Paris Noir's 'jazz moment'

Popular study-abroad program enters second decade

In “Shadow and Act,” a collection of essays about the Black experience, Ralph Ellison describes jazz as the “art of assertion within and against the group.” Each jazz moment, he writes, springs from a context in which each musician challenges the rest of the group—every solo representing a link in the chain of tradition.

Although Ellison’s characterization is nearly 50 years old, it still resonates among scholars of the African Diaspora. Among those captivated by it is Janis Mayes, a Syracuse University professor who uses the “jazz moment” to conceptualize her popular summer program, “Paris Noir.” Each summer for the past decade, she has led 12-15 students on an intense journey through Black literature, art, and contemporary life in Paris and the surrounding “banlieue.” The result is a signature course that has not only put SU on the Diaspora map, but also addressed the question “What does Paris Noir mean today?”

Speaking by phone from her home in East Syracuse, New York, Mayes elaborates on the “jazz moment” metaphor. “Ralph Ellison thought that the balance struck among players in a jam session was a ‘marvel of social organization,’” she says. “This kind of framework applies to ‘Paris Noir’ because it supports an exchange of different perspectives. If the seminar was a piece of music, ‘Paris Noir’ would be the ‘theme,’ and the responses to my question [‘What does the “noir” in Paris Noir mean today’] would be a set of variations.”

One way to understand the “jazz moment”—and Mayes’ project , in general—is to look at its historical context. During the 1920s and ‘30s, the Harlem neighborhood of New York City was home to a growing number of African Americans (many of whom were from the South), whose experiences with racism were conveyed through art, literature, and music. This flowering of Black consciousness also occurred in France, which attracted many students, artists, and intellectuals (not to mention, returning World War I soldiers) from around the globe. The French emblem of equality, fraternity, and liberty must have seemed like a hit of fresh air to people under the yoke of colonization or segregation. Just some of the many ex-patriots were the cultural icon Josephine Baker; writers Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Anna Julia Cooper, Richard Wright, and Barbara Chase-Riboud; artists Henry O. Tanner and Beauford Delaney; and musicians Louis Armstrong, Ada “Bricktop” Smith, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, and Nina Simone.

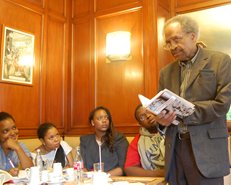

It is against this milieu that Mayes leads one of SU’s most innovative courses. During the five-week program, students stay at an “apartment hotel,” meet daily at the historic Café de Flore (a favorite of Baldwin’s and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s), visit historical and cultural landmarks, and discuss topics ranging from history and culture to race and identity. “Many conversations revolve around the idea of discernment—seeing what others regard as invisible in Black culture,” she says. “The students rigorously explore the ‘noir’ in French society, as it is expressed in the arts and in everyday life.”

The only program of its kind in the academy, “Paris Noir” is divided into three parts. The first, “On Becoming Paris Noir,” examines the historical, social, and political forces that led to a Black presence in Paris. “To focus on this aspect, we visit various museums and historical landmarks,” says Mayes. “At the Louvre, we study the large glass pyramid by I.M. Pei outside the museum’s entrance and the Egyptian art inside, drawing connections between Africa and the modern French world. We also analyze Picasso’s masks, which capture a borrowed aesthetic from ancient African sculpture, and Géricault’s highly influential ‘Raft of the Medusa.’”

The second part of the course examines the Paris Noir of today. Here, students pour over literary and cultural texts, as well as engage with such Black luminaries as saxophonist Archie Shepp, writer Jake Lamar, poet/activist Sonia Sanchez, historian Pap Ndiaye, photographer Kim Powell, publisher Christiane Yandé Diop, and members of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. (A few lucky students were able to meet singer Nina Simone and witness her last concert in France, months before her death in 2003.)

The third part of “Paris Noir” is an independent research project of the student’s choice. Mayes says this part can often lead to a personal awakening that is gratifying for student and teacher alike. “I want students to have a clearer sense of the beauty and struggle of living somewhere else and then use it to better understand themselves. I want ‘Paris Noir’ to touch them on a personal level,” she says. “Research can provide that catalyst.”

Kishauna Soljour and Tiarra Currie are undergraduates who attended “Paris Noir” last summer. “’Paris Noir’ changed my life as a scholar and a person through a process I call ‘re-learning,’” says Soljour, a junior majoring in African American studies and in television, radio, and film. “In the United States, I had been socialized to accept prepared truth and to regurgitate it, as if it were derived from my own psyche. In Paris, I ‘re-learned’ to question, communicate, and arrive at my own conclusions about my Black identity. As a result, I no longer question who I am. I have become the master of my destiny by accepting my identity with clarity and purpose.”

