Jack of all trades

Veteran sportswriter, biographer Jack Cavanaugh ’52 reflects on multifaceted career

Jack Cavanaugh ’52 is the first to admit he has a competitive streak. It likely took root at Syracuse University, where he played baseball and basketball as a freshman and where it spread throughout other facets of his life, including his more than 25 years as a sportswriter for The New York Times.

“The competition always made it more fun,” says Cavanaugh, speaking by phone from his home in Stamford, Connecticut. “It was like playing sports. When I started out as a reporter, we always competed with other papers to break a story. We wanted to beat them. It was fun and, depending on the subject matter, kind of glamorous.”

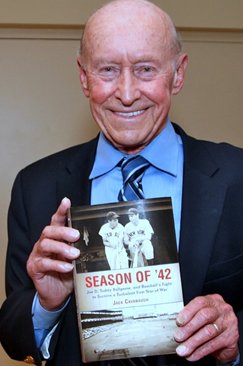

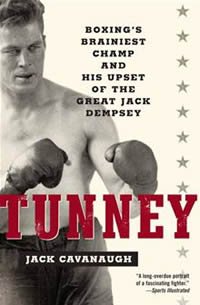

Praised by Sports Illustrated for his “impressively researched and richly detailed” writing, Cavanaugh has parlayed his natural instinct for competition into a hundreds of articles and five critically acclaimed books, including Season of ’42: Joe D., Teddy Ballgame, and Baseball’s Fight to Survive a Turbulent First Year of War (Skyhorse Publishing, 2012); and Tunney: Boxing’s Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey (Random House, 2006), for which he was nominated the Pulitzer Prize in Biography. In addition to SI and Reader’s Digest, Cavanaugh has been a longtime contributor to The Sporting News, Tennis, and Golf magazines; Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine for United Airlines; and the Chicken Soup for the Soul book series. He also writes a twice-monthly column for his hometown newspaper, The Stamford Advocate.

After a stint in the U.S. Navy, Cavanaugh began his journalism career at The New Haven Register. There in the 1950s, amid the so-called “Golden Age of Journalism,” he took whatever his “gruff editor with a heart of gold” assigned him. Cavanaugh proved to be a quick study, and his penchant for accuracy and storytelling eventually led him to the pinnacle of the profession: a staff position at The New York Times.

“Although I liked sports, I didn’t want to be stamped as a sportswriter,” he says. “So at The Times, I did a lot of feature writing, as well as reporting for just about every other section of the paper. It was a good way to earn extra money and was perfectly legitimate.”

Since leaving The Times in 2005, Cavanaugh has concentrated on book writing and teaching. He has held faculty positions at Fairfield and Quinnipiac universities in Connecticut and at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

“Notice things, and be curious,” says Cavanaugh, who has lectured in The Writing Program in SU’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Some of the best writers focus on things that haven’t been done before. Never stop writing.”

The following is from a discussion between Cavanaugh (JC) and The College (A&S):

“The competition always made it more fun,” says Cavanaugh, speaking by phone from his home in Stamford, Connecticut. “It was like playing sports. When I started out as a reporter, we always competed with other papers to break a story. We wanted to beat them. It was fun and, depending on the subject matter, kind of glamorous.”

Praised by Sports Illustrated for his “impressively researched and richly detailed” writing, Cavanaugh has parlayed his natural instinct for competition into a hundreds of articles and five critically acclaimed books, including Season of ’42: Joe D., Teddy Ballgame, and Baseball’s Fight to Survive a Turbulent First Year of War (Skyhorse Publishing, 2012); and Tunney: Boxing’s Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey (Random House, 2006), for which he was nominated the Pulitzer Prize in Biography. In addition to SI and Reader’s Digest, Cavanaugh has been a longtime contributor to The Sporting News, Tennis, and Golf magazines; Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine for United Airlines; and the Chicken Soup for the Soul book series. He also writes a twice-monthly column for his hometown newspaper, The Stamford Advocate.

