Sensing Solutions

Research never stops in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. Each day faculty and students fill the labs and clinics, working with members of the greater Syracuse community to better understand and develop treatments for myriad communication needs. Much of the important and life-changing research happening in those labs is made possible by funding from medical research agencies such the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Two CSD professors were recently awarded prestigious NIH grants. Associate professor Victoria Tumanova is studying how emotional processes might influence childhood stuttering and associate professor Ellyn Riley is exploring how a new method of electrical brain stimulation could help stroke patients suffering from aphasia.

How excitement affects a child’s speech

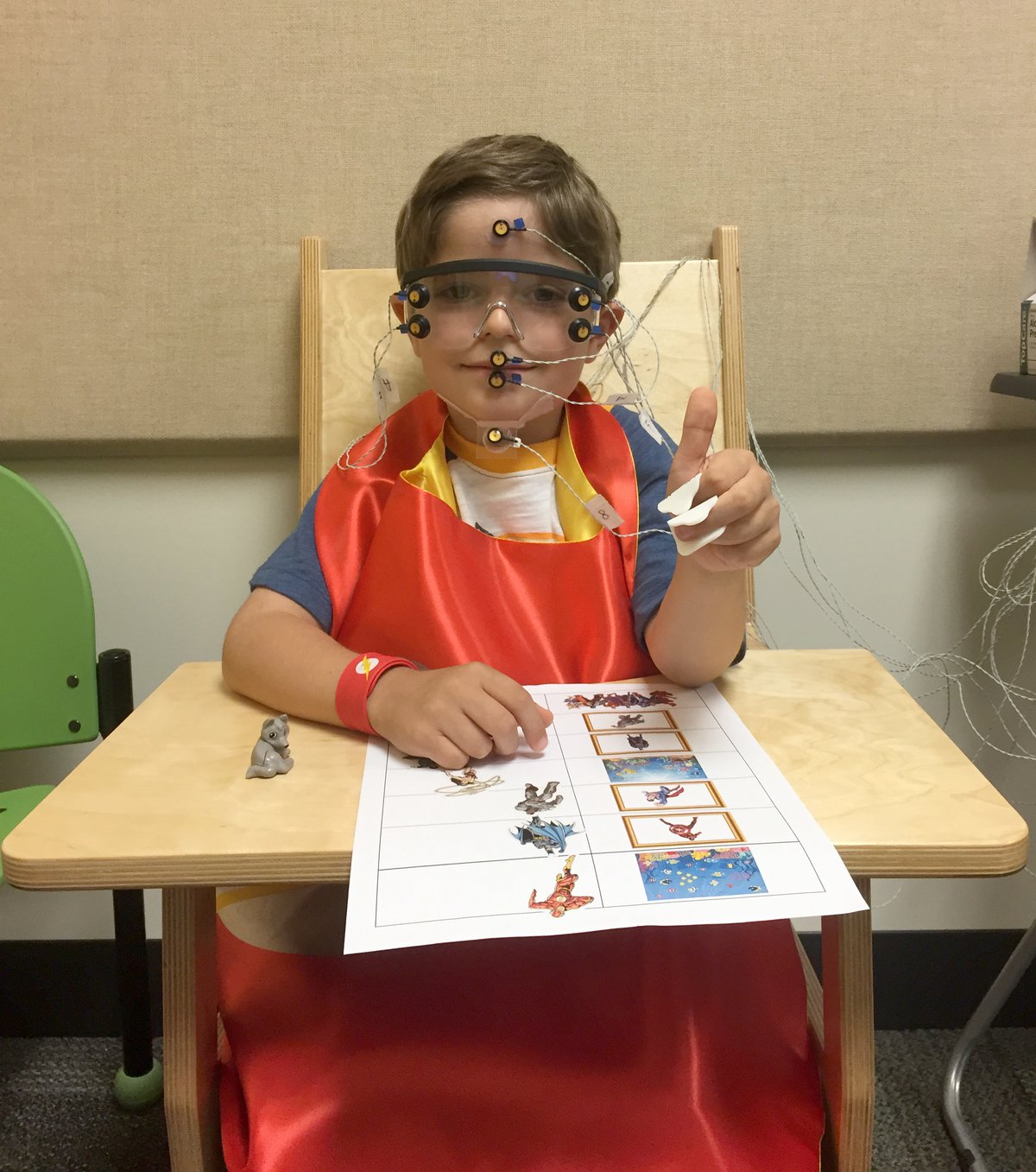

Researchers in the Syracuse University Stuttering Research Lab use sophisticated sensors to track movements of the lips and jaw during speech. (Photo courtesy: Syracuse University Stuttering Research Lab)

What do Hollywood movie production companies and researchers at the Syracuse University Stuttering Research Lab have in common? Each uses sophisticated state-of-the-art equipment like infrared motion tracking cameras and body sensors – but for very different purposes. While the movie production companies use motion capture to animate digital characters, the stuttering research lab is putting it to use on Central New York-area preschool-age children in an important effort to determine what factors lead to childhood stuttering. By tracking movements of the lips and jaw during speech and analyzing data such as skin conductance and heart rate variability, researchers are using the stuttering research lab’s hi-tech equipment to examine the association between a child’s level of excitement and stuttering.