Currie--a senior majoring in psychology, with a triple minor in child and family studies, early childhood, and sociology—had a similar epiphany. She shares several experiences that reinforced her decision to study abroad, including one involving a panel discussion of Black women that was so moving, it “almost brought tears to [her] eyes.” “’Paris Noir’ exposed me to history like never before,” she says. “I felt like I had learned more about myself in those five weeks than in the past 20 years.”

Currie credits “Paris Noir” for helping her embrace her own Blackness. “I learned that there is no one Black face or Black story,” she continues. “All of us come from different backgrounds and have different complexions and experiences. It this common thread of racism and history that binds us together.”

Although Ellison’s characterization is nearly 50 years old, it still resonates among scholars of the African Diaspora. Among those captivated by it is Janis Mayes, a Syracuse University professor who uses the “jazz moment” to conceptualize her popular summer program, “Paris Noir.” Each summer for the past decade, she has led 12-15 students on an intense journey through Black literature, art, and contemporary life in Paris and the surrounding “banlieue.” The result is a signature course that has not only put SU on the Diaspora map, but also addressed the question “What does Paris Noir mean today?”

Speaking by phone from her home in East Syracuse, New York, Mayes elaborates on the “jazz moment” metaphor. “Ralph Ellison thought that the balance struck among players in a jam session was a ‘marvel of social organization,’” she says. “This kind of framework applies to ‘Paris Noir’ because it supports an exchange of different perspectives. If the seminar was a piece of music, ‘Paris Noir’ would be the ‘theme,’ and the responses to my question [‘What does the “noir” in Paris Noir mean today’] would be a set of variations.”

One way to understand the “jazz moment”—and Mayes’ project , in general—is to look at its historical context. During the 1920s and ‘30s, the Harlem neighborhood of New York City was home to a growing number of African Americans (many of whom were from the South), whose experiences with racism were conveyed through art, literature, and music. This flowering of Black consciousness also occurred in France, which attracted many students, artists, and intellectuals (not to mention, returning World War I soldiers) from around the globe. The French emblem of equality, fraternity, and liberty must have seemed like a hit of fresh air to people under the yoke of colonization or segregation. Just some of the many ex-patriots were the cultural icon Josephine Baker; writers Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Anna Julia Cooper, Richard Wright, and Barbara Chase-Riboud; artists Henry O. Tanner and Beauford Delaney; and musicians Louis Armstrong, Ada “Bricktop” Smith, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, and Nina Simone.

It is against this milieu that Mayes leads one of SU’s most innovative courses. During the five-week program, students stay at an “apartment hotel,” meet daily at the historic Café de Flore (a favorite of Baldwin’s and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s), visit historical and cultural landmarks, and discuss topics ranging from history and culture to race and identity. “Many conversations revolve around the idea of discernment—seeing what others regard as invisible in Black culture,” she says. “The students rigorously explore the ‘noir’ in French society, as it is expressed in the arts and in everyday life.”

The only program of its kind in the academy, “Paris Noir” is divided into three parts. The first, “On Becoming Paris Noir,” examines the historical, social, and political forces that led to a Black presence in Paris. “To focus on this aspect, we visit various museums and historical landmarks,” says Mayes. “At the Louvre, we study the large glass pyramid by I.M. Pei outside the museum’s entrance and the Egyptian art inside, drawing connections between Africa and the modern French world. We also analyze Picasso’s masks, which capture a borrowed aesthetic from ancient African sculpture, and Géricault’s highly influential ‘Raft of the Medusa.’”

The second part of the course examines the Paris Noir of today. Here, students pour over literary and cultural texts, as well as engage with such Black luminaries as saxophonist Archie Shepp, writer Jake Lamar, poet/activist Sonia Sanchez, historian Pap Ndiaye, photographer Kim Powell, publisher Christiane Yandé Diop, and members of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. (A few lucky students were able to meet singer Nina Simone and witness her last concert in France, months before her death in 2003.)

The third part of “Paris Noir” is an independent research project of the student’s choice. Mayes says this part can often lead to a personal awakening that is gratifying for student and teacher alike. “I want students to have a clearer sense of the beauty and struggle of living somewhere else and then use it to better understand themselves. I want ‘Paris Noir’ to touch them on a personal level,” she says. “Research can provide that catalyst.”