After a stint in the U.S. Navy, Cavanaugh began his journalism career at The New Haven Register. There in the 1950s, amid the so-called “Golden Age of Journalism,” he took whatever his “gruff editor with a heart of gold” assigned him. Cavanaugh proved to be a quick study, and his penchant for accuracy and storytelling eventually led him to the pinnacle of the profession: a staff position at The New York Times.

“Although I liked sports, I didn’t want to be stamped as a sportswriter,” he says. “So at The Times, I did a lot of feature writing, as well as reporting for just about every other section of the paper. It was a good way to earn extra money and was perfectly legitimate.”

Since leaving The Times in 2005, Cavanaugh has concentrated on book writing and teaching. He has held faculty positions at Fairfield and Quinnipiac universities in Connecticut and at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

“Notice things, and be curious,” says Cavanaugh, who has lectured in The Writing Program in SU’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Some of the best writers focus on things that haven’t been done before. Never stop writing.”

The following is from a discussion between Cavanaugh (JC) and The College (A&S):

A&S: You majored in political science [in The College of Arts and Sciences], yet you wrote for The Daily Orange and took journalism classes at Yates Castle on Crouse Avenue. It sounds as though the combination of the liberal arts and a professional education had a big effect on you.

JC: I owe a lot to the journalism dean [Wesley Clark], who must of thought I was a fairly good writer because he steered me toward a couple of newspapers. One of them was The Watertown Daily Times. For a small town in New York, Watertown had a good newspaper. I wrote for The Daily Orange occasionally and had some clippings of my work to show them. Any good reporter will tell you that when you [interview] for a job, editors could care less if you have a Ph.D. They just want to see what you've written.

A&S: And where you’ve written it.

JC: Right. So I was offered the job in Watertown. But after four years of the cold and snow in Syracuse, I didn’t want to go 80 miles north. I told the editor I had an opportunity to work in New Haven, which was about 35 miles from my home in Stamford. I had been away for six years—two in the Navy and four at SU---so he understood.

I worked for The New Haven Register for two years and got to cover everything. I was pretty ambitious. From there, I went to the Providence Journal in Rhode Island and then to United Press International in Hartford, where I also briefly attended the University of Connecticut School of Law, since I had found myself covering so many court cases and dealing with judges. UPI eventually transferred me to New York, where I spent the next three years, before going to Washington, D.C.

After being a bachelor in New York, my four months in Washington were something of a disappointment, since it seemed that everywhere I went, all that people talked about was politics. It was kind of boring. I started going back to New York on the weekends and then wound up back there for good.

In New York, I worked at the Journal-American [which folded in 1966] and then at ABC News, where I met my wife, Marge. After six years at ABC, I went to CBS News for two years. It was a good time to be a reporter in New York, since I got to cover a lot of the racial unrest going on at the time, including riots in Harlem and Newark, along with many huge anti-Vietnam War demonstrations.

Keep in mind that at ABC and CBS, I was a reporter who did general news, but along the way, I started doing some sports. For instance, I’d cover the occasional NFL game, doing post-game interviews, or I’d cover something at the old Yankee Stadium [in the South Bronx]. My desire to do more sportswriting eventually led to work with Reuters in New York as a news correspondent and sportswriter and then to The New York Times.

A&S: What was the newsroom like in those days?

JC: The scene at The New Haven Register was right out of a “B” movie. There was a lot of noise. Everybody was using typewriters. Most of the reporters smoked. And there were people calling out for copy boys. Everybody was fighting deadlines. I loved it.

A&S: It sounds very romantic.

JC: It was. Nowadays, you go into a newsroom, and it’s like walking into a bank. It’s very quiet. You no longer hear the sounds of the typewriter or Teletype machine, with news coming off the wire. It’s totally different.

A&S: What was the competition like among papers?

