Society for New Music Premieres ‘Pushed Aside: Reclaiming Gage’ Jan. 21 at OnCenter

Students, faculty, alumni shine in new opera about suffrage pioneer Matilda Joslyn Gage

In 1868, a young domestic worker in Philadelphia named Hester Vaughn made headlines for allegedly murdering her newborn infant. Never mind that Vaughn’s employer raped and then fired her after finding out she was carrying his child. Vaughn had no choice but to give birth alone in an unheated rented room, where police found the teenager critically ill with her dead child beside her. Worried about the growing rate of infanticide, the judge decided to make an example of Vaughn, and sentenced her to the gallows.

Among the people who took up Vaughn’s cause were women’s rights leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who argued that the accused had not received a fair trial. (The all-male jury likely was a giveaway.) Stanton, in fact, supported the Working Women’s Association (WWA), which sent Clemence Lozier—one of the nation’s first women doctors and a graduate of the now-defunct Syracuse Medical College—to investigate Vaughn. Afterward, Lozier called a mass meeting, demanding, among other things, Vaughn’s acquittal and an end to capital punishment. The governor eventually pardoned Vaughn, who, by then, was a symbol of the burgeoning women’s rights movement—and an indictment of sustained patriarchy.

“Long before Harvey Weinstein or the #MeToo movement, there was Hester Vaughn, whose case reflected the institutionalization of rape in the United States,” says Sally Roesch Wagner, founder/director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation in Fayetteville, New York, and an adjunct professor in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). “The WWA, along with Anthony and Stanton, showed that, when women organized their efforts, they could do things that were virtually impossible on their own.”

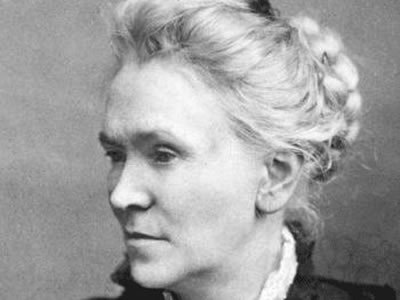

Some argue that Anthony and Stanton would have gotten nowhere without the efforts of the aforementioned Gage. A native of Cicero, New York, Gage was a seasoned journalist, editor and feminist historian, who specialized in the plight of women since the advent of Christianity. Her complicated relationship with Anthony and Stanton—from the trio’s fateful meeting in 1852 to their public falling out in 1890—is the basis of a new opera titled “Pushed Aside: Reclaiming Gage,” by Ithaca-based composer Persis Parshall Vehar.

Commissioned by the Society for New Music (SNM), “Pushed Aside” premieres on Sunday, Jan. 21, at 4 p.m. in The OnCenter’s Carrier Theater (800 S. State St., Syracuse). Tickets are $15 for adults and $12 for students and seniors, and are available by visiting societyfornewmusic.org/concerts.cfm or calling 315.251.1151.

For more information, including a study guide about the opera, log onto societyfornewmusic.org.

SNM Program Advisor Neva Pilgrim produced the two-act opera, made possible by New York State’s Regional Economic Development Council initiative and the Central New York Community Foundation.

The premiere is part of a spate of events that marks the centennial of women's suffrage in New York State in 2017 and continues until 2020, with the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendement.

“Gage, Anthony and Stanton formed a triumvirate of early women’s suffragists,” says Wagner, a nationally recognized lecturer, author and performance interpreter of women’s rights history who teaches in the Renée Crown University Honors Program. “The title is fitting because Gage fought for others who had been ‘pushed aside,’ notably African Americans and Native Americans. In the end, she was ‘pushed aside' by members of her own movement—and right out of the history books. The time is ripe for her reappraisal.”

Vehar echoes these sentiments, explaining that the current culture of fighting back against sexual assault has been hundreds of years in the making. “Years ago, when I was teaching at the Crane School of Music [at SUNY Potsdam], one of my female students said that the demise of opera was due, in part, to women being portrayed as either ‘angels’ or ‘whores,’ but always as ‘victims,’” she says. “This student couldn’t identify with the portrayal of women in opera, and nor could I. I’m sure Matilda Joslyn Gage didn’t, as well.”

“Pushed Aside” marks Vehar’s eighth fully staged opera and second partnership with SNM, which has been commissioning, presenting and performing new music throughout Central New York since 1971.

SNM also commissioned Vehar to write the 2011 opera “Eleanor Roosevelt,” produced by Pilgrim and based on a book and play by the late A&S visiting professor Rhoda Lerman.

“Pushed Aside” is the fourth collaboration between Vehar and her daughter Gabrielle, an accomplished librettist. While Vehar is proud of the familial connection, she treats Gabrielle more like a colleague than a daughter—at least in this context. “I look for someone who knows how to write; has a professional knowledge of drama and dance; and is familiar with music, especially opera,” says Vehar, who has more than 300 works to her name. “Gabrielle’s qualifications fit these criteria, and that’s why I enjoy working with her.”

The mother-daughter team is not the only highlight of this mostly all-female production. Almost everyone onstage—and in the original story—has ties to Central New York, including mezzo-soprano Danan Tsan (Gage) and soprano Juliane Price (Anthony). Soprano Laura Enslin (Stanton) teaches voice in the Musical Theater Program in the College of Visual and Performing Arts (VPA)’s Department of Drama and in jazz and commercial music in VPA’s Setnor School of Music.

