The art of science; the science of art

Chemistry department glassblower fuses art and science in her work

The shelves, drawers, nooks, and crannies of Sally Prasch’s laboratory in the basement of Syracuse University’s Center for Science and Technology are packed with a myriad of glass items—round and square rods, tubes, connectors, valves, stopcocks, ampules, and more—from the miniscule to the very large.

To the casual observer, the glass pieces seem unyielding, yet Prasch will bend, twist, shape, and fuse the material in seemingly impossible ways. She creates customized scientific glassware for researchers in the Department of Chemistry in SU’s College of Arts and Sciences and sometimes for others across campus for experiments requiring highly specialized apparatuses that are not readily available from commercial suppliers.

“Often I have to develop an apparatus for an experiment,” Prasch says. “To do that, I work with the scientists to understand their experiment and what they want the glass to do.” Prasch recalls one project that required revisions and redesigns over a period of nearly four years to get the apparatus to the point where it worked efficiently for the experiment. “Our first designs would implode 20 seconds into the experiment,” she says. “We finally got to the point where the apparatus would last for two months without imploding.”

In the world of scientific glassblowing, Prasch is a member of a shrinking fraternity, according to a 2006 article in Chemical and Engineering News. The American Scientific Glassblowers Society lists just 650 members from across the country on its web site. Many train at Salem Community College in New Jersey, the only school in the country that grants degrees in scientific glass technology. Prasch holds both a certificate in scientific glass technology and an associate’s degree in applied science from the school.

To the casual observer, the glass pieces seem unyielding, yet Prasch will bend, twist, shape, and fuse the material in seemingly impossible ways. She creates customized scientific glassware for researchers in the Department of Chemistry in SU’s College of Arts and Sciences and sometimes for others across campus for experiments requiring highly specialized apparatuses that are not readily available from commercial suppliers.

“Often I have to develop an apparatus for an experiment,” Prasch says. “To do that, I work with the scientists to understand their experiment and what they want the glass to do.” Prasch recalls one project that required revisions and redesigns over a period of nearly four years to get the apparatus to the point where it worked efficiently for the experiment. “Our first designs would implode 20 seconds into the experiment,” she says. “We finally got to the point where the apparatus would last for two months without imploding.”

In the world of scientific glassblowing, Prasch is a member of a shrinking fraternity, according to a 2006 article in Chemical and Engineering News. The American Scientific Glassblowers Society lists just 650 members from across the country on its web site. Many train at Salem Community College in New Jersey, the only school in the country that grants degrees in scientific glass technology. Prasch holds both a certificate in scientific glass technology and an associate’s degree in applied science from the school.

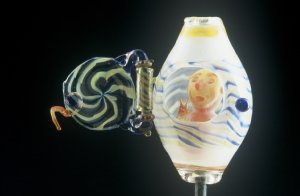

Even as Prasch is a member of an increasingly rare breed of scientific glassblowers, what’s rarer still is how she fuses science and art in her professional life. She is internationally renowned for her artistic glass, which she creates in a private studio near Springfield, Mass. Her exquisite sculptures have been exhibited in galleries and museums across the United States as well as internationally. Her work is also featured in a number of books and magazine articles, including The Penland Book of Glass: Master Classes in Flamework Technique (Lark Books, 2009) and 500 Glass Objects: A Celebration of Functional and Sculptural Glass (Lark Books, 2006).

“I don’t see a big difference between artists and scientists,” Prasch says. “Both are reaching for the unknown. They need to open and expand their minds in order to achieve their desired results. I couldn’t do my artwork without my scientific skills, nor could I do my scientific work without my artistic skills.”

