Failed Supernova, Cosmic Fireworks

Key Takeaways

- A supernova that fizzled: The Pa 30 remnant can be traced back to a dying star seen in China and Japan in 1181 Common Era (CE) that didn’t completely explode.

- Wind-carved cosmic filaments: After the partial explosion, a dense wind pushed into surrounding gas, creating a rare stellar design.

- Clues to failed explosions: This research suggests that these unusual remnants could be more common than astronomers once thought.

- Terrestrial parallels in nuclear tests: Photographs from 1962 Los Alamos high-altitude nuclear explosions show the formation of similar filamentary structures.

Nearly 900 years ago, skywatchers in China and Japan recorded a brilliant “guest star” that appeared suddenly and lingered in the night sky for six months. Scientists now believe that a recently discovered faint remnant, known as Pa 30, traces back to that event: an incomplete supernova explosion that produced the temporary, luminous outburst observed in 1181.

Supernova explosions, which mark a star’s final moments, typically fall into two main categories:

- Core-collapse supernovae: These occur when a massive star—with at least ten times the mass of our Sun—runs out of nuclear fuel. Its core collapses under gravity, triggering a catastrophic explosion.

- Type Ia supernovae: These represent the detonation of a white dwarf and require a binary system—two stars orbiting a common center. The explosion can be generated by the merger of two white dwarfs (when the binary consists of two white dwarfs), or by accreting material from a companion star (when the binary consists of a white dwarf and an ordinary star), steadily increasing its mass until it detonates.

A new analysis, however, shows that Pa 30 is the remnant of a rarer event—one in which a star began to explode, but failed to do so completely.

“The conditions were not right to yield a successful detonation, or terminal explosion, of the star,” says Eric Coughlin, assistant professor of physics at Syracuse University’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Instead, it burned heavier elements near its surface layers, without fully destroying it. The nuclear burning didn’t transition into a supersonic detonation.” Coughlin’s findings are published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the premier journal for rapid publication of high-impact astronomical research.

When a type-Ia supernova occurs, typically one or both stars are completely destroyed, generating an expanding cloud of debris – known as a supernova remnant – that displays a cauliflower-like structure.

But instead of a thick, chaotic debris cloud, Pa 30 displays long, straight filaments radiating from a central core—like the trails of a firework. The new analysis led by Coughlin helps explain why.

A Supernova Fails to Complete the Job

Astronomers have struggled to understand how Pa 30’s thin, uniform filaments formed. Researchers examined the remnant with modern telescopes, ran simulations and tested multiple scenarios before arriving at a new explanation.

“Supernovae are typically only bright for approximately the first few months after we first detect them, but the remnant is observable by powerful telescopes for hundreds of years afterward as it cools,” says Coughlin.

The study suggests that the initial blast observed in 1181 was unusually weak, allowing one surviving, likely hyper-massive, white dwarf to remain intact at the center. The explosion didn’t create the filaments of Pa 30: they formed afterward. Following the failed detonation, the surviving white dwarf began launching a fast, dense wind enriched with heavy elements forged during the partial blast. This wind is observed today, moving at roughly 15,000 kilometers per second, or 5% the speed of light.

The wind slammed into the lighter gas surrounding the star. At the boundary between the dense wind and the light gas, conditions were right for the Rayleigh–Taylor instability—a process in which a heavier fluid (in this case the wind) pushes into a lighter one—to operate, forming long, finger-like plumes. In Pa 30, those plumes became linear, highly elongated filaments.

What happened next is also unusual. Normally, a second process—the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability, which is the mixing and shearing mechanism that makes smoke curls twist apart—would tear those long fingers to shreds. But in the case of Pa 30, the mixing and shearing never took hold. The dense wind was so much heavier than the gas that the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability was suppressed. As a result, the filaments kept stretching outward as the wind continued to feed them.

Pa 30 was left with an empty central cavity and a halo of filaments that continued expanding. Simulations suggest that a high-density contrast is conducive to the formation of such filamentary structures, but the authors intend to perform a more detailed numerical investigation in future work.

A Rare Remnant—and a Sign There May be More

Coughlin and his colleagues suspect Pa 30 isn’t unique. This kind of failed explosion is rare but increasingly recognized as a distinct subclass of stellar explosion. Astronomers classify them as type-Iax supernovae, an unusual subgroup that represents a different form of stellar death.

“These types of filamentary structures could be present in other astrophysical phenomena that host dense winds, such as tidal disruption events, which occur when a star is destroyed by the gravitational field of a supermassive black hole,” says Coughlin.

Pa 30 is one of the few cases where modern astrophysical modeling can be directly linked to an event recorded by observers nearly 900 years ago. The “guest star” of 1181 CE has become a detailed cosmic case study, revealing how some stars die not in a single cataclysmic blast, but in a complex process that leaves behind surprising structures.

