The Brain That Changed Everything

A chance encounter with an honors lecturer at Syracuse set Alexander R. Weiss '12 on the path to scientific success

Alexander R. Weiss ’12 has a library full of books and journals, from arcane treatises on science and engineering to timeless works of literature and philosophy.

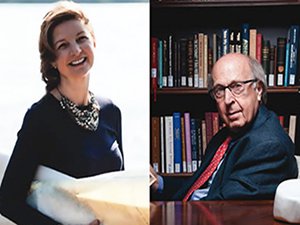

One book he holds dear is The New York Times Bestseller “The Brain That Changes Itself” (Viking Press, 2007), by Norman Doidge, a Canadian psychiatrist and award-winning science writer.

“At Syracuse, I was part of The Renée Crown University Honors Program [in the College of Arts and Sciences], which brought him to campus in 2009,” recalls Weiss, who earned a bachelor’s degree in bioengineering from the College of Engineering & Computer Science (ECS). “Dr. Doidge discussed how neuroplasticity is challenging the traditional, hard-wired model of the brain in favor of something more malleable.”

A polymath with a flair for neuroscience, Weiss recalls Doidge’s Honors Lecture with pinpoint precision. At one point, Doidge showed a video clip of a woman with damaged inner ears who suffered from a perpetual sense of falling. Seated in a neuroscience lab wearing a wired hard-hat, she had electrodes taped to her tongue. Technology enabled her to send signals to her brain via the tongue, thus bypassing pass the damaged vestibular system. “Within a year, she was healed because the electrical impulses had rewired the brain,” Weiss says.

Imagine his surprise when, the day after the lecture, Doidge visited his classroom. Weiss was in “Linked Lenses,” a popular honors course co-taught by professors Cathryn Newton and Samuel Gorovitz. “Dr. Doidge signed my copy of his book, and sent me down the path I’m on now,” says Weiss, speaking by phone from Baltimore, where he is a postdoctoral research fellow in neuroengineering at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). “I still have that book, and often refer to it.”

Weiss has come a long way, literally, from that galvanizing encounter. He has spent the past six years shuffling between Exeter College (one of the constituent colleges at the University of Oxford), earning a doctorate in biomedical science, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in Bethesda, Maryland, completing multiple fellowships.

Weiss no longer accrues frequent-flier miles the way he used to, but the accomplished young experimentalist is earning other kinds of points from his JHU colleagues.

For example, 60- to 80-hour workweeks in JHU’s Cognitive Neurophysiology and BMI Lab are de rigueur. “BMI” refers to “brain-machine interface,” a growing field that uses movement- and other behavior-related neural activity to control prosthetic limbs and communicate with computers.

“I perform clinical research on BMI, functional mapping of language processes and cognitive neuroscience,” Weiss explains. “It is exciting, rewarding work, and has the capacity to develop assistive systems for individuals with disabilities.”

The postdoc is in exalted company. His supervisor is the inimitable Nathan Crone, a pioneer in cognitive research, neuro-engineering and electrophysiology. “He does real-time mapping of brain function in patients to reduce the possibility of impacting their brain function during surgery for epilepsy,” Weiss says. “This reflects our larger mission of understanding the neural mechanisms of motor, sensory and language functions.”

Weiss arrived at JHU in September and expects to remain there for a few years. Meanwhile, he is in early talks with prospective employers from Harvard, Stanford and Caltech. “I can’t say much, other than the projects involve really cutting-edge stuff. Until then, I will stay here, doing clinical research or getting involved with its vibrant startup scene,” he says.

Growing up in the shadow of the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University, Weiss seemed destined for a career in Philly. His parents were dyed-in-the-wool Ivy Leaguers—his father a civil engineer, his mother a chemical engineer. Trips to Penn, Penn State and Temple were frequent. “Then I visited Syracuse and fell in love with the campus. Didn’t hurt that I liked cold weather,” Weiss says, half-jokingly.

Meeting Gustav Engbretson, professor emeritus of biomedical and chemical engineering at Syracuse, sweetened the deal. Weiss first encountered the affable professor during his junior year of high school. “Gus was the nicest guy,” Weiss remembers. “He was a bioengineer who was into retinal degenerative disease.”

Engbretson told Weiss something he never forgot—that choosing an undergraduate program is like deciding whom to date in middle school. “It should be fun and feel important at the time, but it leads to bigger and better things in the long run,” Weiss recalls him saying.

At Syracuse, Weiss blurred the boundaries of professional and liberal arts learning. When not working in the Syracuse Biomaterials Institute (SBI), he could be found poring over books on statistics (his minor), playing trumpet in the marching and pep bands or studying multidrug tolerant infections in implant patients—the focus of his Honors Capstone project.

Recognition seemed to follow him everywhere, often in the form of scholarships and memberships in academic honor societies.

Cathryn Newton, professor of Earth and of Interdisciplinary Sciences, was an ardent early champion of his. “Alex’s creativity and incredible abilities of associative thinking are his hallmarks. He is quiet, funny, committed, insightful—in short, everything one would seek in a scientific colleague,” says the A&S Dean Emerita, who also is Senior Advisor to the Chancellor and Provost for Faculty Engagement.

