University Mourns Loss of Author, War Correspondent Michael Herr '61

Alumnus chronicled Vietnam War in 'Dispatches,' 'Apocalypse Now,' 'Full Metal Jacket'

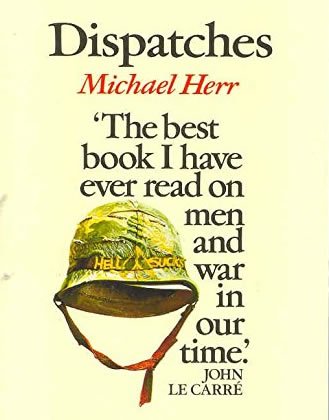

The College of Arts and Sciences is mourning the loss of one of its most inimitable voices. Michael Herr ’61, author of the Vietnam War classic “Dispatches” (Vintage Books, 1977), died on June 23 at a hospital near his home in Delhi, N.Y. He was 76.

Herr left behind a small but visceral body of work that included “Kubrick” (Grove Press, 2000), an unflinching look at his 20-year friendship with the great filmmaker, and “Walter Winchell” (Knopf, 1990), a pseudo-novel about the fabled postwar journalist and ideologue.

It was “Dispatches,” however, that launched Herr’s career, and helped galvanize a literary movement combining traditional journalism and nonfiction writing known as New Journalism.

Hailed by The New York Times as a “glaringly intense, personal account” of the Vietnam War, “Dispatches” was based on Herr’s 18 months as a war correspondent, in which he traveled the country without restrictions, often embedding himself with the soldiers he was covering. Sometimes, Herr carried a rifle to gain access. “I only had to use a weapon twice,” he told The Boston Globe. “And I had to, I had to. It was impossible not to.”

The result was a series of reports for Esquire that, a decade later, was published in book form as “Dispatches.” The book’s success led to national celebrity and a brief stint in Hollywood, where Herr worked as a “rewrite man.” His best known projects were “Apocalypse Now,” for which he wrote the narration for Martin Sheen’s character, and “Full Metal Jacket,” whose screenplay Herr co-authored with Stanley Kubrick and novelist Gustav Hasford.

Four decades on, the effect of “Dispatches”—an “acid-rock love letter of memories, reportage and anecdotes,” writes Matt Gallagher in The Paris Review—is keenly felt.

“‘Dispatches’ will be read for as long as people are engaged in or contemplating violence and want a better understanding of what a war actually means, on the ground, to human beings,” says George Saunders G’88, a professor of English and New York Times bestselling author. “[Herr] will be missed, also, as a form of artistic conscience. Those of us who knew and loved him were ever-mindful of his presence, and tried to work to his level, so to speak, and honor the level of artistry and integrity his work represented.”

Peck Professor of Literature Mary Karr also was close to Herr. In “The Art of Memoir” (HarperCollins, 2015), she writes an entire chapter about “Dispatches,” devoting nearly a dozen pages to the book’s 500-word prologue, which begins with Herr’s study of an antique map of Vietnam that hung on the wall of his Saigon apartment.

“A book known for its bizarre, hallucinatory surface opens with [a description] of a static physical artifact,” writes the acclaimed poet and memoirist. “It’s a quiet scene any reader can imagine herself inside. Then, line by line, he builds up to the jazzy surface his book is known for.”

Karr says the map embodies the book’s “central worry”—that the kinds of information most war correspondents crave often trivialize the mystery of suffering. “Michael Herr taught us the horrible moral responsibility of writing about other human beings who fill you with horror and pathos,” she says. “The poetry of the idiom he discovered made English, itself, a deeper language. … The planet weighs less without him.”

Born in Lexington, Kentucky, Herr was raised in Syracuse, where he lived on Crawford Avenue and attended Nottingham High School. As a student, Herr blended in easily with the literati. In high school, he befriended John Berendt, who would go on to write “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” (Vintage, 1994). At Syracuse, Herr and Joyce Carol Oates ’60 worked on a literary magazine together.

But the call to adventure proved irresistible. Herr dropped out of college and spent the next several years hiking through Europe, serving in the Army Reserve and writing for The New Leader and Holiday magazines.

