SU professor, dean emerita lauded for role in discovery of Civil War ironclad

Cathryn R. Newton was a 16-year-old college student when she helped her father discover the U.S.S. Monitor

Cathryn R. Newton, Syracuse University’s only Professor of Interdisciplinary Sciences and dean emerita of The College of Arts and Sciences, was honored by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the state of North Carolina Maritime Museums at a ceremony in Beaufort, N.C., marking the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the U.S.S. Monitor, the most famous Civil War ship and, indeed, the most important single ship in all U.S. naval history.

Newton presented an address at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, where the inaugural marker of the U.S.S. Monitor Trail was dedicated. This U.S. marker contains a historical account and images of Newton and others involved in the 1973 discovery. In coming years, stops on the trail will be created at sites important to Monitor’s history along a 600-mile route from Beaufort to New York.

In Beaufort, Newton was joined by a host of luminaries, including David Alberg, sanctuary superintendent of the NOAA; Joseph Schwarzer, head of the North Carolina Maritime Museums; Richard L. Stanley, mayor of the Town of Beaufort; Bobby Springle and Paul Kelly, other members of the Monitor discovery team; and George and Janice Weinmann, descendents of Grenville Weeks, one of the ship’s survivors.

“Forty years ago—at this very moment—we were at sea and hard at work on a new target: a shipwreck,” Newton told the rapt audience on Aug. 27. “It was Day 11 of a 14-day research trip, and time was running out.”

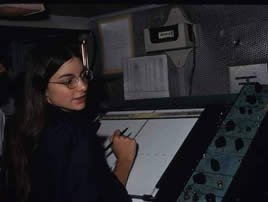

Newton recalled how in August of 1973, as a 16-year-old sophomore at Duke University, she helped her father—John G. Newton, then superintendent of Duke’s marine laboratory and leader of the Monitor discovery team—locate the warship in approximately 230 feet of water, off the coast of Cape Hatteras, N.C.

She explained that Monitor sank in a dangerous storm in the early hours of December 31, 1862. Remarkably, only 16 of the 62-member crew perished. One of the survivors was Weeks, a 56-year-old surgeon who later published a firsthand account of the experience in The Atlantic Monthly. “He provided us with the very last sighting of men on the Monitor’s turret,” said Newton.

Monitor is best known for clashing with the Virginia at Hampton Roads, Va., in March 1862. The Civil War battle, which came to a draw, was the first between two ironclad warships. Monitor and Virginia were built by the Union and Confederacy, respectively.

Back at SU, Newton explains how the 1973 expedition took on added significance with the finding of another shipwreck. “We spent three days studying something that turned out not to be Monitor,” she says. “What we discovered was the American YP-389, a humble trawler sunk by a German submarine in 1942. It was then, following this so-called ‘failure,’ we found the target that was Monitor—something that showed up initially as little more than a small smudge on recorder paper.”

Newton credits Monitor's discovery, in part, to Edgerton’s side-scan sonar, a type of underwater imaging used in conjunction with a microwave-based navigation system. She says that Edgerton, along with thousands of other administrators and researchers, helped give the story international legs. That Monitor was designed by John Ericsson, a Swedish-American inventor and mechanical engineer, has fueled the story’s cosmopolitan appeal.

“It’s inherently international,” says Newton, who participated on March 8 at Arlington National Cemetery in the interment, with full military honors, of two crewmen, found more than a decade ago in the Monitor’s turret. Newton’s role as one of the discoverers and as a contributor to oceanography ever since was acknowledged that day at a gathering of Monitor descendents, Navy officials, members of the press, and many others. Newton adds: “The Monitor, Ericsson, and 40th anniversary of the discovery were publicly remembered this past summer with two major events in Sweden: one near Ericsson’s birthplace and another in Stockholm.” Newton was honored near the birthplace, and, along with U.S. Ambassador to Sweden Mark Brzezinski, was honored again at the Stockholm event.

Obviously, Newton has the sea in her veins. Like her late father, she has built a stellar career as an oceanographer, in addition to her distinction as a paleontologist. In 2009, she unveiled a searchable database of some 2,000 ships that have sunk off the North Carolina coast since the 1500s. Much of the database has drawn on more than 5,000 handwritten data cards, compiled by her father, Edgerton, and other members of the Monitor discovery team.

"Shipwrecks can be imagined as large fossils that sink to the sea floor, much as deceased whales sink and become part of the fossil record," says Newton, who has nearly completed a book about shipwrecks. "Like other marine fossils, shipwrecks provide clues to the part of our history that lies beyond the shoreline."

Since joining the SU faculty in 1983, Newton has served as an award-winning teacher, scholar, and administrator, as well as a mentor to women in the sciences, as evidenced by her co-founding the Women in Science and Engineering Program. As dean of The College (2000-2008), she implemented many important curricular and capital initiatives, including the construction of the Life Sciences Complex and renovation of the Tolley Humanities Building. She is the University’s inaugural Professor of Interdisciplinary Sciences, a testament to the broad scope of her scientific work.

Media Contact

Rob Enslin