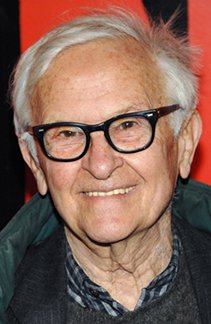

University Mourns Loss of Filmmaker Albert Maysles ’49

Pioneer documentarian known for ‘Gimme Shelter,’ ‘Grey Gardens’

A graduate of Syracuse University’s College of Arts and Sciences, Maysles died on March 5, 2015, at his home in Manhattan. He was 88. According to his daughter Sara, he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a month before his death.

“While we mourn the loss of Albert, we also celebrate his remarkable life and hope that it serves as inspiration to people around the world to be willing to push themselves, creatively, and [to] take the time to observe and reflect on life, as it unfolds,” says Erika Dilday, executive director of the Maysles Documentary Center in Manhattan.

Maysles (pronounced MAY-zuls), along with his late brother, David, is remembered as a pioneer of direct cinema—a documentary genre devoid of scripts, sets, interviews, or narration. Maysles’ more than 50 films include some of the most iconic in documentary history: What’s Happening! The Beatles in the U.S.A. (1964); Salesman (1969); Gimme Shelter (1970); and Grey Gardens (1975), which was later adapted into a Broadway musical and a made-for-TV movie.

Almost no one was too famous—or infamous—to escape Maysles’ keen eye. His subjects ranged from the ordinary, such as a traveling Bible salesman, to the fashionable, including actor Orson Welles, artist Salvador Dali, and boxer Muhammad Ali.

“My life has been like the flight of a bird,” Maysles told a packed room at Manhattan’s St. Regis Hotel, where he was presented in 2006 with the George Arents Pioneer Medal, the University’s highest honor bestowed on alumni (now known as the Arents Award). “It’s been graced with great, great luck and uncertainty and adventure.”

At the same event, filmmaker Martin Scorsese—who had known Maysles since the 1960s and, at one point, briefly worked for him—added: “Everyone knows he’s a ‘pioneer.’ He’s the genuine article.”

Born in Boston to Jewish immigrants, Maysles briefly served in the U.S. Army, before earning degrees in psychology from Syracuse and Boston universities. Initially, he worked as a teacher, but the chance to travel to Russia, at the height of the Cold War, to make a documentary about mental hospitals proved life-changing.

Maysles began training in earnest under Robert Drew, a pioneer of cinéma vérité, which relied heavily on authentic dialogues and naturalness of action. With the advent of portable, lightweight sound and film equipment, Maysles, along with D.A. Pennebaker and Frederick Wiseman, helped usher in direct cinema, the United States’ answer to cinéma vérité.

“When he got a camera against his eye, he was one of the world’s great watchers, and I knew we would always be filmmaking companions,” says Pennebaker, who is perhaps best known for Monterey Pop (1967), on which Maysles served as a camera operator.

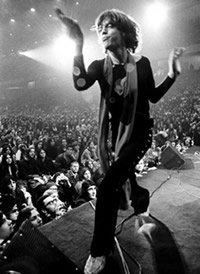

The Maysles brothers’ “observational” approach, known for its delicacy and immediacy, enabled them to capture some of the most defining moments of the latter half of the 20th century. Chief among them was the stabbing of an 18-year-old fan by a Hell’s Angel at a Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Speedway in California, signaling the ideological end of the 1960s’ “peace and love” experiment.

Forty-five years on, the scene in which singer Mick Jagger views the raw footage of the killing still captivates.

“There’s nothing more harrowing than watching Jagger’s reaction, especially when he rewinds the editing machine and replays the murder scene in slow motion,” says David Yaffe, an award-winning author and assistant professor of the humanities in A&S. “There’s also the single, unbroken shot of the Stones listening to a playback of Wild Horses—something that occurred a few days before the murder. It’s eerie and melancholy at the same time.”

Gimme Shelter almost didn’t happen, says Alan Bomser, Maysles’ attorney for more than 40 years, as well as a close friend and confidant. He says that David, who handled the brothers’ business affairs until his death in 1987, initially had trouble finding a distributor.

“The Alameda County District Attorney’s Office demanded copies of the film, so they could prosecute somebody for the murder,” he recalls, speaking by phone from his home in Manhattan. “Meanwhile, David tried to get clearances from the Hell’s Angels for the release of the film. They beat him up, literally stomped on him.”

Says Yaffe: “It’s remarkable to think that, with all the coverage of the Rolling Stones, including films by Jean-Luc Godard and Martin Scorsese, Gimme Shelter is the one we’re still talking about. Maysles was present for the apocalypse at Altamont and made the most of it. He really knew how to capture character.”

Like Gimme Shelter, Grey Gardens had its share of behind-the-scenes drama. Lee Radziwill, the younger sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, initially hired the Maysles to do a family documentary. The family, of course, included Radziwill’s aunt, “Big Edie” Bouvier Beale, and her grown daughter, “Little Edie,” who lived in a run-down mansion called “Grey Gardens.”

The Maysles spent more than two weeks shooting in East Hampton, N.Y., and, in the process, found the Beales to be interesting subjects. Much to Radziwill's dismay, they decided to make a film about them.

“Radziwill demanded a meeting with the Maysles to convince them not to make their own film,” recalls Bomser, who was in attendance, along with renowned photographer Peter Beard and Radziwell’s lawyer, Alan U. Schwartz. “Things got quite heated and ended with Al and David telling her that, notwithstanding her wish, they would make the documentary. So Radziwill didn’t get what she wanted, and a wonderful film was made.”

Maysles was active right up until his death, filming as recently as this past December. He had just completed work on In Transit, a documentary about the United States' longest train route, which is scheduled to premiere next month at the Tribecca Film Festival. His eponymously titled film about fashion icon Iris Apfel, which premiered last fall at the New York Film Festival, opens next month, as well. The long-awaited self-portrait, Handheld and from the Heart, is also in production. More information about these and other related projects is available at mayslesfilms.com.

Maysles reunited with the University more than a decade ago. He gave multiple lectures at New York's Joseph I. Lubin House, which presented various exhibitions of his films, photographs, and equipment.

When grand-scale artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude installed more than 7,000 vinyl “gates” in nearby Central Park in 2005, Maysles was there to film the proceedings, later earning a Peabody Award for his efforts.

Albert (left) and David Maysles

Albert (left) and David MayslesBomser echoes these sentiments. “Al was an angelic presence who knew how to connect with people,” he adds. “He always had that camera on his shoulder, but you never knew if it was turned on or not. That’s how he got his best stuff.”

Maysles’ survivors include his wife of 39 years, Gillian Walker, and his children Rebekah, Philip, Sara, and Auralice.

"My father always engaged with his subjects, although he believed they could be objective at the same time," says Sara, co-author of Grey Gardens (Free News Projects, 2009) and a former Maysles Films archivist. "'Love your subject,' even if you disagree with their actions or beliefs, is something he often repeated to aspiring filmmakers."

Donations in his memory may be sent to the Maysles Documentary Center at 343 Lenox Ave., New York NY 10027.

Media Contact

Ron Enslin