Kishauna Soljour and Tiarra Currie are undergraduates who attended “Paris Noir” last summer. “’Paris Noir’ changed my life as a scholar and a person through a process I call ‘re-learning,’” says Soljour, a junior majoring in African American studies and in television, radio, and film. “In the United States, I had been socialized to accept prepared truth and to regurgitate it, as if it were derived from my own psyche. In Paris, I ‘re-learned’ to question, communicate, and arrive at my own conclusions about my Black identity. As a result, I no longer question who I am. I have become the master of my destiny by accepting my identity with clarity and purpose.”

Currie--a senior majoring in psychology, with a triple minor in child and family studies, early childhood, and sociology—had a similar epiphany. She shares several experiences that reinforced her decision to study abroad, including one involving a panel discussion of Black women that was so moving, it “almost brought tears to [her] eyes.” “’Paris Noir’ exposed me to history like never before,” she says. “I felt like I had learned more about myself in those five weeks than in the past 20 years.”

Currie credits “Paris Noir” for helping her embrace her own Blackness. “I learned that there is no one Black face or Black story,” she continues. “All of us come from different backgrounds and have different complexions and experiences. It this common thread of racism and history that binds us together.”

Open to graduates and undergraduates alike, “Paris Noir” is co-administered by SU Abroad and the Department of African American Studies in SU’s College of Arts and Sciences. (The course is crossed-listed among AAS; English; Women’s & Gender Studies; and the French program in Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics.) Students hail from all over the country, including the universities of Michigan, California, and Pennsylvania; New York, George Washington, Southern, and Howard universities; and Spelman, Barnard, and Agnes Scott colleges.

Samir Meghelli was a junior at the University of Pennsylvania when he enrolled in “Paris Noir” in 2003. Since then, he has returned to Paris many times to conduct research and to lead seminars for SU on the history of hip hop in France. “The ‘Paris Noir’ program has had an indelible impact on my intellectual development and scholarly trajectory,” says Meghelli, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University. “One leaves the program with a far more profound understanding of the global nature of the African Diaspora.”

Meghelli also credits “Paris Noir” for laying the groundwork for his senior thesis; his doctoral dissertation; and his book, “The Global Cipha: Hip Hop Culture and Consciousness” (Black History Museum Press, 2006). “The course is a remarkable way of merging theory and practice, of making Paris our classroom,” he adds.

David Baker G’05, who handles rights and clearances for ABC News, echoes these sentiments. “The program helped me understand race and identity as constructs that shape political, economic, and social discourse,” he says. “It also helped me acquire a broader view of the effects of race and identity, domestically and internationally.” Baker was surprised to learn that many young Parisians’ views of Blacks were shaped by American television, especially rap videos.

It was no coincidence that the Hip Hop World Summit, featuring Missy Elliott and Mary J. Blige, took place in Paris while Baker was there. He thinks the event might have helped dispel some stereotypes surrounding Black women. “It certainly reinforced the concept of music being universal. Regardless of where it is performed, hip hop is used by young people to express their desires and disappointments,” he says.

Baker says that despite France’s liberalism, the country is far from color-blind. “France has had its own racial problems,” he states. “For example, immigrants from former French colonies in North Africa, such as Algeria, have faced high unemployment, discrimination, and a lower standard of living.”

Such disparity likely originated in the early 1500s, when France joined the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Large numbers of Africans were shipped to French plantations over the next four centuries; others wound up in Paris. Abolitionism eventually gained enough of a foothold to have slavery outlawed in France in 1818. Nevertheless, evidence exists of slaves being exported to the French Antilles in the Caribbean as late as the 1870s. “France participated in slavery on a massive scale,” explains Mayes. “But unlike their American counterparts, French slavery took place outside the visual scope of society. Many enslaved Africans worked on huge sugar plantations in the Caribbean.”

The next wave of Blacks arrived in Paris between the 1880s and the beginning of World War I in 1914. This period, known as the “Scramble for Africa,” was characterized by the invasion, colonization, and annexation of African territories by European powers. While colonialism lasted into the 1960s, it was met with widespread resistance. The world wars didn’t help matters, as African soldiers from French and British colonies returned home to find life as colonial subjects hardly better than that of the Fascist or Nazi rule against which they had been fighting. Ignited by the possibilities of French liberalism, many war veterans from the French colonies and the United States made a bee-line for the French capital.

Tess Bonn ’10 says the effects of colonialism became clear last summer, when she enrolled in the course. “’Paris Noir’ changed my life because it gave me the ability to study the impact that African Americans had on the Diaspora, as well as on the arts and culture,” says the English major, whose research focused on the great political cartoonist Oliver Harrington. “It also demonstrated that race and identity can be talked about in a positive way. I don’t think I had ever been as inspired as I was while learning about many the Black men and women who came to Paris [from the United States, Africa and the Antilles], and, in the process, changed the communities around them.”

