The Perfect Existence

Pedro Cuperman, Argentine scholar and Point of Contact founder, dies at 80

Hector Torres ’84 and Anne Marie Prucha ’87 owe their marriage to Pedro Cuperman, the eminent Argentine scholar who died in Buenos Aires on July 12, 2016, at age 80.

It all began on the first day of class in the fall of 1983, when they sat next to each other in an upper-level Latin American literature course, taught by Cuperman. They gradually got up the nerve to talk to one another, and, unbeknownst to their professor, began dating. When Cuperman encouraged his students to see The Return of Martin Guerre, the 1982 French drama playing at the nearby Manlius Art Cinema, the couple traded knowing glances.

“The following day, we saw Pedro on the Quad, and told him how much we liked the movie,” says Anne, whose father, John, was then Syracuse’s vice chancellor of academic affairs, and whose sister Barbara worked in the Department of Earth Sciences. (Coincidentally, Cuperman taught Latin American literature in the Heroy Geology Building, where John also was an Earth Sciences professor.) “When Pedro realized that we had gone to the movie together, he got a big grin on his face, and was very amused. It was then that he started to take credit for getting us together.”

That was 33 years ago. In a bittersweet twist of fate, Hector and Anne will celebrate their 30th anniversary next summer, a year, almost to the day, after Cuperman died.

“We had a great friendship with him,” says Anne, a Spanish professor at the University of Central Florida. She, along with Hector, a prominent advertising executive, kept in touch with Cuperman after graduation, often visiting him on campus and in New York City. “One day, Hector and I took our daughters to see him, while we were in Syracuse, visiting my parents,” she recalls. “Of course, Pedro charmed our girls immensely, chatting with them and giving them poetry books. He even asked our daughter, Sofia, to marry him. She was seven. … It was sweet.”

Growing up in middle-class Buenos Aires, Cuperman was something of a charmer. Credit his parents, who emigrated from Eastern Europe to Argentina to avoid Jewish persecution and the tension of marrying out of their social class, for instilling in him wanderlust and a sense of adventure. Or maybe there was something in the air of the sprawling coastal city—affectionately known as the “Paris of South America,” for its fusion of Latin American and European values—that enlivened him. In those days, Buenos Aires already was a bustling, cultural metropolis, and its rhythm coursed through his veins like a vibrant tango. He and the city were a study in contrasts.

No one loomed larger in Cuperman’s childhood than his sister, Lila. Four years his senior, she exposed him to a world of art and ideas—notably, the texts of Freud, Hesse and Jakob Wasserman—that were well beyond the purview of the Yeshiva and the public schools he attended.

Still, Cuperman's Jewishness remained integral throughout his life. “In school, he learned the Torah in Hebrew, and could recite long passages from memory, even as recently as last spring,” says nephew Joseph Kugielsky, who, along with his wife, Anne, was close to Cuperman. "Pedro said his knowledge of Hebrew—being able to read texts in the vernacular—helped with his academic study of philosophy."

Cuperman joked that his mother wanted him to be a pharmacist because she “liked taking medicines,” so he enrolled in medical school. On the first day of class, when one of his professors announced that he wouldn’t be teaching Latin because it was “ancient history,” Cuperman darted for the door.

He went on to earn philosophy degrees from the Jose Manuel Estrada Institute and University of Buenos Aires, and then received a prestigious, two-year fellowship to Banaras Hindu University in Northern India. Lila recalls how her brother, terrified of flying, persuaded Argentine President Arturo Illia to let him travel by ship. “Pedro sailed to Italy and through the Suez Canal, and then arrived in India,” she said. “He spoke virtually no English and certainly no Hindi or Urdu or any other language of India.”

In the ancient city of Varanasi, Cuperman trained under T.R.V. Murti, a leading scholar of Indian Mahayana Buddhism, and befriended Mexican poet and diplomat Octavio Paz. His social circle widened to include writer Carlos Fuentes, who, along with Paz, Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar and Mario Vargas Llosa, ushered in the Latin American literary movement called “El Boom.” When student unrest and rebellion began sweeping the globe, Cuperman left for Rome and points beyond.

“My most beautiful day was the first of May, 1966, when I arrived in Paris, which was great and exciting, and filled with the youthful fervor of the era,” Cuperman told Joseph Kugielsky. “It was the beginning of a youthful revolution that would engage the world at large.”

