SU launches Certificate in Iroquois Linguistics program

Undergraduate program targets students and teachers of Iroquois languages

In response to the growing demand for qualified language teachers, the Native American Studies Program in Syracuse University’s College of Arts and Sciences has launched the Certificate in Iroquois Linguistics for Language Learners. This new undergraduate program targets students and teachers of Iroquois languages, and is designed to bolster Iroquois language revitalization efforts.

Philip P. Arnold, associate professor of religion and interim director of the Native American Studies Program, says the need for Iroquois language teachers is critical. “There are 18 Iroquois language-speaking communities throughout northeastern North America, each of which boasts multiple language revitalization programs,” he says. “Traditionally, the language teacher was drawn from one of the elder native speakers of each community. But as elder speakers have passed away and younger people are primarily speaking English, the survival of these languages has become more and more critical.”

Arnold says the problem is exacerbated by Iroquois grammar, which is notoriously complex: “Since most of the teachers in these revitalization programs are second-language speakers, there’s a demand for linguistics courses in which learners and teachers can learn the concepts and terminology to make better use of dictionaries and descriptive grammars written by linguists.”

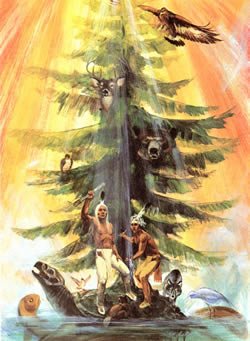

SU’s program focuses on the six languages of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. In addition to studying the grammatical systems of all six languages, students explore parts of the systems specific to each language. Special attention is paid to Iroquois verb structure, which instructor Percy Abrams says is one of the biggest hurdles for second-language speakers.

“Second-language speakers may acquire some idea about Iroquois grammar, based on what they know about English grammar, but in the case of Iroquois languages, most of what they know does not apply,” says Abrams, a member of the Eel Clan of the Onondaga Nation and holder of a Ph.D. in linguistics from SUNY Buffalo. “While native speakers acquire these grammatical systems naturally, second-language speakers generally have to learn a new grammar. Differences in grammatical structure cannot be easily overcome by analogies between English and Iroquois.”

Such information is traditionally of interest to not only students and teachers of Iroquois languages, but also linguists, anthropologists, and historians. The program takes three semesters to complete, and includes courses in Iroquois phonetics, phonology, semantics, verb morphology, and syntax. It culminates with a summer capstone course to demonstrate mastery of the grammatical systems in practice.

Abrams is acutely aware of the timing of this program. As the demand for language revitalization increases, so does the need for multiple instructors within each Iroquois community. “Iroquois languages are described as polysynthetic, fusional, and incorporating,” he adds. “’Polysynthetic’ refers to words made up of many parts. ‘Fusional’ denotes phonological changes that occur at the joining of these parts. And ‘incorporating’ is the process by which words or word roots are inserted into an existing word to add meaning to it. All of these factors make for a language family that is difficult to master but important to understand.”

Adds Arnold: “It’s important that educational institutions--which, historically, have been complicit in the demise of Iroquois languages—work collaboratively with Native communities to revitalize their languages and dialects. We at SU take this responsibility very seriously."

Media Contact

Rob Enslin