progress at Standing Rock, the conflict is symptomatic of a larger problem rooted in racism and indigenous oppression. He points to a series of religious documents known as the Doctrine of Discovery that, for more than 500 years, has justified the colonization of the Americas and the oppression of its Native peoples.

“More needs to happen [at Standing Rock] that requires actions and alliances,” Patterson says. “This is not a time to be timid. We are qualified for this moment, and we must take action for the well-being of our planet.”

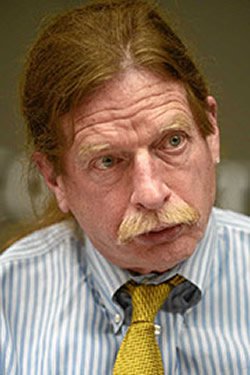

Joe Heath ’68, general counsel for the Onondaga Nation and a Syracuse-based New York state attorney, says divestiture is one way to block the “pipeline boom.” He praises his alma mater for dropping fossil fuel stocks from its endowment, but implores the University to do one better. “Syracuse needs to dump the 17 banks affiliated with DAPL,” says Heath, who credits his career path to a constitutional law course taught by the late Maxwell professor Michael Sawyer. “It would really shift public opinion and influence lawmakers.”

Heath considers Standing Rock the latest in a string of broken promises between the United States and indigenous nations, stemming from the Doctrine of Discovery. He reserves his harshest criticism for President Trump and his “robber barons.” “Everything that has happened since Dec. 4, with the halting of the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, to Trump’s swift granting of the easement to drill under Lake Oahe, is part of the government’s phony trust doctrine,” says Heath, who also condemns Trump’s attempts to dismantle Obama-era EPA regulations. “The privatization going on now with Indian land is just allotment all over again. [Allotment was a national policy between 1887-1934 in which the U.S. government divided Indian tribal land into allotments for individual Indians and families. Most of the land—approximately 90 million acres’ worth—was appropriated by white settlers and business interests.] Such privatization leads to massive oil, gas, coal and uranium exploitation—an aging industry that, like the rest of us, is living on borrowed time.”

Melissa Etheridge knows a thing or two about borrowed time. A breast cancer survivor, she is one of the Sioux’s most beloved, high-profile supporters. In February, Etheridge brought her band to Turning Stone Resort Casino, about 30 miles east of Syracuse, to raise legal defense funds for people detained or harassed during the Standing Rock conflict.

The concert was presented by the Oneida Indian Nation, with support from the Standing Rock Sioux, and came on the heels of Trump’s executive order to advance construction of DAPL under “terms and conditions to be negotiated.”

“These are very, very dark days,” says the Grammy Award-winning singer, speaking by phone from her home in Southern California. “Once again, we find ourselves under a president who values money above everything else. It is a very 20th-century state of mind. We elected oil and gas, even though they are finite resources, and we have spent the past 20 to 30 years developing alternatives. This is the last hurrah for the fossil fuel industry, and Standing Rock is the epicenter of that.”

Environmental issues always have been important to Etheridge, but it was not until after her 2005 battle with cancer that they took on added significance. “Breast cancer made me realize that I needed to take care of my inner body, while being a steward of my outer world. Both are closely related,” says Etheridge, who is part of a growing list of musicians, including Neil Young, Jackson Browne and Dave Matthews, involved in the fight at Standing Rock. “It’s my job as a human being to protect the things that come from the Earth, such as clean water and healthy food. I believe we can reverse all this and get back on the track of sanity, moving toward alternative energies and a cleaner, better life. That’s what Standing Rock will be remembered for.”

Etheridge echoes what is on the minds of many “water protectors” (as Standing Rock supporters are called)—that, for all of Trump’s perceived business acumen, his decision to focus on gas and oil and to revive the ailing coal industry is outmoded.

Joe Heath, who spoke at Etheridge’s concert, thinks Trump is on the wrong side of history. “It’s not just him, but it seems like his whole cabinet is out of touch and ill-informed,” he says, citing the president’s intentions to cut EPA R&D spending by more than 40 percent. “Report after report shows that renewable energy employment exceeds that of fossil fuel-based industries. For instance, solar electricity generation now employs more people than the electricity generation of coal, oil and natural gas combined. Jobs in fossil fuel extraction and services have declined by more than 4 percent annually since 2012. Wind and solar jobs exist in every state—something that could benefit Central New York and the Rust Belt, in general.”

Regardless, construction of DAPL remains on schedule, with oil expected to flow in mid-March. (When completed, the pipeline will pump 470,000 barrels of crude a day from North Dakota to Illinois.) Trump also is resurrecting the Keystone XL pipeline, a 1,200-mile project that Obama rejected in 2015. Should Keystone ever get off the ground, it will shift more than 800,000 barrels daily from the Canadian oil sands to refineries in the Gulf Coast.

