From Locker Room to Boardroom

Former NHL players Clint Malarchuk and Mike Gaul are using a new playbook to chart life after hockey

Some of you are too young to remember Jim Murray, who made a brief splash with the Los Angeles Kings in the ‘60s, but he’s the one who said that hockey is murder on ice.

That statement is not lost on Clint Malarchuk and Mike Gaul, two former NHL players who understand, all too well, the challenges of the “Fastest Game on Earth.” Malarchuk, a former All-Star goalie, is best-known for suffering a life-threatening injury in 1989, when his neck was slashed by a hockey skate. The incident was exacerbated by a lifelong battle with anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder that later manifested in the form of alcoholism and a suicide attempt.

Gaul, a journeyman blue-liner who spent most of his career in the minors, endured a series of mind-numbing concussions. He was done by age 30. “I was uninsurable because I had so many concussion issues,” says Gaul, who briefly played with the Colorado Avalanche and Columbus Blue Jackets. “I realized that I had to start exploring other options.”

Like Murray, Malarchuk and Gaul are using a new playbook to chart life beyond the rink. That’s why they visited Syracuse University in March, when most of their peers were hitting the links.

Both skaters are part of a new partnership between the BreakAway Program of the NHL Alumni (NHLA) Association and the Barnes Family Entrepreneurship Bootcamp for Veterans with Disabilities (EBV), a 14-month program involving a consortium of universities across the country. At Syracuse, they joined nearly 30 military veterans with disabilities to get hands-on training in entrepreneurship and small-business management.

To say that the EBV program is “rigorous” is to flirt with understatement. For starters, participants are selected from a nationwide pool of several thousand applicants and, in many cases, are “serial entrepreneurs,” with multiple ventures at the ready. The first and third phases constitute a 30-day online course and a year of support and mentoring, respectively. The program’s second phase, which includes a nine-day residency at Syracuse or another EBV institution, is grueling. Participants receive college-level instruction in courses ranging from accounting and economics, to idea recognition and marketing, to operations and human resources.

During a recent break between classes, Malarchuk and Gaul look as if they’ve stepped off the ice. “Did you just ask me a question?” Malarchuk wearily laughs, after making introductions. “My brain is fried.”

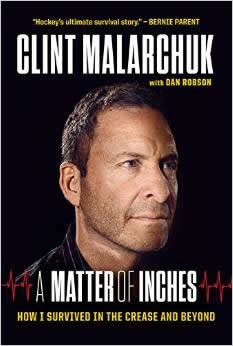

With a scar on his neck and a bullet in his skull (from a self-inflicted gunshot), Malarchuk, 53, is using the EBV program to piece his life back together. Compared to his classmates, all of whom suffer from various physical or psychological issues, Malarchuk isn’t out of the ordinary. But his story—a cautionary tale about the perils of professional hockey—is certainly extraordinary. Much of it is captured for posterity in A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond (Triumph Books, 2014), Malarchuk’s unflinching look at the game and the battle with his inner demons. One of his goals with the EBV program is to parlay his memoir into a successful speaking career, while raising awareness of and support for people affected by mental illness.

“Mental illness is still considered a private issue because its effects are often unseen,” says Malarchuk, who has been struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) since his 1989 injury. (His PTSD kicked into high gear in 2008, when, in response to a near-identical accident involving Florida Panthers forward Richard Zedník, the media spent weeks reliving the Malarchuk episode.) “I’d like to see a system set up, such as a 24-hour help line, where an NHL player can get confidential help without risking his career.”

Gaul applauds these efforts, saying it’s been only in the past few years that scientists have confirmed the link between repetitive brain trauma and post-concussive disorders, such as dementia and depression. “In the old days, you’d ‘get your bell rung,’ shake it off, and go back out on the ice,” says Gaul, 42, who spent most of his decade-long career in the American and Swiss hockey leagues. “Thanks to Clint and others, we’re starting to look at mental health differently. That’s probably what bonds us here [at the EBV program] and makes it all the more remarkable.”

Mike Gaul at The Outdoor Classic at Hersheypark Stadium, 2013 (Photo by Kyle Mace)

Going to War

Malarchuk and Gaul owe part of their transformation to NHLA Director Wendy McCreary. Last year, she and her colleagues approached James Schmeling, co-founder and managing director of Syracuse’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF), with the idea of embedding former hockey players with post-9/11 veterans with disabilities in a classroom environment. The EBV program, with its cutting-edge, experiential training in business, seemed tailor-made.

