Heads and Hearts

Can the health humanities heal what ails medical care?

By Dan Bernardi

Improving the Patient Experience

As Grant explains, students are introduced to literature and the arts as central concepts to the health humanities because they are representations of lives, meanings, concerns, hopes and despair that are changed by illness and disease.

“By learning to read and analyze literature, particularly narratives, the physician or healer will be better able to listen empathetically to the sick person, make meaning of his or her illness story, and decide upon a course of action that best fits into that person’s life, commitments and goals,” says Grant.

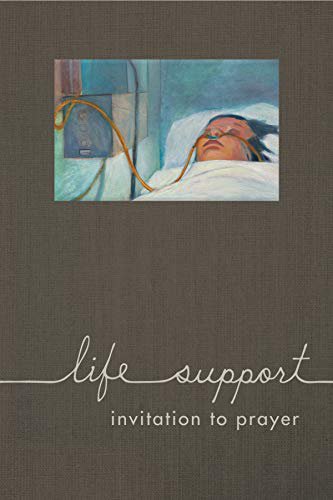

One example of a text that Grant uses in his class is the book “Life Support: Invitation to Prayer” by Judith Margolis. The graphic narrative looks at different meanings of the words “life support” beyond those in the medical setting like the health care team and dialysis machines. By examining this particular narrative, Grant’s class found that other factors like the narrator’s Jewish faith, friends, family and artistic expressions all served to sustain her life as she nurtured her mother through the process of dying.

Taking a look at medicine through readings, podcasts, paintings and even comics reminded Mia Pepi '20, a biology major, of the reasons she wanted to enter into medicine. Pepi was recently enrolled in Grant’s Introduction to Health Humanities course.

“When working with real people, diagnoses and treatments are not clear-cut,” says Pepi. “Health humanities develops skills to understand new perspectives, think in a different way and morally reflect on the numerous relationships encountered when practicing medicine.”

One of the highlights for Pepi was interviewing a patient regarding their experience with a health problem. She and other students learned how to best conduct a medical interview and thoroughly analyze components of the story shared. She explains that the valuable lessons she has learned about the human condition and individual experience of illness will have a lasting effect on her patient interactions throughout her medical career. Pepi now plans to enroll in a master’s program in health humanities during her gap year before continuing on in medicine.

A Nurse’s Empathy on the Front Lines

The need for this curriculum comes at a critical time as physicians and nurses around the world have been stretched thin in the midst of the current coronavirus pandemic. One nurse treating patients on the front lines of a COVID-19 floor at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City shared the importance of keeping in mind the fears of her patients when approaching medical care.

“I always make sure to focus on the positive, step in each room with a smile on and provide a comforting hand,” says Meagan Humphrey, R.N., of New York City. “All these patients are alone since they can’t have any visitors, and it is my job to be their support system.”

Humphrey recalls the story of one patient who was having a particularly difficult time not being able to see her family. “Whenever she got down, I reassured her that I was there for her and she could lean on me for anything that she needed,” Humphrey says. The two built a strong bond, helping the emotional well-being of both the patient and medical professional.

The next day, though, Humphrey was not assigned to that patient, leaving her under the care of a nurse who did not offer the same empathy. “The nurse treated the patient more like a task than an actual person,” she says. “I was in the room later that day and the patient said, ‘I wish I had you again today. You are so sweet and caring, and it meant so much to me. You actually took your time with me instead of just rushing in and rushing out.’” The health humanities is a way for more aspiring medical professionals approach patients with that same level of compassion.

Discovering Meaning

The benefit of the humanities in health care doesn’t just apply to medical professionals. It can also play an integral role in helping the sick person by opening ways of finding meaning in illness and sharing that meaning with others.

“These expressions can come in many forms, from stories to art,” says Grant. “These stories can provide hope for the sick person, their caregivers and loved ones. They can also comfort and inspire others who are experiencing similar ailments.”

According to Grant, another benefit to patients is that they learn strategies to advocate for themselves, their health and their communities in the clinical setting and beyond.

Healing involves more than simply being cured of a disease or ailment. Professionals in the medical/health humanities community believe it is the product of a therapeutic relationship among the health care professional, the sick person and their family members and loved ones. When the patient is open to express what illness means to him or her, it gives the physician or healer a chance to honor the life the patient wants to live. That relationship is the first step to their cure.