Terrestrial Evidence

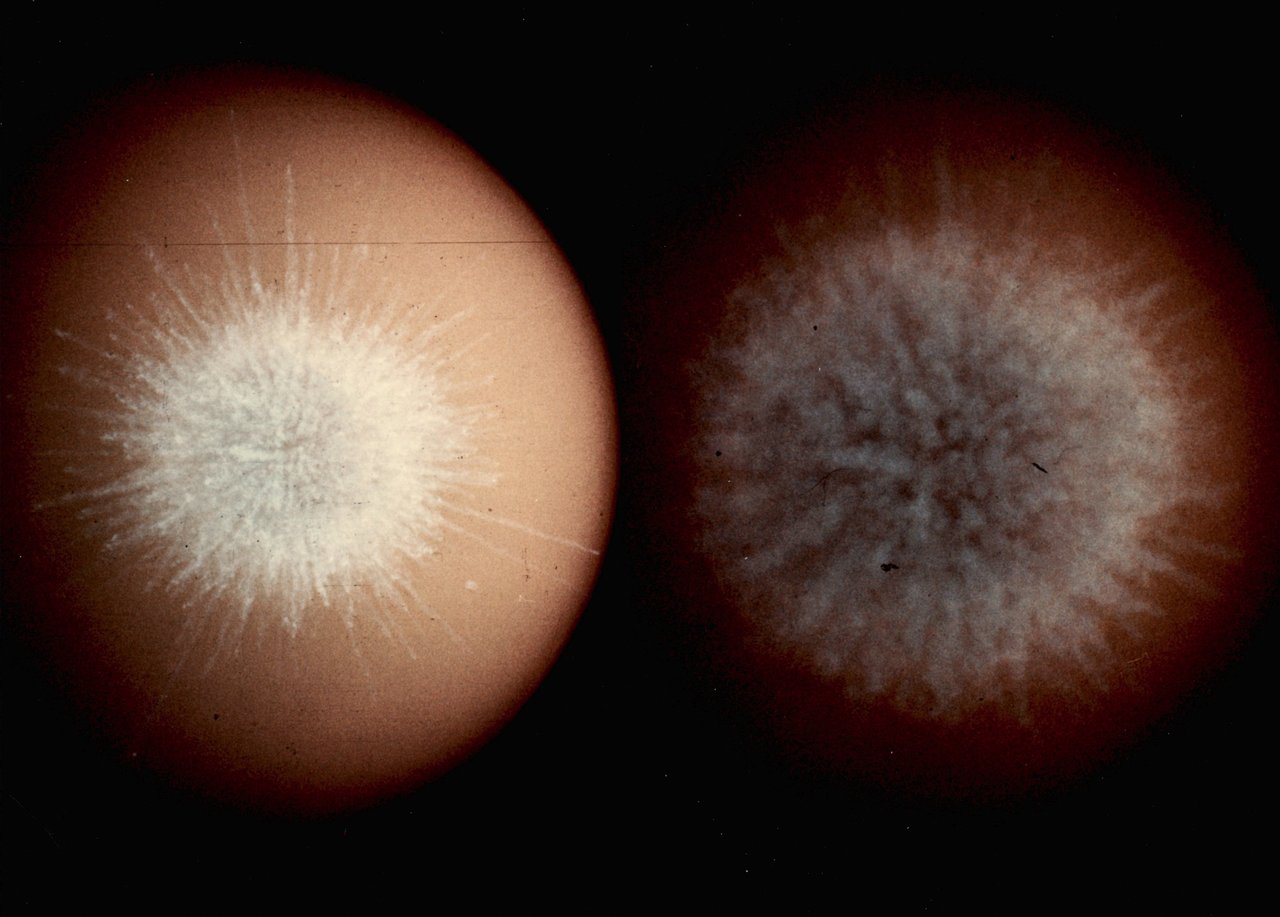

While there are no other known astrophysical sources that display the firework-like morphology of Pa 30, recently released documents from the Los Alamos National Lab (LANL) demonstrate that such structures can arise in terrestrial explosions. Shown below are two photographs from the “Kingfish” high-altitude nuclear test carried out by LANL in 1962. Kingfish was part of Operation Fishbowl, a series of experiments designed to monitor the effects of high-altitude nuclear detonations on military communications, radar systems and missile detection capabilities during the Cold War. The left image highlights the radial tendrils that have formed following the initial explosion, while the right image demonstrates that those same tendrils have morphed into a cauliflower-like structure.

The Kingfish nuclear bomb was similar to typical astrophysical explosions, where a fixed amount of mass and energy is impulsively injected into a gaseous medium; this contrasts the wind-fed origin of the Pa 30 remnant, where energy and momentum were continuously supplied as the material expanded. The fact that the Kingfish experiment initially yielded ejecta that resembled Pa 30 – and later morphed into a structure that is reminiscent of most other supernova remnants –suggests that other non-wind-fed astrophysical explosions may go through this same phase, though it lasts a comparatively short time.

Published: Dec. 23, 2025

Media Contact: asnews@syr.edu