Other VPA affiliations are singers Julia Ebner ’04 (Maud Gage Baum), Jonathan Howell ’18 (Isaac Thomas) and Greggory Sheppard ’00 (Frederick Douglass) and pianist Sar-Shalom Strong G'98.

Pilgrim notes that Gage helped shape the utopian feminist vision of L. Frank Baum, author of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz," who was married to her daughter Maud.

“This opera is mostly by and about women,” she says, pointing out that the production’s conductor and director—Heather Buchman and Victoria King, respectively—also are women. “The focus, however, is on Matilda Joslyn Gage, who believed that all freedom struggles are equal and interconnected.”

A frequent conductor and trombonist for SNM, Buchman says the score is driven by the text and ideas expressed by the main characters. “The opera reminds me of Poulenc’s ‘Dialogues of the Carmelites,’ in that it focuses on women thinking about and grappling with deep philosophical and moral issues and principles in the face of what’s going on around them,” says Buchman, professor and chair of music at Hamilton College. “The accent of American English and its rhythmic character gives the music its particular character. The ideas expressed are, thus, crucial to get out in the performance.”

“Pushed Aside” opens in 1901 in Fayetteville Cemetery in New York, where Frank and Maud Baum are visiting Gage’s gravesite, recalling her disapproval of their engagement decades earlier.

The action switches to Gage’s home in Fayetteville, where 26-year-old Matilda has returned from delivering her first speech at the National Women’s Rights Convention in Downtown Syracuse. Also making her speaking debut has been Anthony, a Rochester native who had joined the women’s movement with Gage in 1852.

With Anthony and Stanton (who helped organized the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848), Gage forms the third of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) triumvirate. Together, they produce a remarkable body of literature, including a “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States” (1876) and the first three of the six-volume “History of Woman Suffrage” (1881-1922). Among the trio’s demands are ownership of their own wages and the right to act as free agents, without relying on husbands, fathers or male relatives to speak for them.

“Initially, all three got along with one another, and were at the forefront of the early struggle for women’s rights,” Wagner explains. “Over time, their roles began to change and become more defined. Gage and Stanton were the theorists. Anthony was the activist.”

Toward the end of Act I, Gage turns her attention to the Civil War. She becomes an enthusiastic supporter of runaway slaves and Union soldiers, encouraging them to let liberty be their “watch-word and war-cry alike.” Gage also helps persuade President Lincoln to publicly admit the war is about ending slavery, not preserving the Union.

“When the women’s movement emerged in the 1830s and ’40s, it was a radical movement, which criticized both church and state,” says Carol Faulkner, an associate dean and a professor of history in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. “After the Civil War, as activists became more focused on the question of suffrage, they created coalitions within a broad array of women, temperance activists and white Southerners, who were more conservative on matters of religion and race. As a result, the suffrage movement lost some of its radicalism and some of its radicals, including Gage.”

These differences become more pronounced in Act II, which follows the second half of the trio’s relationship—a prolific, yet turbulent period, spanning from the 1870s to the 1890s. A top officer in the NWSA, Gage fights assiduously for women’s and civil rights. She also enmeshes herself in treaty rights and tribal sovereignty, leading to an honorary adoption into the Wolf Clan of the Haudenosaunee’s Mohawk Nation.

“Like Gage, African American and Native American women were concerned with issues of racial violence, survival, war, disenfranchisement and dislocation,” Faulkner says. “Although these groups have been written out of suffrage history, it does not mean that they weren’t there. … With Native Americans, Gage had a more universalist vision of rights that grew, in part, out of a sense of place—her home in Central New York—and her related interest in the matrilineality of Native Americans.”

Discouraged by the slow pace of suffrage efforts and the fast-growing conservative religious movement (whose ultimate goal is to form a Christian state), Gage creates the Women’s National Liberal Union in 1890. Her goal? To stop the unification of church and state. She reiterates her views in the aptly titled “Woman, Church and State” (1893), which all but severs ties with her NWSA sisters.

“Anthony wanted to align with Christian women’s groups, but Gage and Stanton [who co-wrote the Women’s Bible in 1895-98] did not,” says Tsan, a frequent soloist with Symphoria and Syracuse Opera, who teaches voice at Le Moyne College. “Gage felt Christianity had oppressed women and reinforced patriarchal systems. She was deliberately written out of the history books after her death in 1898, as the suffrage movement became increasingly conservative.”

Vehar says Gage never lost sight of the “larger picture”—something that, in the short term, led to her undoing, but ultimately transformed Central New York into a hub of free thought and radical activism. “She knew that, to paraphrase Aristotle, inequality brings instability,” Vehar says. “Matilda Joslyn Gage practiced and taught respect for men and women of all races, nationalities and religions. No one should be pushed aside.”

The opera ends as it begins—in Fayetteville Cemetery, with Frank and Maud Baum reflecting on the many ways in which Gage inspired them and millions others.

Buchman, for one, is “blown away” by the timeliness and relevance of the subject matter. “The parallels between the three women speaking out about no longer being silenced and today’s #MeToo era—the Silence Breakers—are uncanny,” she says. “This fight for true equality, this national conversation, is every bit as much with us today as it was then.”

Tsan agrees: “Women still have to fight to not be grabbed by the [expletive] by the president of the United States.”