JC: In New Haven, you had two newspapers, both in the same building and with the same owner, but they were competitors. The fact you had competition wherever you went—a lot of places were two-newspaper markets owned by the same person—was great. Today, unless you’re in a big market such as New York or Chicago, there’s virtually no competition among papers.

A&S: Was journalism still an an "old boys club”?

JC: Not entirely, but that’s a good question. In New Haven, the morning paper had a young society editor in her 20s, and the evening paper had a society editor in her 40s. They were the only women on staff, and look at what they were doing. They weren't exactly covering "hard news." Providence had a few more female staff writers, but it was still very much an “old boys” network.

A&S: What was the quality of reporting and writing like then?

JC: With all the competition in each market, the quality [of journalism] was good. But today—at a time when newspapers are really hurting—the writing, ironically, has never been better.

After Syracuse, I wound up working with some people who were much better writers than I, even though, in many cases, they had never gone to college. Many of them had started out after high school as copy boys and had learned to write on the job. Some of them wrote well, although the writing back then was mostly flamboyant and florid, with a lot of hyperbole.

That said, many of the columnists at the time were as good as today’s columnists, if not better, with more distinctive styles. That’s because they were good reporters, which made them good writers. In general, newspaper and magazine writing is better today than it was, say, 30, 40, 50 years ago.

Another thing about today is that reporters, for the most part, are younger. Once you reach 50, you're apt to be asked to take a buy-out, retire, and be replaced by a younger person at the bottom of the pay-scale. Many large papers today, including The Times, use young freelancers to save money.

A&S: What’s the difference between writing and reporting?

JC: A reporter is someone who collects facts, while a writer, who can also be a reporter, puts those facts into words. To be a good writer, you have to be a good reporter. With book writing, something I devote most of my time to now, my experience as a reporter has helped me tremendously as an author. Covering a beat, I think, makes you a better writer.

I tell students that to be a good writer or reporter you have to be a good reader. I don’t know how many times I’ve been told that I was born a good writer. Nonsense! I learned how to write. As a newspaper delivery boy, I was so into sports that I couldn’t wait to get The New York Daily News in the morning and devour the sports section. Before long, I also started reading the news section in other papers that I delivered on my bike before and after school. I'm sure that all of that early reading helped me as a writer, especially later on, when I wrote for my junior high and high school newspapers and for The Daily Orange.

At Syracuse, I began reading Damon Runyon and Ring Lardner, both wonderful sportswriters who became very good short-story writers. I was inspired by them, knowing they had been sportswriters but could write about non-sporting events in a humorous and entertaining way.

Years later, I got to know Budd Schulberg, who gave me a wonderful blurb for my Gene Tunney book. Budd wrote several great novels, including What Makes Sammy Run? and The Harder They Fall, as well as the screenplay for On the Waterfront. Budd was not a full-time sportswriter, but he could cover sports. He was one of my most favorite writers.

A&S: You’ve interviewed many celebrities over the years. Any of them stand out?

JC: I remember interviewing Richard Nixon in 1967, just as he was about to announce his second bid for the presidency. I didn’t particularly care for his politics, but I found him to be surprisingly friendly and gracious during a one-on-one interview. Nixon understood the power of the media. I was working for CBS at the time, and during the interview, he indicated that he would seek the Republican nomination again. I had myself a scoop of sorts.

Probably my all-time favorite subject was former President Harry Truman. As a young reporter in New York, I was often assigned to accompany him on his famous early morning walks along Madison Avenue, when he was visiting his daughter, Margaret; his son-in-law, Clifton Daniel, a top New York Times editor; and his grandchildren. Truman was a delight, and he didn’t hesitate to answer questions of a sometimes delicate nature about his presidency.

During the late ’50s and early ‘60s, Truman usually walked from the Carlyle Hotel to Rockefeller Center, a distance of about 25 blocks. Getting to know him up close was special to me. Once during a surprise breakfast stop at a popular restaurant on Madison Avenue, Truman told me that if you really want to know American history, you should read about its presidents--something he had done as a young man. Though Truman was often derided while in office, he is regarded today as one of our top-10 presidents.