Another proponent was Weiss’ senior thesis advisor, Jeremy Gilbert, then professor of biomaterials in ECS. Both logged hundreds of hours in SBI, studying how bacterial biofilms attached to metal surfaces and interacted with different electrochemical processes.

Weiss had an innate grasp of what they were doing—rare for an undergraduate, explains Gilbert, the newly appointed Hansjörg Wyss Endowed Chair for Regenerative Medicine at Clemson University. “Alex learned the methods that were required, including how to use an atomic force microscope to image and measure bacterial changes associated with the interactions. He was a pleasure to have in my lab.”

A highlight of their partnership was the Society for Biomaterials Annual Meeting and Exposition in Orlando, where Weiss presented his and Gilbert’s findings before a blue-ribbon audience of academic, healthcare, governmental and business professionals.

Was the Syracuse junior nervous? A little, but he did not show it. “Alex acquitted himself quite well. He was poised, focused and clear in his communication,” Gilbert adds.

Fate intervened during Weiss’ senior year, when he found out about the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Oxford-Cambridge Scholars Program. If selected, Weiss could spend two years in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Medicine, followed by three years at the NIH campus in Bethesda—the largest biomedical research facility in the world.

“I told Professors Newton and Gorovitz about it, and they said I should ‘100-percent apply.’ The fellowship seemed like a pipe-dream,” he recalls.

Newton and Gorovitz worked closely with Weiss—meeting with him frequently, encouraging him to keep refining his application materials, urging him to be openly clear about his love of literature and of liberal education. They also arranged a mock panel interview, rounded out by Biology Professor John Russell, Gilbert and several ECS staffers. “It worked out, I guess,” Weiss says in a classic piece of understatement. “Shortly after graduation, I was on a plane to London.”

Weiss muses wistfully about life after Syracuse. At Oxford, he trained under Tipu Aziz, the Bangladeshi-born, British neurosurgeon, known for his innovative treatments for Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis and neuropathic pain. Aziz also founded the U.K.’s first functional neurosurgical unit dedicated to novel approaches to the surgical treatment of brain disorders.

“It was amazing to see his surgeries offer hope to patients battling Parkinson’s and to people wanting to walk again,” says Weiss, who worked with the renowned professor from 2012-14.

As the calendar flipped to 2015, Weiss returned stateside, spending the next three years with Judith Walters at NINDS. Walters is famous for many things, notably her studies of mechanisms in the brain that mediate dysfunctions associated with neurological diseases and disorders.

She says Weiss’s academic grooming, particularly in BMI and deep brain stimulation (in which implanted electrodes help the brain control body movements), was a boon to her research into Parkinson’s disease.

“Alex has a combination of skill sets that make him popular on the job circuit,” notes Walters, senior investigator and chief of NINDS’ Neurophysiological Pharmacology Section. “He is experienced with engineering-related tasks, rodent and human neurophysiology, behavioral studies, rodent neurosurgery and complex techniques for data analysis. These qualities enable him to investigate changes in brain function in a range of neurological disorders.”

Weiss’ soft skills are equally commendable. Walters says his “good-natured collegiality” made him popular among trainees and summer students. “He was one of my lab’s best mentors. He was kind and understanding, but also politically astute,” she says, noting his gift for a well-placed joke or piece of advice. “I look forward to hearing great things about him in the future.”

Weiss capped off his NINDS experience with a five-month postdoctoral fellowship, following graduation from Exeter in April.

Admittedly, having a “piece of paper” from one of the oldest, most respected colleges in the world (Exeter is more than 700 years old) is “pretty terrific,” Weiss says, but he would not have gotten it without his Syracuse education.

“What I accomplished at SU—combining my knowledge of engineering and statistics with a burgeoning interest in neuroscience—laid the groundwork for what I do today at Johns Hopkins,” says Weiss, who resides in the Capital Beltway community of Silver Spring. “Just as importantly, Syracuse instilled in me an entrepreneurial spirit—the desire to find creative solutions to tough problems.”

Weiss considers intellectual entrepreneurship more than an occupation; it is an attitude, a way of life for him. He credits his Syracuse professors, especially those in A&S and ECS, for teaching him the value of hard work; grit; and wide-ranging, associative, creative thinking.

“Sometimes, the best ideas are the craziest ones, but you have to start somewhere—to be willing to make mistakes or fail,” says Weiss, citing the concept of risk and reward. “I am reminded of this almost daily in Baltimore, which, with its proximity to Washington, D.C., and with Johns Hopkins’ commercial arm [JHU Technology Ventures], is filled with smart people with incredible ideas.”

Perhaps what Weiss is doing at JHU—and has undertaken thus far at Syracuse and Oxford—affirms the Norman Doidge adage that “we see with our brains, not our eyes.”

In a final nod to that psychological mentor, Weiss says, “The same intelligence that allows us to worry and anticipate negative outcomes allows us to plan, hope and dream.”

Without missing a beat, he adds, “It’s important to keep our head in the game.”

Media Contact

Rob Enslin