Indeed, Cuperman was seduced by the city’s burgeoning counterculture movement. When student activism temporarily shut down Paris in 1968, Cuperman hopped the pond, and took a teaching post at the University of Connecticut. Lila remembers Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges visiting Cuperman and his Australian bride, Anne, in the sleepy town of Storrs, Conn. “Anne and I argued over who would get to cook for Borges,” Lila says. “One time, Borges came into the kitchen totally naked. I mentioned to him that he was naked, and he replied, ‘That’s okay. I’m blind.’”

By the time Cuperman got to Syracuse in 1976, he had six years of teaching at New York University under his belt, along with multiple grants and papers. It would be in the College of Arts and Sciences that he would do his most salient work. Over the next four decades, Cuperman, along with colleagues such as Willie Meltzer and Myron Lichtblau, helped propel the Spanish program to international prominence, while overseeing the Point of Contact (POC) Gallery and publications. Much of his work contested the boundaries of multicultural art, teaching and research.

Ironically, Cuperman wasn’t given his due until 2014, when Gail Bulman G’96, associate professor of Spanish and former chair of the Department of Languages, Literatures and Linguistics, mounted an effort to promote him to full professor. “As a teacher, scholar, colleague and person, Pedro always made you think outside the box,” she says. “Every encounter with him was an experience that opened you to a new world and to new ways of seeing your world.”

Another cross-disciplinary colleague was Cathryn Newton, dean emerita of A&S and the University’s only Professor of Interdisciplinary Sciences. She got to know Cuperman in the early ’90s, a particularly fertile period for him that saw two major symposia (one of which he organized for POC, with support from Lawrence University and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation), on top of his around-the-clock writing and curating. “Pedro embodied interdisciplinarity, and his role in Point of Contact and the Syracuse International Film Festival [SIFF] are two of many legacies in that realm,” she says. “Beyond that, he had the most remarkable capacity for human connection. He had a ready smile and quick wit. ... I appreciated his friendship and collegiality deeply.”

It didn’t hurt that Cuperman had truck with literati such as Borges, Fuentes and Umberto Eco. Former student Colleen Kattau G’87, G’92, an associate professor of Spanish at SUNY Cortland, says Cuperman was one of the last links to the Boom generation. “His associations with these internationally acclaimed authors provided material for an oral history that ought to be documented,” she says. “His legacy is distinctive, in that his work always focused on the intersections, or ‘points of contact,’ between and among artistic disciplines, bringing together, within a common space, poetry, literature, visual art, dance and music.”

Cuperman also was a formidable theorist, particularly involving semiotics and research methods. Proof of his versatility was found in a graduate film-theory course he co-taught with Owen Shapiro, the Shaffer Professor of Film, in the College of Visual and Performing Arts (VPA) for 19 years.

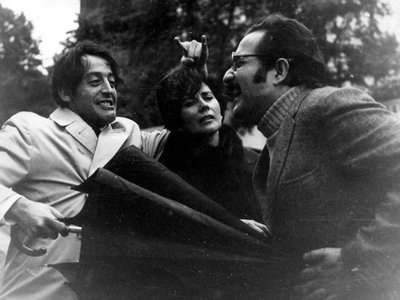

Shapiro recalls how, when they met in 1984, their connection was so instantaneous that they felt like long, lost brothers. “We became close friends and creative colleagues,” says Shapiro, co-founder and artistic director of SIFF and associate editor of many POC publications. “I’ve never known anyone as witty and brilliant as Pedro, who also was extremely modest about his scholarship and writing. ... His contributions to the intellectual and cultural life of the University were monumental.”

Shapiro, who also coordinates VPA’s film program, says he and Cuperman worked on four films, seven journal articles and six graduate seminars. “We also ate a lot of sushi,” he quips, adding that Cuperman was an avid sailor. “I remember watching Halley’s Comet [in 1986] with Pedro, from the deck of his boat at Man-O-War Cay in the Bahamas. We were sipping Argentinian Malbec, his wine of choice.”

No doubt that Cuperman’s miniature schnauzer, Oliveira, was part of the gallant crew. “He was Pedro’s companion, which many faculty and students will remember,” Newton adds.

Regardless of the medium, Cuperman was a relentless tinkerer, often fine-tuning content after it was published. He wrote or edited 10 books (most of which were translated into Spanish), including the novel For as Long as the Night Lasts (Point of Contact, 2011); the art books The River Woman (DOXA Publishing, 2013) and Midnight Nirvana at Times Square (Asunto Impreso Ediciones, 2011), both with artist Pedro Roth; and the POC poetry series “Corresponding Voices.”