A&S: When did you start writing books?

JC: During my days as a writer and reporter, I had never given any thought toward writing a book. But when I was at ABC, I used to go the [West Side] YMCA on West 63rd Street and play basketball during lunchtime or after work. The players there were pretty good, and our games were rather competitive.

One day, I played against a guy with only one arm. He turned out to be terrific. He could dribble, shoot, rebound—all with one arm. I never forgot him. Years later, I read about a one-armed baseball player named Pete Gray, who played in the major leagues during 1945. After that, I saw a photo caption in a newspaper about a high school football player in Chicago with no arms. Then I heard about a kid playing Little League who had lost both hands. He played with a special glove and had a prosthetic on the other hand. I began to think there was a book there. The result was Damn the Disabilities: Full Speed Ahead [WRS Publishing, 1995].

A&S: What about Season of ’42?

JC: It was a crucial year in American history and in World War II. There were blackouts, dim-outs, threats of attack by the Japanese, particularly in California. Everything seemed to be going wrong for us in the American Pacific. The Japanese had a huge edge on us and were better prepared for war than we were.

It was also an unusual time for baseball. Following the 1942 season, stars such as Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Phil Rizzuto would be drafted into service, not to return until 1946. All hell was breaking loose, as everyone seemed to join the war effort and defense plants were booming.

A&S: Why was it important for baseball to continue during the war?

JC: The first commissioner of baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, wrote President Roosevelt during the winter of ’42, asking if it was proper for the sport to continue with the war going on. The result was Roosevelt’s famous “Green Light Letter,” in which he said it would be “best for the country” to keep baseball going. He felt the game would be a good diversion for not only American defense workers, but also GIs stationed abroad. Baseball was a way for people to relax and get their minds off the war.

A&S: I imagine this topic resonated with you, since you played sports at SU.

JC: Well, SU wasn't the best place to play baseball because of the weather. You were lucky to get in half of your scheduled games because of the snow; cold weather; and soggy, wet playing fields.

One of my best memories of SU actually took place off the field. In those days, many of us, including Jack Kiley [‘51], who went on to play for the NBA, waited tables at Winchell Hall at a time when female students from nearby cottages ate there. The best part of that job, without a doubt, was that Winchell was an all-girls’ dining hall. In addition to having my meals taken care of, it certainly was a great way to meet girls. Almost all of those jobs were held by athletes as part of their scholarships or because they had work in the off-season to earn room and board. It was probably the best job I ever had.

A&S: Better than interviewing Nixon?

JC: Much better, but in a different context.

JC: I owe a lot to the journalism dean [Wesley Clark], who must of thought I was a fairly good writer because he steered me toward a couple of newspapers. One of them was The Watertown Daily Times. For a small town in New York, Watertown had a good newspaper. I wrote for The Daily Orange occasionally and had some clippings of my work to show them. Any good reporter will tell you that when you [interview] for a job, editors could care less if you have a Ph.D. They just want to see what you've written.

A&S: And where you’ve written it.

JC: Right. So I was offered the job in Watertown. But after four years of the cold and snow in Syracuse, I didn’t want to go 80 miles north. I told the editor I had an opportunity to work in New Haven, which was about 35 miles from my home in Stamford. I had been away for six years—two in the Navy and four at SU---so he understood.

I worked for The New Haven Register for two years and got to cover everything. I was pretty ambitious. From there, I went to the Providence Journal in Rhode Island and then to United Press International in Hartford, where I also briefly attended the University of Connecticut School of Law, since I had found myself covering so many court cases and dealing with judges. UPI eventually transferred me to New York, where I spent the next three years, before going to Washington, D.C.

After being a bachelor in New York, my four months in Washington were something of a disappointment, since it seemed that everywhere I went, all that people talked about was politics. It was kind of boring. I started going back to New York on the weekends and then wound up back there for good.

