'The Real Thing'

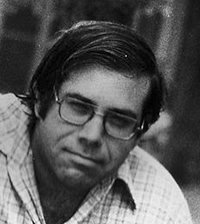

Composer John Liberatore '07 draws on his CNY roots to achieve national success

Franz Joseph Haydn probably would be glad to know that his legacy lives on in the small mountain town of Bradford, Pa. There, on the satellite campus of the University of Pittsburgh, visiting professor John Liberatore ’07 was inspired to do what Papa Haydn accomplished some two centuries earlier: adapt Scottish poetry to music.

Never mind that Liberatore’s source material, the classic “She rose, and let me in,” had already enjoyed life as a folksong, before poet Robert Burns took a pen to it in the 1790s. Or that some of Haydn’s contemporaries, including Beethoven and Ignaz Pleyel, had done their own renditions of the poem.

Yet, it is Haydn’s lyrical setting for voice and piano trio—one of more than 200 Scottish airs he arranged near the end of his life—for which “She rose” is probably best known, and serves as the impetus behind Liberatore’s solo piano work by the same name. Talk about standing on the shoulders of giants.

“What drew me to this piece was a recording I had gotten for my birthday,” says Liberatore, speaking by phone from his home in southwestern New York, near the Pennsylvania border. “The recording was part of a 150-CD set of the complete works of Haydn, which included arrangements of all these Scottish folksongs I had never heard before. Most of the songs aren’t that well known anymore, but Haydn’s arrangements are remarkable.”

Liberatore says he was transfixed by Haydn’s treatment of “She rose,” describing the texture as “elegant and beautiful” and the interplay of pitches as “graceful.” But it was the tune, itself, that got lodged in Liberatore’s head, and needed to be “worked out” in his own inimitable way. The result? A sparkling set of Haydnesque variations, capped off by a fugue of sublime complexity.

“I guess that’s the root of everything I do,” says Liberatore, who, on the strength of “She rose,” won the 2014 Brian M. Israel Prize, co-sponsored by the Society for New Music (SNM) and the New York Federation of Music Clubs. “Music stays with me,” he says. “It rattles around, and I'm always looking at it from different sides, imagining news ways to hear it. It’s a never-ending process, and is one of the most exciting—and frustrating—things about being a composer.”

Bradford is only a three-hour drive from Liberatore’s hometown of Auburn, N.Y., but it is light years from where he got his start as a musician. At Syracuse University, Liberatore majored in composition in the acclaimed Setnor School of Music, where he also excelled at theory and piano. Working with such blue-chip professors as Daniel Godfrey, Nicolas Scherzinger, and Andrew Waggoner enabled Liberatore to not only find his voice, but also garner some of the College of Visual and Performing Arts (VPA)’s highest honors, including being named a VPA Scholar.

Waggoner recalls Liberatore as having a strong personal sense of mission. “John was unique the moment he stepped onto campus,” says Waggoner, professor of music composition, theory, and history. “The first pieces he wrote for me were outsized, anachronistic, wildly romantic, and full of mordant, post-adolescent humor. They were also clearly intentioned, deeply musical, and hugely personal. They revealed a voice, one that has only deepened and become more authentic with time. He’s the real thing.”

In those days, no one figured more prominently in Liberatore’s off-campus development than SNM co-founder Neva Pilgrim. She immediately recognized his gifts as a keyboardist and composer, and set about featuring him at some of SNM’s marquee events, including the Cazenovia Counterpoint festival and Rising Stars concert series.

The combination of world-class instruction at the University and on-the-job training with SNM proved ideal. By the time Liberatore graduated summa cum laude, he had several commissions under his belt and a summer residency at the Bowdoin International Music Festival in Brunswick, Maine.

“Anybody who lives in Syracuse and is interested in new music knows Neva,” says Liberatore, who begins work this fall as an assistant professor of music theory and composition at the University of Notre Dame. “She remains a huge support to me, and has been central to my career.”

Pilgrim returns the compliment, pointing out that Liberatore epitomizes the kind of composers and performers SNM seeks to support. “Some people think great artists step from their practice room right onto the stage of Carnegie Hall, but, in reality, there’s a lot of nurturing that goes on behind the scenes,” she says. “The Israel Prize, which comes with prize money [$750] and multiple performances over a couple of years, is designed to support emerging composers in the region, such as John, who are under the age of 30 and show real promise.”