That the NHLA has a history of sending players on goodwill tours around the globe only reinforced the concept. “Mike and Clint were selected for the adversities they’ve overcome during their tenures as hockey players and their transitions to post-hockey life,” says McCreary, daughter of the late Canadian forward Keith McCreary. “Other players were considered, but Mike and Clint seemed to offer the most, in terms of different backgrounds and journeys. They were hand-selected for their commitment to the program.”

McCreary says the similarities between veterans and athletes are striking, citing a “parallel of dedication, motivation, and emotion.” But where hockey players often part ways with their professional counterparts is in the area of entrepreneurship. Despite having the lowest average salaries in professional sports, NHL players are known for their financial prowess. As a result, they’re less likely to file for bankruptcy or undergo financial duress. The late restaurateur Tim Horton, venture capitalist Richard Stromback, and winemaker Wayne Gretzky are a few of the many skater-turned-entrepreneur success stories.

According to Entrepreneur Magazine, NHL players also contend with other factors, not the least of which is a short playing window. “The average NHL career is five-and-a-half years, which represents a tiny fraction of one’s total career span,” writes Jaia Thomas, a Los Angeles-based sports and entertainment attorney. “Realizing the brevity of their career, players understand the importance of planning ahead. Entrepreneurs and aspiring entrepreneurs would be wise to do the same.”

Malarchuk and Gaul think the differences between NHL players and other pro athletes run deeper. “Have you ever seen a hockey player with an entourage?” Malarchuk asks incredulously. “I think it goes back to how we were treated growing up. There were different expectations of us. We weren’t the big men on campus, and we didn’t have to deal with agents. I think it’s made us more approachable, as athletes and as businesspeople.”

Gaul, an affable, self-avowed “serial entrepreneur,” agrees with this assessment. “I’ve mixed with a lot of people in other sports, and I have to say that there’s nothing like the camaraderie in a hockey dressing room,” he says. “I suppose it’s similar to what you’d find in the military. Both have a clear chain of command and a strong commitment to teamwork. And there’s this whole idea of ‘going to war.’ Being in the EBV program has made me feel like a rookie again.”

Executing the Vision

While the partnership between the NHLA and EBV is as new as a resurfaced sheet of ice, Malarchuk and Gaul already give it high marks. In a way, the collaboration is a natural extension of the groundbreaking work for which the NHLA’s BreakAway Program is known. As Malarchuk was making the bumpy transition from player to goalie coach in the late ‘90s, it was the BreakAway Program (then known as Life After Hockey) that provided him with various support services.

In his keynote address at the EBV program’s opening ceremony at Syracuse, Malarchuk admitted his personal struggles are far from over and that entrepreneurship is one way he is reclaiming his life. “There are a handful of things I have to do every day,” said the former netminder for the Quebec Nordiques, Washington Capitals, and Buffalo Sabres. “I have to take my medication, work out, meditate, follow my [Alcoholics Anonymous] 12 Steps, and be of service to other people. As a public speaker, I’m reminded that giving advice doesn’t take the place of giving to self.”

Today, Malarchuk lives on a ranch near Reno, Nevada, where he divides his time between public speaking and working as an equine dentist and chiropractor. He reserves special praise for his wife, Joanie, who manages much of his career. “She has stood by me through it all,” Malarchuk says a few days later, over a cup of coffee. “Nobody deserves the patience, love, and grace she has shown me.”

In a recent email exchange, Joanie returns the compliment: “Through all the ups and downs of his life, Clint has shown amazing strength and incredible courage. Even as hard as it was for Clint to write his book, it’s given him a new purpose and a sense of peace. I’m so proud of him.”

Gaul also has turned a negative into a positive. Although he hasn’t professionally suited up in more than a decade, the Montreal resident puts on his game face almost every day, between running various businesses, coaching soccer, and being a dedicated Dance Dad who “never misses a competition.”

“I’m a present and involved parent whose interests and fun-time revolve around my family,” Gaul says. “I wouldn’t trade these moments for anything.”

His and Malarchuk’s passion for life—and entrepreneurship—is readily apparent to Schmeling, who runs the Syracuse EBV program. “What we’re seeing in the classroom is that there’s not much difference in how Mike and Clint relate to business, compared to that of many of our post-9/11 veterans with disabilities,” he says. “It’s a life-changing experience for Mike and Clint because they have faith in their ability to execute their vision. There’s also a commonality of desire and experience that they have with one another and with the rest of the group.”

Leave it to the skaters to have the final word. “There’s warrior spirit and then there’s cowboy spirit,” interjects Gaul, with a wink and a nod.

“I know,” says Malarchuk, smiling knowingly. “With cowboy spirit, you dust yourself off and get back in the saddle. The ground may not be as soft as it used to be, but, then again, God doesn’t give you what you can’t handle.”