Motor City Mentor

David Bing ’66, H’06, NBA legend, entrepreneur and former Detroit mayor, molds next generation of leaders

When David Bing ’66, H’06 delivers the keynote address at this fall’s Coming Back Together (CBT) gala, he will reflect on a rich and varied career in sports, business, politics and philanthropy. Do not expect Detroit’s former mayor, however, to keep the spotlight on himself.

“CBT is about people,” says Bing, speaking by phone from his office in Detroit, near downtown’s beautifully restored riverfront. “In my four years at Syracuse, I don’t think we had more than 100 African American students on campus. I still keep in touch with many of them. If you put others first, you’re more likely to succeed yourself.”

This approach permeates the Bing Youth Institute (BYI) and its mentoring program, Boys Inspired Through Nurturing, Growth and Opportunities (BINGO), both of which the seven-time NBA All-Star founded in Detroit to help young men of color. In 2014, BINGO had about 40 students in a half-dozen schools. Today, those numbers have nearly tripled, and include more than 100 mentors.

The plight of the young African American male has reached epidemic proportions, with 62 percent of Detroit youth coming from single-parent homes. Many have no fathers nearby or positive male role models in their lives. A self-proclaimed “relationship guy,” Bing, 73, is reversing this trend by providing leadership in the face of adversity.

“Mentoring reinforces positive decision-making, increases self-esteem and helps young men become more productive individuals,” says Bing, also a self-made industrial magnate. “Decreasing the high school dropout rate [whose national average is 40 percent among African American males] increases job readiness.”

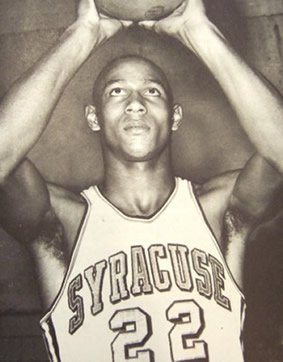

Bing is so chill that it’s easy to forget he is an NBA Hall of Famer who, along with Jim Boeheim ’66, G’73 and others, helped resurrect Syracuse basketball in the mid ’60s. In addition to holding the University scoring record for 20 years, Bing earned NCAA All-America honors (Syracuse’s first in the sport in four decades), and was the team’s first student-athlete to have his uniform retired.

Credit the legendary Ernie Davis ’62 for convincing Bing to choose Syracuse over Michigan and UCLA. Bing’s tireless work ethic and team-oriented approach to offense—he always looked for an open teammate before taking a shot—compensated for his average size and lack of depth perception, the result of a childhood eye injury.

“My parents migrated from the South to Washington, D.C., to find work,” says Bing, whose father was a church deacon and whose mother was a housekeeper. “I guess our family was poor and didn’t know it because we always shared whatever we had with people who were less fortunate. This idea of working together—building community—spilled over into other areas of my life, including basketball.”

At Syracuse, Bing struck up a friendship with future Pro Football Hall of Famer Floyd Little ’67, H’16. They were part of a select group of African Americans, including rebounders Vaughn Harper ’68 and Sam Penceal ’66, who helped change the complexion of NCAA sports.

Little recalls that, even as a freshman, Bing exuded a quiet confidence. “He’s always been a great leader,” says the retired Denver Bronco, who is a charter CBT participant and former special assistant to Syracuse’s athletics director. “I couldn’t be prouder of Dave’s accomplishments. Everything he touches turns to gold. He is, in my opinion, one of the nicest human beings you will ever meet.”

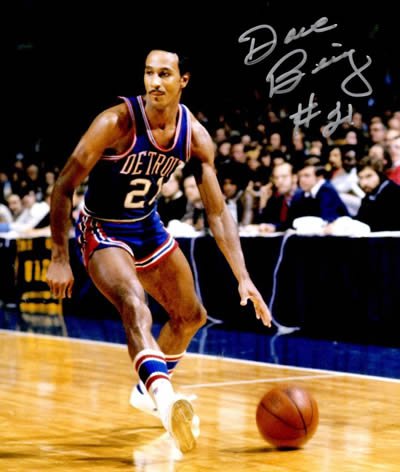

After earning a bachelor’s degree in economics, Bing was selected second overall by the Detroit Pistons in the 1966 NBA Draft. His speed and athleticism breathed new life into the franchise—a seemingly perpetual basement dweller—and affirmed his place as one of the league’s top point and shooting guards. Not even a freak accident during a 1971 preseason game, in which Bing suffered a detached retina, stifled his drive. Three months later, he was back in the paint, shooting, passing and hustling rebounds better than ever. (His free-throw percentage and overall defensive play improved for a while, after his injury.) He played seven more seasons, with stopovers in Washington, D.C., and Boston before retiring in 1978.