In New York, I worked at the Journal-American [which folded in 1966] and then at ABC News, where I met my wife, Marge. After six years at ABC, I went to CBS News for two years. It was a good time to be a reporter in New York, since I got to cover a lot of the racial unrest going on at the time, including riots in Harlem and Newark, along with many huge anti-Vietnam War demonstrations.

Keep in mind that at ABC and CBS, I was a reporter who did general news, but along the way, I started doing some sports. For instance, I’d cover the occasional NFL game, doing post-game interviews, or I’d cover something at the old Yankee Stadium [in the South Bronx]. My desire to do more sportswriting eventually led to work with Reuters in New York as a news correspondent and sportswriter and then to The New York Times.

A&S: What was the newsroom like in those days?

JC: The scene at The New Haven Register was right out of a “B” movie. There was a lot of noise. Everybody was using typewriters. Most of the reporters smoked. And there were people calling out for copy boys. Everybody was fighting deadlines. I loved it.

A&S: It sounds very romantic.

JC: It was. Nowadays, you go into a newsroom, and it’s like walking into a bank. It’s very quiet. You no longer hear the sounds of the typewriter or Teletype machine, with news coming off the wire. It’s totally different.

A&S: What was the competition like among papers?

JC: In New Haven, you had two newspapers, both in the same building and with the same owner, but they were competitors. The fact you had competition wherever you went—a lot of places were two-newspaper markets owned by the same person—was great. Today, unless you’re in a big market such as New York or Chicago, there’s virtually no competition among papers.

A&S: Was journalism still an an "old boys club”?

JC: Not entirely, but that’s a good question. In New Haven, the morning paper had a young society editor in her 20s, and the evening paper had a society editor in her 40s. They were the only women on staff, and look at what they were doing. They weren't exactly covering "hard news." Providence had a few more female staff writers, but it was still very much an “old boys” network.

A&S: What was the quality of reporting and writing like then?

JC: With all the competition in each market, the quality [of journalism] was good. But today—at a time when newspapers are really hurting—the writing, ironically, has never been better.

After Syracuse, I wound up working with some people who were much better writers than I, even though, in many cases, they had never gone to college. Many of them had started out after high school as copy boys and had learned to write on the job. Some of them wrote well, although the writing back then was mostly flamboyant and florid, with a lot of hyperbole.

That said, many of the columnists at the time were as good as today’s columnists, if not better, with more distinctive styles. That’s because they were good reporters, which made them good writers. In general, newspaper and magazine writing is better today than it was, say, 30, 40, 50 years ago.

Another thing about today is that reporters, for the most part, are younger. Once you reach 50, you're apt to be asked to take a buy-out, retire, and be replaced by a younger person at the bottom of the pay-scale. Many large papers today, including The Times, use young freelancers to save money.

A&S: What’s the difference between writing and reporting?

JC: A reporter is someone who collects facts, while a writer, who can also be a reporter, puts those facts into words. To be a good writer, you have to be a good reporter. With book writing, something I devote most of my time to now, my experience as a reporter has helped me tremendously as an author. Covering a beat, I think, makes you a better writer.

I tell students that to be a good writer or reporter you have to be a good reader. I don’t know how many times I’ve been told that I was born a good writer. Nonsense! I learned how to write. As a newspaper delivery boy, I was so into sports that I couldn’t wait to get The New York Daily News in the morning and devour the sports section. Before long, I also started reading the news section in other papers that I delivered on my bike before and after school. I'm sure that all of that early reading helped me as a writer, especially later on, when I wrote for my junior high and high school newspapers and for The Daily Orange.

At Syracuse, I began reading Damon Runyon and Ring Lardner, both wonderful sportswriters who became very good short-story writers. I was inspired by them, knowing they had been sportswriters but could write about non-sporting events in a humorous and entertaining way.

Years later, I got to know Budd Schulberg, who gave me a wonderful blurb for my Gene Tunney book. Budd wrote several great novels, including What Makes Sammy Run? and The Harder They Fall, as well as the screenplay for On the Waterfront. Budd was not a full-time sportswriter, but he could cover sports. He was one of my most favorite writers.