Cuperman also edited monographs and catalogs, and published essays on the creative, performing and literary arts. Some of them took the form of “conversations” with notable artists, writers and thinkers. He once interviewed Mary Karr and Bruce Smith, writers and professors in Syracuse’s M.F.A. Program in Creative Writing, for a piece on sports and poetry. “Pedro was and is a great soul who combined intellectual curiosity, passion and literary, artistic and philosophical depth of understanding with humor and modesty,” Smith says. “He brought with him, wherever he went, an active and engaged openness.”

Liliana Porter and Ana Tiscornia—visual artists from Argentina and Uruguay, respectively—also found their way onto Cuperman’s radar. In a joint statement, they recount his fondness for discussing art and Borges; speaking Rioplatense (La Plata River Spanish); swapping jokes; and meeting up, when schedules allowed, in Buenos Aires, New York or Syracuse. “We will miss him, his humor and his intelligence,” they continue. “All the things we have lived together make the presence of Pedro in our heart a pleasant and very dear one.”

For all his success in the classroom, Cuperman probably will be most closely linked to POC—or Punto de Contacto, as it also called. Originally an NYU arts journal, it was founded by him in 1975 as a way to showcase the verbal and visual arts. A year later, he moved POC to Syracuse, where it evolved into a series of books and bilingual poetry editions, as well as a formidable gallery.

Shapiro, who helped reboot POC at Syracuse, credits Carole Brzozowski ‘81, then dean of VPA, for securing gallery space on East Genesee Street in 2005. Eight years later, POC moved into larger digs in The Nancy Cantor Warehouse on West Fayette Street, where it has been ever since. “Without Carole, there probably would have been no gallery. POC would have been just a publication series,” Shapiro surmises.

Today, POC boasts a rich array of events and activities, including a multicultural arts education program called El Punto. Some say Cuperman’s death provided a fitting conclusion to POC’s yearlong 40th anniversary celebrations.

“I was saddened by the news of his passing, and, yet, not surprised. Somehow, I felt that Pedro knew when and where his days would end," says Tere Paniagua ’82, one of his former students, who is executive director of the Office of Cultural Engagement for the Hispanic Community, based in A&S. “Pedro sure knew how to make a grand entrance and a dramatic exit.”

Sorting out his personal affairs has fallen, in part, to Paniagua, who probably was the closet thing to family Cuperman had in Syracuse. Paniagua also oversees the management of POC and La Casita Cultural Center, and is making plans for the former to house a permanent, searchable archive of Cuperman’s manuscripts (many of which remain unedited), audio and visual recordings and photos. "There is a treasure to be sorted out, digitized and cataloged," she says. "It’s rather comforting for me to begin to work on it, to ensure that his vision and his life’s work will be preserved for future scholars to be inspired by him."

Cuperman saw POC as a platform for rising stars and established talent. Many of them reflected his own brand of experimentalism. Leandro Katz, a celebrated Argentine writer, visual artist and filmmaker, grew up not far from Cuperman in Buenos Aires. Katz remembers him as a “relentless conversationalist [and] an avid reader with a virtuosic memory,” someone with whom he spent countless hours, walking and talking. “Pedro was able to recall the strangest events in Buenos Aires—different stories marked by the geography of the city, the apartments where he had lived, the bars and cafes where the best minds would meet and the clandestine sites of the Dirty War [an infamous campaign waged by Argentina’s military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983],” says Katz, who also has taught at William Paterson University in New Jersey. “Our favorite subjects were Borges, Judaism, the tango, street demonstrations, graffiti, poetry and philosophy. A great mind, how much we shall miss him.”

One of many artists with whom Cuperman teamed up was painter and sculptor Izhar Patkin. Their collaborative work Go East by Going West (Carla Sozzani, 1990) is a commentary on art, the New World, and Patkin's sculpture. Writing from Tel Aviv, the Israeli-born, New York-based artist reflects on Cuperman as a friend, teacher, mentor and inspiration: "I am glad to hear that Pedro was at peace with dying. I would expect no less of him. But I am not sure I am. I am so sad. His teaching changed my life. I am at a loss for words.” Cuperman wrote numerous essays about Patkin’s work, notably A Portable Paradise (Rena Bransten Gallery, 1988), in which Cuperman took up a series of Patkin’s paintings titled “The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden.”

Cuperman provided the impetus for one of Patkin’s signature works, "Where Each Is Both." In a video for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Patkin recalls how Cuperman ushered him into the world of manifestation vs. representation by instructing him to “make me a Shiva.” Patkin responded with a 14-foot, blown-glass dancing goddess, drawing on the legends of Shiva Nataraja, Carmen Miranda and Josephine Baker. Patkin says Cuperman helped him see the piece not as a representational sculpture, in the traditional sense, but as a manifestation of the divine.