In late 1967, Herr persuaded Harold Hayes, editor of Esquire and a main architect of New Journalism, to make him a war correspondent. On the eve of the Battle of Khe Sanh and the Tet Offensive, generally regarded as the war’s darkest hours, Herr made his way to Southeast Asia with a visa and $500. Hayes later admitted that he promptly forgot about Herr, who wasted no time in making himself known among the press corps. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, spotting Herr’s Esquire credentials, thought he was there to write “humoristical” pieces.

Herr returned to the United States in 1969 and spent the next 18 months piecing together “Dispatches” before his wartime experiences (exacerbated by drink and drugs) caught up with him. In 1971, he suffered a nervous breakdown, along with a brief separation from his wife, and did not write anything for the next four years.

“I flipped out,” Herr later admitted. “I experienced a massive physical and psychological collapse. I crashed. I wasn’t high anymore. And when that started to happen, other things started to happen, too; other dark things that I had been either working too hard or playing too hard to avoid just became unavoidable.”

After reuniting with his family, Herr managed to finish “Dispatches” and publish it to great acclaim. The New York Times praised it as one of the best books on the Vietnam War. Novelist Robert Stone, in his review for the Chicago Tribune, declared it the “best personal journey about war, any war, that any writer has ever accomplished.” British spy novelist John le Carré concurred, calling “Dispatches” the “best book … on men and war in our time.”

Perhaps gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson got it right when he said that Herr “[put] all the rest of us in the shade.”

Anthony DeCurtis, an award-winning author and longtime Rolling Stone contributor, credits Herr for inventing wordplay that “read like rock ’n’ roll on the page, but was spellbindingly cinematic.” His point is illustrated by the following passage:

“You could be in the most protected space in Vietnam and still know that your safety was provisional, that early death, blindness, loss of legs, arms or balls, major and lasting disfigurement—the whole rotten deal—could come in on the freaky-fluke as easily as in the so-called expected ways, you heard so many of these stories it was a wonder anyone was left alive to die in firefights and mortar-rockets attacks.”

Herr continues: “Fear and motion, fear and standstill, no preferred cut there. No way even to be clear about which was really worse, the wait or the delivery.”

DeCurtis says that while musicians responded almost immediately to the Vietnam War, writers and filmmakers took longer to weigh in on it. “‘Dispatches’ was among the first, the best, and the most influential,” says DeCurtis, who also teaches English at Penn. “The book remains a classic, and has set the standard for all the writing about the Vietnam War—and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—that has followed it.”

No doubt that Tobias Wolff, who channeled his own Vietnam experiences into a critically acclaimed novella and memoir, found a kindred spirit in Herr. The former Syracuse professor, now on the faculty at Stanford, applauds Herr’s originality. “‘Dispatches’ is not only an indelible portrait of American troops living on the edge in Vietnam; it is one of the finest accounts ever written of young men at war,” says Wolff. “He was my dear friend, and I will miss him.”

Wolff adds there is more to Herr than war-correspondent lit. He singles out a collection of celebrity profiles titled “The Big Room” (Summit Books, 1987) and “Walter Winchell” for their adventurousness in language and form. “They are both, at bottom, meditations on the American obsession with celebrity, a condition that [Michael] abhorred and could not avoid, at least among writers and readers,” Wolff says.

Toward the end of his life, Herr distanced himself from writing and became a devout student of Buddhism. Splitting time between his homes in London and Cazenovia, New York (which he sold in 2005), he eventually retired to Delaware County, in the shadow of the Catskills.

Chris Kennedy G’88, professor of English and director of the M.F.A. program in creative writing, remembers Herr being genuinely humble. “Michael was a deeply spiritual man with a sardonic wit,” he says. “He was a pleasure to be around, always encouraging of younger writers and always interested in other people, deflecting attention away from himself.”

Adds Saunders: “Once a person has had the good fortune of meeting or reading someone like Michael, they’re ever-after blessed. They can’t help but carry him around in the way they understand the world.”