According to Victoria Tumanova, a person’s emotional state can lead to profound changes in their body, including changes in how movements are controlled. “Research evidence from sports psychology and music performance points to adverse effects of stress on skilled movement,” she says. “Speech is a sequence of highly skilled and fast movements. Thus, we predict that speech movement control can also be affected by someone’s level of excitement.”

Victoria Tumanova, associate professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders.

Tumanova serves as principal investigator on a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) exploring the situational factors influencing speech movement control and speech motor learning in preschool-age children who stutter. She is collaborating on the project with Rachel Razza, associate professor in Falk College’s Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, Asif Salekin, assistant professor in the College of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and Qiu Wang, associate professor in the School of Education.

Stuttering is a speech disorder that affects over 3 million people and 5% of preschool-age children in the United States. It is characterized by repetitions of sounds, syllables, or words, and emerges in preschool years during the time when children undergo rapid development of their speech motor control, language and emotional regulatory processes.

Tumanova and her team suspect that stuttering is affected by a child’s “emotional reactivity processes.” Emotional reactivity refers to how easily or intensely someone reacts emotionally to experiences in life. This study is the first to examine the effects of two important types of emotional reactivity processes – contextual and constitutional – on speech in children who stutter and their fluent peers.

The sensors allow researchers to examine the association between a child’s level of excitement and speech motor control. (Photo courtesy: Syracuse University Stuttering Research Lab)

“Contextual emotional reactivity” is someone’s physiological response, such as excitement, driven by a specific situation; it is variable and context-dependent. For example, if a child is at their birthday party opening gifts, they may be very excited; if the child is playing with a familiar toy, they may be calm. She says parents of children who stutter often report that their children stutter more when they experience emotional arousal or excitement, even when it is positive in nature.

On the other hand, "constitutional emotional reactivity" is the person’s inherent way of responding to their environment; it remains relatively stable over time. Some children are more outgoing, and some are more reserved; some children get easily excited, and some do not.

The group hypothesizes that increases in emotional reactivity, driven by the situational context, the child’s inherent way of responding to their environment, or by their combined influence, interfere with speech motor control and speech motor learning processes necessary for the early development of fluent speech.

By determining factors that lead to stuttering early in a child’s speech development, the team hopes to develop strategies to better identify and treat the disorder at its onset. They also expect that the results from this study will inform the assessment of risk factors for stuttering persistence and eventually contribute to improved intervention strategies.

Applying electrical stimulation to stroke treatment

A patient receiving transcranial direct current stimulation at the Aphasia Lab.

CSD researchers are testing a cutting-edge method of electrical brain stimulation to help stroke patients suffering from a language disorder called aphasia. The National Institutes of Health-funded study, led by Ellyn Riley, is currently recruiting participants who have had a stroke in the left side of their brain and who have experienced speech and language difficulties following their stroke.

Riley says this new easy-to-use and low-cost electrical stimulation technology has the potential to boost the effects of the treatment speech-language pathologists are already doing. With the relatively short window of opportunity for rehabilitation for stoke patients, maximizing the effectiveness and efficiency of treatment is essential.

Aphasia affects approximately one third of individuals who have had a stroke. According to Riley, communication for these individuals can be very difficult and each person’s experience with aphasia is unique.

“Some may have difficulty understanding others’ speech and trouble coming up with specific words, whereas others may be able to understand others’ speech just fine, but struggle with speaking slowly and may only be able to produce a word or two at a time,” she says.

Individuals with aphasia usually work with a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) to practice tasks like naming objects, forming speech sounds, or generating grammatical sentences in order to “rewire” the brain as it recovers from the stroke.

Ellyn Riley, associate professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders.

The electrical brain stimulation used in their study is called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). It works by delivering a very small electrical current to specific parts of a person’s brain via sponge electrodes attached to their scalp. The positioning of these electrodes is thought to encourage specific parts of the brain to become active, making it easier for the neurons in those areas of the brain to send electrical signals to other neurons during speech and language therapy.

“By making these brain areas more active during therapy, we can potentially further facilitate the ‘rewiring’ process that is going on in the brain during recovery,” Riley says.

For more information visit the Aphasia Lab website.