Liberatore is not lost on the significance of the Israel Prize, which is named for the gifted University composer who died from leukemia in 1986 at age 35. Like Israel, Liberatore explores shifts in mood and emotion, often following a witty movement by a serious one.

That the Israel competition accepts submissions from all over New York State and is judged anonymously makes Liberatore’s achievement even more remarkable. “Brian Israel was an extremely gifted composer, so it seemed appropriate to name a prize after him, following his untimely death,” Pilgrim says. “John is a ‘wunderkind’ in the way Brian was, and his receipt of the Israel Prize is a wonderful way to honor Brian’s memory.”

Already, “She rose” has been performed by several pianists, including Eunmi Ko, who gave the piece its New York premiere last summer at Carnegie Hall. Plans are underway for her to commercially record it this fall.

Ko, who has worked with Liberatore for several years, marvels at how he masterfully weaves together ideas, while playing to the strengths of each instrument. “‘She rose’ plays beautifully on the piano,” says Ko, whose new music ensemble, Strings & Hammers, has championed other pieces of his. “Then again, it doesn’t compromise its musical quality for the sake of the instrument. As a pianist, I feel lucky to have a piece like this [in my repertoire].”

No doubt that Ko is echoing the sentiments of other industry tastemakers. In addition to the Israel Prize, “She rose” won the prestigious ASCAP Foundation Morton Gould Young Composer Award—Liberatore’s second such award from that organization—and made him a finalist for the Julius F. Ježek Prize, sponsored by The Harry and Alice Eiler Foundation.

Adds soprano Jamie Jordan, who has performed Liberatore’s music in New York and Philadelphia: “John is thoughtful and clever in choosing and setting text. A respectful collaborator, he has tremendous creative vision … and a keen sense of orchestration.”

Expectations are high, as Liberatore embarks on the next chapter of his career. In addition to an upcoming premiere in Manhattan by the New York Virtuoso Singers, Liberatore looks forward to his new role at Notre Dame. “It will be a cultural shift, going from a small liberal arts college in the mountains to a big university in the Midwest, but I’m excited,” says Liberatore, who also has taught theory at Syracuse. “In some ways, it will be a culture I’m used to.”

Undoubtedly, Liberatore is referring to his time at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., where he earned master’s and Ph.D. degrees in composition, studying under such luminaries as Robert Morris, David Liptak, and Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon.

If Syracuse helped launch Liberatore’s career, then Eastman solidified it. During his seven years there, Liberatore worked relentlessly, writing for various acoustic and electronic ensembles, landing residencies in such far-flung locales as Switzerland and Japan, and presiding over the school’s forward-looking Ossia ensemble. “I went to Eastman mainly because of David Liptak’s music, but, while I was there, I ended up studying with Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon, who was an excellent composition teacher, and Bob Morris, who had a huge impact on my scholarly work,” he says.

Liberatore’s graduation from Eastman last fall coincided with the premiere of his one-act chamber opera, The Investment, by the Washington National Opera. Based on an original libretto by Niloufar Talebi, the 20-minute work is about an Iranian couple who buys a painting by an Iranian artist, only to learn that they don’t agree with his political sentiments. Critically, The Investment was a success, with Anne Midgette of The Washington Post stating that she “quite enjoyed” the work. “Liberatore opened and closed his piece in a kind of mirror-image parentheses: a rumble of timpani and bass leading to a sparkle of xylophone followed by a solo cello at the beginning, the same instruments tying up the package in reverse at the end,” she wrote. Another reviewer praised Liberatore for “putting life into the libretto’s social argument.”

For all his success as a composer, Liberatore is careful not to take himself too seriously. For instance, his artist statement page is “always, always, always under construction.” Liberatore also tries not to come off as too high-minded or unintentionally sincere. “I have a lot of different interests, which I bring together to create contradictory aesthetic results,” says Liberatore, who has drawn inspiration from Old English nursery rhymes, surrealistic cartoons, and even a 16th-century zoological treatise. “Really, I write music to be understood, and that’s different from writing music that people understand.”

Media Contact

Ron Enslin