A&S: You’ve interviewed many celebrities over the years. Any of them stand out?

JC: I remember interviewing Richard Nixon in 1967, just as he was about to announce his second bid for the presidency. I didn’t particularly care for his politics, but I found him to be surprisingly friendly and gracious during a one-on-one interview. Nixon understood the power of the media. I was working for CBS at the time, and during the interview, he indicated that he would seek the Republican nomination again. I had myself a scoop of sorts.

Probably my all-time favorite subject was former President Harry Truman. As a young reporter in New York, I was often assigned to accompany him on his famous early morning walks along Madison Avenue, when he was visiting his daughter, Margaret; his son-in-law, Clifton Daniel, a top New York Times editor; and his grandchildren. Truman was a delight, and he didn’t hesitate to answer questions of a sometimes delicate nature about his presidency.

During the late ’50s and early ‘60s, Truman usually walked from the Carlyle Hotel to Rockefeller Center, a distance of about 25 blocks. Getting to know him up close was special to me. Once during a surprise breakfast stop at a popular restaurant on Madison Avenue, Truman told me that if you really want to know American history, you should read about its presidents--something he had done as a young man. Though Truman was often derided while in office, he is regarded today as one of our top-10 presidents.

A&S: When did you start writing books?

JC: During my days as a writer and reporter, I had never given any thought toward writing a book. But when I was at ABC, I used to go the [West Side] YMCA on West 63rd Street and play basketball during lunchtime or after work. The players there were pretty good, and our games were rather competitive.

One day, I played against a guy with only one arm. He turned out to be terrific. He could dribble, shoot, rebound—all with one arm. I never forgot him. Years later, I read about a one-armed baseball player named Pete Gray, who played in the major leagues during 1945. After that, I saw a photo caption in a newspaper about a high school football player in Chicago with no arms. Then I heard about a kid playing Little League who had lost both hands. He played with a special glove and had a prosthetic on the other hand. I began to think there was a book there. The result was Damn the Disabilities: Full Speed Ahead [WRS Publishing, 1995].

A&S: What about Season of ’42?

JC: It was a crucial year in American history and in World War II. There were blackouts, dim-outs, threats of attack by the Japanese, particularly in California. Everything seemed to be going wrong for us in the American Pacific. The Japanese had a huge edge on us and were better prepared for war than we were.

It was also an unusual time for baseball. Following the 1942 season, stars such as Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Phil Rizzuto would be drafted into service, not to return until 1946. All hell was breaking loose, as everyone seemed to join the war effort and defense plants were booming.

A&S: Why was it important for baseball to continue during the war?

JC: The first commissioner of baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, wrote President Roosevelt during the winter of ’42, asking if it was proper for the sport to continue with the war going on. The result was Roosevelt’s famous “Green Light Letter,” in which he said it would be “best for the country” to keep baseball going. He felt the game would be a good diversion for not only American defense workers, but also GIs stationed abroad. Baseball was a way for people to relax and get their minds off the war.

A&S: I imagine this topic resonated with you, since you played sports at SU.

JC: Well, SU wasn't the best place to play baseball because of the weather. You were lucky to get in half of your scheduled games because of the snow; cold weather; and soggy, wet playing fields.

One of my best memories of SU actually took place off the field. In those days, many of us, including Jack Kiley [‘51], who went on to play for the NBA, waited tables at Winchell Hall at a time when female students from nearby cottages ate there. The best part of that job, without a doubt, was that Winchell was an all-girls’ dining hall. In addition to having my meals taken care of, it certainly was a great way to meet girls. Almost all of those jobs were held by athletes as part of their scholarships or because they had work in the off-season to earn room and board. It was probably the best job I ever had.

A&S: Better than interviewing Nixon?

JC: Much better, but in a different context.

Media Contact

Rob Enslin