A Moral Vision of Science

Physicist Joel L. Lebowitz G’55, G’56, H’12 believes science and morality are inextricably linked

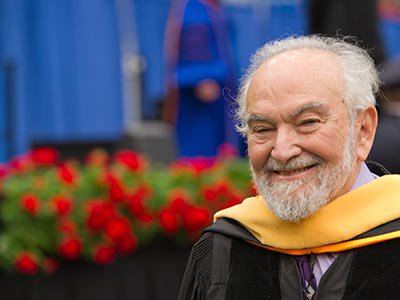

Joel L. Lebowitz G’55, G’56, H’12 credits his longevity to luck and good genes. “I’ve always had a healthy constitution,” says the 88-year-old scientist and Holocaust survivor, who is the George William Hill Professor of Mathematics and Physics at Rutgers University.

Born and raised in Central Europe, Lebowitz narrowly escaped the Auschwitz gas chambers to settle in the United States, where he earned degrees from Brooklyn College and Syracuse University. Lebowitz spent the first two years of his professorial career at Stevens Institute of Technology, followed by 18 years at Yeshiva University.

In addition to his scientific work, Lebowitz has taken up the cause of oppressed scientists around the world. Through his leadership of such organizations as the Committee of Concerned Scientists and the New York Academy of Sciences, he has put pressure on the former Soviet Union to respect human rights agreements.

Along the way, the New Jersey resident has published more than 600 research papers, and has a cornucopia of science awards, including the Boltzmann, Max Planck and Poincare prizes, as well as an extremely selective membership in the National Academy of Sciences.

The College of Arts and Sciences recently caught up with Lebowitz to discuss his multifaceted life and career.

I recall you being honored at Syracuse's 2012 Commencement ceremony, where filmmaker Aaron Sorkin [’83, H’12] told the audience that decisions are made by those who show up.

He was right, you know. I have devoted much time to exploring the moral and social responsibilities of scientists. While the problems facing us today are different from, say, the Nazi period, the basic moral issues are unchanged; in fact, they are eternal.

Syracuse gave me an excellent education. It was there, under the guidance of my thesis adviser, Peter G. Bergmann, that I developed a moral vision inspired by science. History has shown us that a separation between science and our morals is not only undesirable, but also dangerous. Science has progressed beyond narrow professional interests to embrace a broad range of universal issues, including ethical questions. Scientists have a responsibility to “show up.”

Such issues underscore science diplomacy [i.e., elevating the role of science in foreign policy to address national and global challenges]. What can professional organizations do to help?

With regard to a possible conflict between scientific exchange and human rights advocacy, these organizations should collaborate and not overlook abuses.

I have been critical of the New York Academy of Sciences for not speaking out against human rights abuses in countries with which they collaborate. In fact, they and other societies, including AAAS [American Association for the Advancement of Science] and ACS [American Chemical Society], are trying to improve access to basic human rights. This work is very good; however, it often fails to help oppressed researchers and physicians whose basic rights have been denied. There is a reluctance among some organizations to criticize countries such as China with poor human rights records.

What about the United States' record?

Not perfect. We have had some scientists of Chinese origin who were accused of spying and then put in jail for long periods. Fortunately, our courts were able to rectify such actions, but they could not reverse the harm done.

The Committee of Concerned Scientists is dedicated to protecting the human rights and scientific freedoms of our colleagues around the world—scientists, physicians, engineers, scholars. Some of our current cases involve scientists of dual nationality held in jail in Turkey, Iran and other countries.

Were you always interested in science?

Not necessarily in science, but in knowledge. I was born into a Jewish family in a small village in the Carpathian Mountains, then part of Czechoslovakia. Like almost every other Jewish boy, I went to a Jewish heder and then, as a teenager, went to a yeshiva for further Talmudic study. Even though my father ran a textile store, he studied rabbinical subjects. I also had a great grandfather and several uncles who were rabbis.