As “Paris Noir” enters its second decade, Mayes is optimistic about the future. She ultimately hopes to see the creation of a “trans-oceanic corridor,” linking SU with similar academic programs throughout Africa, Europe, and the Americas. These kinds of connections, she hopes, will cultivate alumni and supporters of SU, while stimulating other kinds of immersion opportunities (e.g., internships and co-ops).

“By having a greater understanding of the racial and cultural realities of Europe, our students can view themselves as part of a global community,” she concludes. “I want all of our students to use ‘Paris Noir’ to gain global literacy and to experience the agency that comes with it.”

Samir Meghelli was a junior at the University of Pennsylvania when he enrolled in “Paris Noir” in 2003. Since then, he has returned to Paris many times to conduct research and to lead seminars for SU on the history of hip hop in France. “The ‘Paris Noir’ program has had an indelible impact on my intellectual development and scholarly trajectory,” says Meghelli, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University. “One leaves the program with a far more profound understanding of the global nature of the African Diaspora.”

Meghelli also credits “Paris Noir” for laying the groundwork for his senior thesis; his doctoral dissertation; and his book, “The Global Cipha: Hip Hop Culture and Consciousness” (Black History Museum Press, 2006). “The course is a remarkable way of merging theory and practice, of making Paris our classroom,” he adds.

David Baker G’05, who handles rights and clearances for ABC News, echoes these sentiments. “The program helped me understand race and identity as constructs that shape political, economic, and social discourse,” he says. “It also helped me acquire a broader view of the effects of race and identity, domestically and internationally.” Baker was surprised to learn that many young Parisians’ views of Blacks were shaped by American television, especially rap videos.

It was no coincidence that the Hip Hop World Summit, featuring Missy Elliott and Mary J. Blige, took place in Paris while Baker was there. He thinks the event might have helped dispel some stereotypes surrounding Black women. “It certainly reinforced the concept of music being universal. Regardless of where it is performed, hip hop is used by young people to express their desires and disappointments,” he says.

Baker says that despite France’s liberalism, the country is far from color-blind. “France has had its own racial problems,” he states. “For example, immigrants from former French colonies in North Africa, such as Algeria, have faced high unemployment, discrimination, and a lower standard of living.”

Such disparity likely originated in the early 1500s, when France joined the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Large numbers of Africans were shipped to French plantations over the next four centuries; others wound up in Paris. Abolitionism eventually gained enough of a foothold to have slavery outlawed in France in 1818. Nevertheless, evidence exists of slaves being exported to the French Antilles in the Caribbean as late as the 1870s. “France participated in slavery on a massive scale,” explains Mayes. “But unlike their American counterparts, French slavery took place outside the visual scope of society. Many enslaved Africans worked on huge sugar plantations in the Caribbean.”

The next wave of Blacks arrived in Paris between the 1880s and the beginning of World War I in 1914. This period, known as the “Scramble for Africa,” was characterized by the invasion, colonization, and annexation of African territories by European powers. While colonialism lasted into the 1960s, it was met with widespread resistance. The world wars didn’t help matters, as African soldiers from French and British colonies returned home to find life as colonial subjects hardly better than that of the Fascist or Nazi rule against which they had been fighting. Ignited by the possibilities of French liberalism, many war veterans from the French colonies and the United States made a bee-line for the French capital.

Tess Bonn ’10 says the effects of colonialism became clear last summer, when she enrolled in the course. “’Paris Noir’ changed my life because it gave me the ability to study the impact that African Americans had on the Diaspora, as well as on the arts and culture,” says the English major, whose research focused on the great political cartoonist Oliver Harrington. “It also demonstrated that race and identity can be talked about in a positive way. I don’t think I had ever been as inspired as I was while learning about many the Black men and women who came to Paris [from the United States, Africa and the Antilles], and, in the process, changed the communities around them.”

As “Paris Noir” enters its second decade, Mayes is optimistic about the future. She ultimately hopes to see the creation of a “trans-oceanic corridor,” linking SU with similar academic programs throughout Africa, Europe, and the Americas. These kinds of connections, she hopes, will cultivate alumni and supporters of SU, while stimulating other kinds of immersion opportunities (e.g., internships and co-ops).

“By having a greater understanding of the racial and cultural realities of Europe, our students can view themselves as part of a global community,” she concludes. “I want all of our students to use ‘Paris Noir’ to gain global literacy and to experience the agency that comes with it.”

Media Contact

Rob Enslin