Indeed, DAPL and Keystone are ambitious projects, but, compared to the 2.5 million miles of U.S. pipelines already in existence, they are a “drop in the bucket,” writes David Zeiler in The Wall Street Examiner. One study reveals that, from 2013 to 2015, the United States added more than 12,000 miles of crude oil pipelines—presumably while nobody was looking.

“Most people don’t even know that pipelines get created all the time,” Heath says. “But there’s a lot we can do, using popular support to turn the tide and affect change. We did it with fracking [which New York State prohibited in 2015], and we can do it again with the Dakota Access Pipeline. If investor confidence continues to erode, the project could become financially disadvantageous, and more lending institutions would pull out.”

Leave it to Etheridge, also a well-known medical marijuana advocate, to end on a, uh, high note. “I’m not one to meet crazy with crazy, but, if I had a chance to sit down with Trump, I’d tell him that Standing Rock is about spirit, about reality,” she chortles. “I would say, ‘Donald, try choosing the opposite of fear. Let’s have a smoke, and talk about it.’”

Standing Rock is proof that Christianity is in crisis. At least, that is what Phil Arnold thinks. “Every piece of property bought or sold in the United States, including the territories of our original nations, is based on the Doctrine of Discovery,” he says. “Only Indians cannot own land. They are unable to build equity. That is why Native American reservations are among the poorest communities in the country. As long as they are denied the right to control their resources, they will be locked into poverty and federal dependence.”

Arnold is part of a growing cadre of scholars to denounce Christian jurisdiction over indigenous lands and peoples. It is something, he says, that began in 1493, when Pope Alexander VI unveiled the Doctrine of Discovery to condone the enslavement or killing of people who would not convert to Christianity. Divine Law also gave Christian explorers—and, later, U.S. land speculators—permission to discover, claim and exploit indigenous territories.

“Pope Alexander’s so-called ‘Christian Empire’ morphed into the American Empire, and became the framework for the kind of domination that persists to this day, with President Trump and the Army Corps of Engineers,” Arnold says. “It’s this intertwining of Christianity and American imperialism—using acquired jurisdiction to take over the lands of heathens and infidels, as the Justice Department once put it—that defines Standing Rock.”

David Archambault II, chair of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, echoed these sentiments during a recent visit to Cornell University. Since Texas-based Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) first announced plans to build DAPL in 2014, Archambault has crisscrossed the globe, garnering opposition to the project. Much of his case rests on two treaties, recognizing Sioux national sovereignty, which the United States has violated repeatedly for more than 150 years.

“We knew our chances were not good,” Archambault told a packed room when he brought up his request for an injunction to halt DAPL’s construction last fall. “Throughout history, federal courts have never sided with tribes. The deck was stacked against us.”

Archambault recalls how Trump ordered an expedited review of DAPL on his fourth day in office. The fait accompli came two weeks later, when Robert Speer, acting secretary of the Army, gave ETP the “green light” to finish the project. Archambault was on his way to a meeting with William Kirkland, deputy director of intergovernmental affairs at the White House, when he got the devastating news.

“I felt slighted because I had been promised a meeting with William Kirkland, before the Army Corps of Engineers said they would make a decision,” he recalls. With the stroke of a pen, Speer canceled a much-anticipated environmental impact study of DAPL and granted an easement for ETP to drill under Lake Oahe. He also suspended the customary 14-day waiting period following his order, enabling ETP to resume work immediately. “I felt like I had been set up,” Archambault adds.

Today, the scene at Standing Rock is vastly different from the one two months ago. Gone are the students, activists and tribal allies, whose ranks swelled to more than 10,000, dotting the landscape with tents, teepees and campers. In their wake is a small, quiet band of supporters—200, at last count—making the best of dwindling resources and pools of snowmelt.

Reports have surfaced of agents from the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force trying to interrogate water protectors. “The agents visited people’s homes without a warrant or a subpoena,” says Heath, who is involved with one of the investigations. “Of course, the protesters didn’t cooperate—it’s a violation of their free speech. If we really are worried about a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, why are we pulling off agents and resources of the border to target innocent water protectors? This is the kind of Orwellian doublespeak that needs to be exposed.”

Doubtless such concerns will be on minds of thousands of Native Americans and their supporters as they converge on the nation’s capital for “Rise with Standing Rock” in March. The four-day event is a “march in prayer and action.”

Such solidarity, Arnold says, proves that Standing Rock is bigger than any single issue or tribe. “It is a powerful global phenomenon that highlights the importance of respecting indigenous nations and their right to protect their land and resources,” he says. “There also is a sense of urgency—that we cannot spend the next four years pretending climate change will go away or renewable energy will create more jobs. We have to stay focused on the matter at hand.”

Brian Patterson agrees: “It feels like Watergate all over again, with the chaos that’s coming out of Washington. Only this time, much of the damage, particularly to the environment, is irreversible. The time to act is now.”