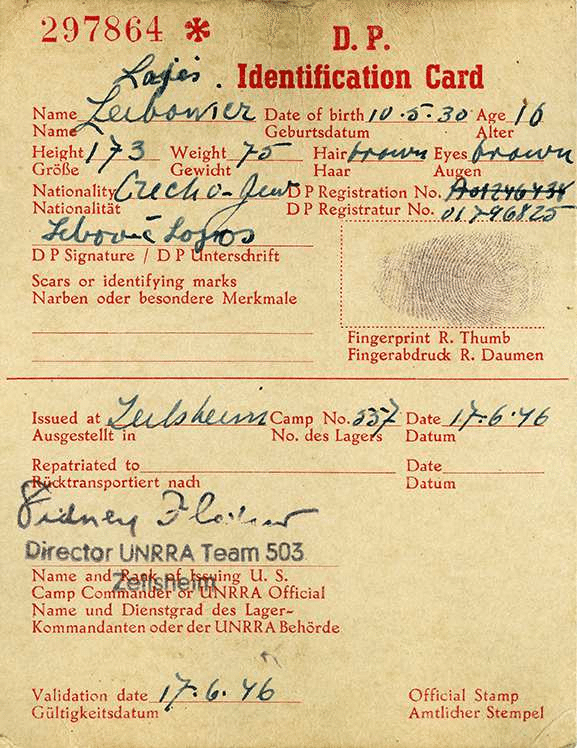

Everything changed in 1944, when I turned 14. The Hungarian authorities, acting on orders from the Germans, sent my family and me to Auschwitz. The trip there was horrible—a week in a crowded cattle car, with no food or water, no toilet facilities.

When we got there, the Gestapo was pushing women, children and old people into one line and healthy looking men into another. I followed my father into that line. I believe the nefarious Dr. [Josef] Mengele was there, inspecting everyone, sending those who looked weak to the other side. When I came up to him, he looked at me and asked how old I was. Some instinct told me to lie and say I was 15. I passed. If I had joined the other group, I most likely would have gone with my mother, sister, grandmother and aunts to the gas chamber.

By the time Germany was defeated in May of 1945, most of family members, including my father, were dead.

I can't imagine how these experiences affected you and your career.

I was lucky. I soon immigrated to the United States, through a program led by Eleanor Roosevelt for children orphaned by the war. I studied engineering and then theoretical physics at Brooklyn College, which had some very, very good people there—really excellent teachers, including Melba Phillips, a wonderful person and scientist, as well as a leading physics educator.

She taught a course in statistical mechanics, using a textbook by Peter Bergmann. His book got me interested in the subject from a physical and mathematical point of view, so I decided to study with him at Syracuse.

By then [the early Fifties], Peter Bergmann was still working mostly in general relativity, right?

He had been one of Einstein’s postdocs and collaborators, and was a leading figure in the field [of relativity]. Peter had many graduate students doing relativity—Joshua Goldberg [G’50, G’52], Jim Anderson [G’52] and Ralph Schiller [G’52]. I was good friends with Ted Newman [G’55, G’56], who, along with Roy Kerr, discovered the Kerr-Newman metric, describing space-time geometry within a charged, rotating black hole.

Peter would have been pleased with Syracuse’s role in the recent discoveries of gravitational waves. The work he and his students and collaborators carried out there was important for the development of general relativity.

What else do you remember about Syracuse?

I did my master’s thesis with Melvin Lax, then a young assistant professor who later chaired the theoretical physics department at Bell Labs. I also worked with Eugene P. Gross, who went on to develop an important equation in superfluidity.

Their research, combined with Peter Bergmann’s interest in non-equilibrium statistical physics, set the stage for my work in statistical mechanics.

Which is—

The connection between the movement and dynamics of microscopic particles and the macroscopic objects we observe.

We can apply statistical concepts to all kinds of phenomena—the weather, material properties, living systems, the stock market. Such knowledge can explain day-to-day things, such as why the tires on your car get hot after driving, or help us understand fundamental questions about the universe, such as how stars form galaxies and how galaxies become super galaxies.

As a scholar and an advocate, you're still in the vanguard.

I like math, and I like theoretical science. The search for knowledge fascinates me. I can’t think of living any other way.