“I found myself being a vessel of an idea that was radically expanding my artistic horizons and my Jewish and Western upbringings,” Patkin says in a separate interview. “Pedro took me on a profound journey that was illuminating and life-changing. He reminisced with me about how his stay in India had taught him the mastery of manifestation. ‘The statue is the god’ [Cuperman said]. He wanted me to experience the deep intimacy of art that occurs, when you do away with the distance that representation inflicts.”

Cuperman was particularly close to Pedro Roth, a Hungarian-born artist living Buenos Aires, who was with him at the time of his death. During a recent phone conversation, Roth relives how his friend of 30 years "came home" to die, amid multiple organ failure. That Cuperman spent his last days in a Buenos Aires hospital, sharing a room with a convicted felon, chained to his bed, touches of irony. “The police were always there, so that the guy wouldn’t escape. It was like the death of Christ,” says Roth, alluding to the Penitent Thief, one of two unnamed persons mentioned in the New Testament version of the Crucifixion of Jesus. “Pedro knew it was time.”

Roth, whose collaborations with Cuperman spanned such topics as The Last Supper and Jewish mythology, says his friend remained every bit the professor until the end, entertaining a steady stream of visitors. “Many people came to see him,” Roth says. “It probably was the first time the hospital ever hosted a famous philosopher. Throughout it all, Pedro remained meditative and reflective. His last word to me was ‘perdón’ [‘pardon’].”

In keeping with Jewish funeral tradition, Roth and Joseph Kugielsky arranged for Cuperman to be buried within 24 hours of his death. In attendance was a small group of friends and acquaintances. Two months on, Roth still marvels at his friend's prolific output. "Pedro's legacy was 'don’t stop.' Work. Work. Work," Roth adds. "He never looked back, but always ahead. Work was his life.”

While Cuperman’s death has sent shockwaves all over the world, nowhere have they been more keenly felt than in his adopted hometown of Syracuse. Christopher Kennedy G’88, associate professor and director of the creative writing program, says Cuperman’s passion for literature and the visual arts catalyzed the University’s cultural life. “His charm and energy will be sorely missed by those affected by his enthusiasm and tireless pursuit of ways to bring the arts together,” he says, alluding to POC and its “Corresponding Voices” book series.

“Point of Contact was Pedro’s 40-year-old ‘baby,’” Spanish professor Gail Bulman says. “There’s really no place else in Central New York where people can immerse themselves in such a diversity of cultures, art forms and ex-centric thinking. Yes, Pedro will be missed, but he won’t be forgotten.”

Bulman’s colleague Stephanie Fetta says Cuperman was every bit adventurous as he was cosmopolitan, with his dual residencies in Syracuse and Buenos Aires and checkered past. “His two-year stay in Varanasi gave a breadth and dimension to his creative and scholarly acumen,” she says, adding that few people knew he was a seafarer. “I had no sooner met him than he offered to take me out on his boat—an overture of friendship, welcoming me to campus and attesting to a flair for life.”

Libertad Garzón G’07 is one of many former students trying to make sense of Cuperman’s death. While teaching Spanish at Syracuse, she worked on various POC publications before going south of the border. Today, she is a postdoctoral fellow at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “Pedro was the kind of person you’d meet only once in a lifetime, so he became a turning point for many of us who could see the significance of his philosophy of life,” she says. “His fascination with his boat and with the sea helped me see the way he understood life. He always showed good mood in bad weather, saying the solution to a problem was often less interesting than the problem itself.”

An avid traveler, Cuperman had a lust for adventure. He and Fernando Diz, the Martin J. Whitman Professor of Finance, often regaled one another with stories of their exploits—such as the time, four years ago, when Diz flew solo from Syracuse to Buenos Aires in his single-engine aircraft. “Pedro thought that, for men, who can’t experience the wonder of maternity, stories of travel and navigation were a close substitute,” Diz says. “He told me, 'Navigation doesn’t have a future, but it has a horizon. In the horizon, one is young forever.'"

Perhaps it was Cuperman’s no-holds-barred approach to life that made him successful. And imperfect. “Sadness and loneliness were just as important to him as love and laughter. They remind us that we’re alive," Garzón adds.

Kattau agrees, opining that Cuperman was genuinely in love with life, and enjoyed “inventing”—a key word for him, she points out—and putting a fascinating twist on things. “One of his most famous quotes was ‘How lucky I was to have known you,’” she says. “‘Otherwise, I would’ve spent the rest of my life trying to forget you.’”