Bing’s 12-year NBA run netted him almost every conceivable honor, including Rookie of the Year, the J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award and spots on the NBA and Sports Illustrated lists of the Top-50 players of all time. Yet, the buzz of celebrity never did much for the man Sport magazine famously dubbed “Mr. Unsung-About.” Growing up poor, he admits, kept him humble.

“Neither of my parents graduated from high school,” Bing says, implying that their lack of education, combined with a blood clot in his father’s brain, limited their job prospects. “I also witnessed a lot of segregation in nearby Maryland and Virginia. It made me sensitive to what people go through.”

A bricklayer by trade, Bing’s father stressed the importance of having a firm foundation in life. Bing took this to mean education and, during NBA road trips, soaked up books on business, finance and industry. While most of his teammates played golf in the offseason, he worked—at Chrysler, a bank, a small steel company—in preparation for the inevitable transition to post-sports life.

In 1980, Bing opened a small automotive supply company in Detroit, later acquiring a metal-stamping business and a construction firm. The Bing Group quickly became the nation’s 10th largest black-owned business, with annual sales of more than $61 million.

“I grew the business from four employees to about 1,300 people,” says Bing, who sold the company in 2009. “I was glad to give people an opportunity to do something they believed in.”

Adds Little: “Dave took me on a couple of tours of his factory. He was very proud of his employees.”

Bing was of retirement age when he ran for mayor in 2008. A dyed-in-the-wool Democrat, Bing won a special election to finish the final months of Kwame Kilpatrick’s term. (Kilpatrick resigned, as part of a plea bargain for perjury.) Indeed, Bing inherited a mess—a city teetering on bankruptcy, awash in crime, corruption and a shrinking tax base. “None of us wanted him to do it,” one of his daughters told Sports Illustrated. “He felt he had to.”

Just as he had done on the court and in the boardroom, Bing quietly charted a path to success. He not only helped revitalize Detroit’s finances, but also repopulated the city and improved its citizens’ quality of life. His mission centered on changes to public safety, public transportation, public lighting, urban blight, and parks and recreation centers.

Importantly, Bing evoked what put Detroit on the map in the first place: entrepreneurship. In lieu of a well-oiled private market, he teamed up with local and national foundations to sow the seeds of small-business ingenuity and innovation. “The turnaround our city is enjoying now didn’t begin yesterday. It started while I was in office,” Bing insists. “I don’t take credit for it because I had a lot of really good people in my administration. I never asked them to do anything I wouldn’t do.”

Bing may be a reluctant celebrity, but he is quite the opposite as far as philanthropy is concerned. When Detroit Public Schools threatened to cut its physical education program in the 1980s, Bing famously raised more than $350,000 to ensure its survival.

At Syracuse, his largess has taken various forms, from chairing the inaugural Our Time Has Come Scholarship campaign (raising more than $1.2 million in 1987) to establishing an eponymous scholarship for African American and Latino students. He also is a longtime member of the College of Arts and Sciences’ Board of Visitors.

Derrick Coleman ’15 considers himself “living proof” of Bing’s impact. Raised in the Motor City, the star rebounder never met his biological father, but, in Bing, found a mentor and a father figure. The two formed an instant bond, with Bing guiding Coleman to Syracuse, where he held an all-time scoring record, and was picked No. 1 in the 1990 NBA Draft.

“Dave really took me under his wing,” says Coleman, who met Bing when he was 13. “I remember him telling me about the 1967 riots, which took place at the corner of 12th and Clairmount, near where I used to live in West Detroit. Dave and [Tigers left fielder] Willie Horton went there to defuse the situation and get some understanding. They worked with Samuel Washington [athletics director of St. Cecilia School] to keep the gym open all day, so kids would play there and stay off the streets. Today, anybody who is anybody in basketball has played in St. Cecilia’s Gym.”

Like Bing, Coleman is an NBA All-Star who has reinvented himself as a community leader. When he is not volunteering at the BYI or running his own youth basketball association, Coleman regularly drives an hour north to deliver bottled water and eating utensils to those hardest hit by the Flint water crisis—traits instilled in him by his idol.

“Helping others is in Dave’s DNA,” says Coleman, who, after a 25-year break from his studies, earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Syracuse. “He takes time to help others understand who they are, where they’re from and what they’re going through. He certainly did that for me. There would be no Derrick Coleman without Dave Bing.”

Bing takes the praise in stride, attributing much of his success to “good friends and good health.” That genuine affection for helping others reflects his belief in the importance of giving back. “Whether we are in Syracuse or Detroit, we need to put our arms around people and let them know we care about them,” Bing says. “We need to help them succeed.”