Prasch holds a bachelor’s degree in fine art in glass and ceramics from the University of Kansas and is passionate about teaching both the scientific and artistic sides of her craft. Her specialty is flameworking and her tools of choice are hand-held gas torches of varying sizes. She also uses a glassblower’s lathe, which can hold glass items that are too large to be held by hand. Prasch has taught flameworking at SU; the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; and the University of Michigan, Dearborn. She is frequently invited to teach masters-level workshops in different forms of glassmaking at some of the most exclusive artisan schools and studios across the country and around the world, including the Niijima Glass School in Japan; Snow Farm in Williamsburg, Mass.; Pilchuck Glass School, Washington; and the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina.

Prasch was recently an invited guest at Penland’s acclaimed Retreat for Teaching Artists. Held in September, the retreat was supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. In December, she will travel to Japan to teach masters-level workshops in Tokyo and Kobe, and next spring she will teach a weeklong workshop in Ireland at the famed Essence of Mulranny, known as an artist’s paradise.

There’s a story behind almost every piece of glass Prasch creates, whether she is creating an apparatus for a scientist or a sculpture, which emerges as a visible expression of her emotions, thoughts, and experiences. “I think we are all artists and need to express ourselves,” she says.

Prasch created “Bouncing Goblets” in honor of her parents’ 50th wedding anniversary. The stems are made of flexible glass coils, similar to the coils she creates for condensers in the chemistry labs. She says the goblets will bounce off the table if one is not careful. “I figured my parents had to be pretty flexible to be married that long,” she says.

“Open for Peace,” which was created after 9/11, is an inch-high sculpture with a hinged door that opens to reveal a tiny person flashing the peace sign. “Baby” is a bubble made from uranium glass and filled with xenon gas. It was created in celebration of friends who were expecting a baby. “My Father’s Face, My Face” emerged after her father’s death. “I am my father’s daughter,” Prasch says. “He lives through me and the people who were in his life.”

“I don’t see a big difference between artists and scientists,” Prasch says. “Both are reaching for the unknown. They need to open and expand their minds in order to achieve their desired results. I couldn’t do my artwork without my scientific skills, nor could I do my scientific work without my artistic skills.”

Prasch holds a bachelor’s degree in fine art in glass and ceramics from the University of Kansas and is passionate about teaching both the scientific and artistic sides of her craft. Her specialty is flameworking and her tools of choice are hand-held gas torches of varying sizes. She also uses a glassblower’s lathe, which can hold glass items that are too large to be held by hand. Prasch has taught flameworking at SU; the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; and the University of Michigan, Dearborn. She is frequently invited to teach masters-level workshops in different forms of glassmaking at some of the most exclusive artisan schools and studios across the country and around the world, including the Niijima Glass School in Japan; Snow Farm in Williamsburg, Mass.; Pilchuck Glass School, Washington; and the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina.

Prasch was recently an invited guest at Penland’s acclaimed Retreat for Teaching Artists. Held in September, the retreat was supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. In December, she will travel to Japan to teach masters-level workshops in Tokyo and Kobe, and next spring she will teach a weeklong workshop in Ireland at the famed Essence of Mulranny, known as an artist’s paradise.

There’s a story behind almost every piece of glass Prasch creates, whether she is creating an apparatus for a scientist or a sculpture, which emerges as a visible expression of her emotions, thoughts, and experiences. “I think we are all artists and need to express ourselves,” she says.

Prasch created “Bouncing Goblets” in honor of her parents’ 50th wedding anniversary. The stems are made of flexible glass coils, similar to the coils she creates for condensers in the chemistry labs. She says the goblets will bounce off the table if one is not careful. “I figured my parents had to be pretty flexible to be married that long,” she says.

“Open for Peace,” which was created after 9/11, is an inch-high sculpture with a hinged door that opens to reveal a tiny person flashing the peace sign. “Baby” is a bubble made from uranium glass and filled with xenon gas. It was created in celebration of friends who were expecting a baby. “My Father’s Face, My Face” emerged after her father’s death. “I am my father’s daughter,” Prasch says. “He lives through me and the people who were in his life.”

Media Contact

Judy Holmes