New Book Traces Wikipedia's Origins to 18th-Century Encyclopedia

Krista Kennedy’s work raises questions about who and what is a writer in computer age

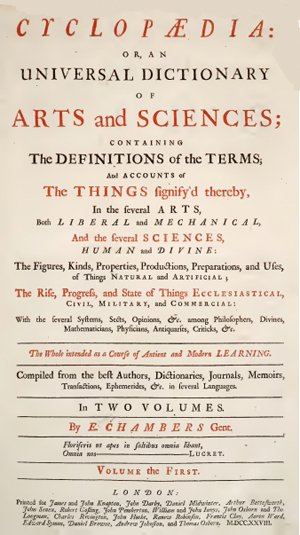

According to Wikipedia, Ephraim Chambers’ 1728 “Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences” was one of the first general encyclopedias produced in English. A very long subtitle summarizes the broad goals for the two-volume work, concluding, “The Whole Intended as a Course of Ancient and Modern Learning.” The entry in the very modern online “free encyclopedia” does not mention Wikipedia’s debt to the 18th century publication. Krista Kennedy, associate professor in the College of Arts Sciences’ Department of Writing Studies, Rhetoric and Composition, explains the connection in a new book.

In “Textual Curation: Authorship, Agency, and Technology in Wikipedia and the Chambers’ Cyclopedia,” published this month by University of South Carolina Press, Kennedy describes the editing and production process of “Cyclopædia” and Wikipedia. Both collaborative collections of knowledge raise questions about the ways writers interact with technology, she says.

“We do tend to think about Wikipedia as a brand new phenomenon,” Kennedy says. “In some ways it is. Without the infrastructure, it would not have the span and reach and real-time updating it does.” But it shares with Chambers’ “Cyclopaedia” the goal of making knowledge accessible to as many people as possible, she explains. And it, too, challenged conventions of its time.

The “Cyclopædia” attempted to be comprehensive, says Kennedy, who did research at the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford and the British Library, among others. “It’s cross-indexed, which was heretical at the time,” she explains. “That was seen as imposing man’s order on God’s world. Rather than limit the readers to the categories, he wanted to let them find their own path. When topics are placed next to each other, readers find new connections.”

The encyclopedia did not claim objectivity, but sought to make emerging knowledge in natural philosophy available. “This book tries to gather together everything people need to know about legal, religious and military issues as well as the philosophy of the natural world,” Kennedy says. “It does its best to use scientific language rather than terms of alchemy, which were previously used to explain how the world worked.”

Chambers wrote that his goal was to include a wide range of people, including illiterate craftspeople and titled gentry. In the 18th century, contributions were sent through mail and private secretaries, and scientific societies published papers that Chambers recomposed for the “Cyclopædia.” Chambers was the “central curator, marshaling the information and vetting it and composing it,” Kennedy says.

Readers were “people who had money,” Kennedy says, but also shopkeepers, clockmakers, lawyers and doctors. “That was his goal,” she adds. “He paid attention to arguments for democratizing knowledge and the promise of educating the working class, which was a radical idea at that time. ‘Real knowledge’ at the time was the province of gentlemen. Women are not understood to be generating anything except the science of household management.”

The “Cyclopædia” was later translated into French and became the basis for “Encyclopédie, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts,” published in France between 1751 and 1772. After the French Revolution, that work was translated into English and became the basis for The Britannica. The 1911 Britannica became the initial text dump that Wikipedia was built upon.

Wikipedia’s crowdsourced format was “heralded as both the best possible future of the intellectual commons and the demise of civilized, rigorously vetted reference texts,” Kennedy writes in the book’s introduction. Wikipedia’s incremental, public collection of information “disrupted cherished cultural tropes concerning authorship and even who or what an author might be,” she continues. It also disrupted the concept of writing by including not only narrative text and images, but also metadata, links, code and more, she says.

Some of Wikipedia’s contributors support eventualism, the idea that “enough people will come along and errors will be corrected,” Kennedy explains. That self-correction “happens more often than not,” she adds.

The book joins other scholars in addressing “the question of whether new media is really new,” Kennedy says. “It speaks to some of the ways Wikipedia has been developed and where it will go in the future. It raises questions about who and what is considered a writer when we have bots and computers.”

The question of writers’ agency is especially important in thinking about the future of writing, she says: “We can say, ‘The robots are coming for us.’ Or we can say, ‘What does it mean to work alongside machines and how can we make this sort of situation work for us?’”