For Future Generations

David Mwambari G’10, who lived through the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, gives voice to present-day refugees.

David Mwambari, originally from Rwanda, first came to Syracuse University in 2008. He recalls hearing from alumni who “urged me to apply as long as I was willing to endure the price paid by Africans coming to Central New York—the frigid winter!”

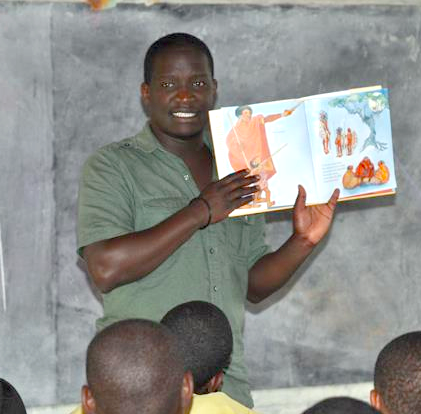

David Mwambari G’10 teaching in Ntenyo School. His approach to community work and education is inspired by AAS Professor Emerita Micere Mugo.

Cold weather aside, the 2010 graduate of the College of Arts and Sciences’ (A&S’) Pan-African studies master’s program credits his time in Syracuse as a springboard for a global scholarly journey.

Mwambari attended high school and college in Kenya. He then earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree in international relations from the United States International University-Africa (USIU-A). While there, he met Professor Anne Abaho, a graduate of Syracuse’s Pan-African studies master’s program who is now dean of social sciences at Nkumba University in Uganda. Abaho recommended Syracuse’s Department of African American Studies (AAS) for its distinguished Pan-African studies program.

Mwambari, now an associate professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences-KU Leuven University in Belgium, recently won a prestigious grant from the European Research Council for work on his project, Traveling Memories, Silences and Secrets: Life narratives of violence among refugees from Africa’s Great Lakes Region. He says the project is inspired by outreach he took part in at Syracuse, as an interpreter for refugees at a Central New York prison and then working with resettled refugee youth in Syracuse-area schools.

We recently caught up with Mwambari to find out more about his journey.

Thinking back on your time in Kenya, how did your experience shape your academic and career goals?

It was very difficult to gain admission into USIU-A because I had to take several exams, which were costly for someone like me who had been working since age 13. It was and still is common for millions of underprivileged youths in Africa to do all kinds of jobs. At the time, I worked as a tour guide, sold second-hand cars and was also a part-time teacher of French and sports.

What was one of the greatest challenges you faced coming to Syracuse?

Given that I grew up speaking French, Kinyarwanda and Swahili, and only having learned to speak and write English when I started at USIU-A, I was not proficient like a native speaker or writer when I came to Syracuse.

Mwambari, center, with fellow students from the M.A. Pan African Studies class of 2010 at Syracuse University graduation.

How did your professors at Syracuse help you overcome that challenge?

They created room for me to improve my academic writing skills with one-on-one tutoring. The first person to do this was Professor Kwame Dixon, an amazing critical thinker and teacher. The Writing Center was another vital resource on campus.

As a professor, how do you think your interactions with faculty at Syracuse prepared you for teaching?

When I worked as a teaching assistant for Micere Mugo, professor emerita of African American studies, she trained me to think of students as human beings who are still growing and need my guidance and compassion.

David Mwambari’s passion for teaching was influenced by his time as a graduate student in the Department of African American Studies at Syracuse University.

Can you recall a particular interaction with Professor Mugo that influenced your teaching style now?

She created space for me to talk about my personal struggles and traumatic issues from my experiences during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and its aftermath. This has helped me deal with students from difficult backgrounds, whether from Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Burundi, Nepal, Indigenous communities in Canada and Australia, or those from poor, predominantly white areas in the mid-west or southern part of the U.S. where I later worked.

Professor Mugo gave me the skills to be human and always remember that others are human, and therefore, to live and teach with a touch of grace. It was this touch of grace and compassion that inspired me to start a community project that healed my traumas.

How did you turn this inspiration into action?

While at Syracuse in 2009, my friends and I started the nonprofit Sanejo, which expands or reconstructs schools in areas rebuilding after war or facing poverty. I led a group of young people from the U.S., Australia, Kenyan and Rwandan diaspora and other countries back to Rwanda to rebuild a school that my grandfather and his community had started in the 1950s. My grandfather was killed and buried near the school with my other relatives during the 1994 genocide. We trained teachers, worked with the students and raised money to rebuild the school. We completed the construction of the campus in 2015 with the help of Syracuse Professor Yutaka Sho and her students from the School of Architecture. The school is now amongst the best in rural Rwanda.

Ntenyo School, built to honor Mwambari's grandfather who was killed there in the 1994 genocide.

What is the mission of your current project, Traveling Memories, Silences and Secrets: Life narratives of violence among refugees from Africa’s Great Lakes Region?

Its goal is to write about the histories of refugees that are often suppressed in the countries where they transit or settle. The idea is to co-create these histories and make some available to the public for purposes including influencing global curricula, policies and community relationships, but also organizing others for refugees’ own private family archives for future generations.

Can you talk about your own outreach work in Syracuse prisons and how that shaped your current project?

In my second year at Syracuse, I helped a refugee from Burundi who was imprisoned and could not speak English. I visited him many times, and we created a friendship. I also started to teach some words of Swahili to those police who were willing. Through his life history, my eyes were opened to the violence that shaped his outlook on life and the decisions he made, including what had resulted in his arrest. My small intervention allowed for the creation of understanding between the police and this man. He got medical care, and we also encouraged his community members to engage with the case, which was later resolved.

Did you have any other influential experiences working with refugees in Syracuse?

I was invited to a dinner to honor the visit of a famous former child soldier Ishmael Beah who was speaking at SU and I sat next to Professor Kristiina Montero, a faculty member in the School of Education. Our discussion touched on many issues, including a project she had recently started working on, focusing on the literacy of young refugee students in a local high school in Syracuse. She asked me if I could join her class, which included only Ph.D. students.

Professor Montero’s class was like no other. It was co-designed with her Ph.D. students and they even asked for my input. It was also challenging as I was learning new theoretical concepts, themes and approaches. I was more comfortable with the practical side of going to high school to work with young refugees from Nepal, Somalia, Burundi and other countries. I was in my last semester and we did so much work, including an exhibition on the SU campus with the refugee students to make these young refugees’ lives visible. With my ability to speak some languages students spoke I was able to get back to my job of being a translator and knowledge broker of cultures and languages. The skills I learned from doing translation, tour guiding and assisting researchers in East African countries before Syracuse were very useful in this instance.

What was your favorite aspect of the Syracuse University experience?

The fantastic faculty, including Professors Joan Bryant, the late Rene Simson, Linda Carty, Herbert Ruffin, Micere Mugo, Horace Campbell and friendly administrators who exposed me to fantastic literature and developed my analytical skills. My Syracuse education transformed my personal and professional life and for that, I will forever be grateful.