Unlocking the "Great Unread"

How the digital humanities are reexamining literature, history and technology.

I. What is Digitization?

One example of using the new to study the old is digitization, or the building of online archives and editions of texts. This can happen through in-person events like transcribe-a-thons, where anyone interested can type and transcribe—transforming analog, hard-copy collections with limited availability to the public into digital assets. The result? What were once perhaps little-known works are now digitally searchable and accessible to many more people. Such events facilitate learning and collaboration as they allow people working in different areas of the humanities to find one another, across institutions and even countries, and spread knowledge to a far wider public.

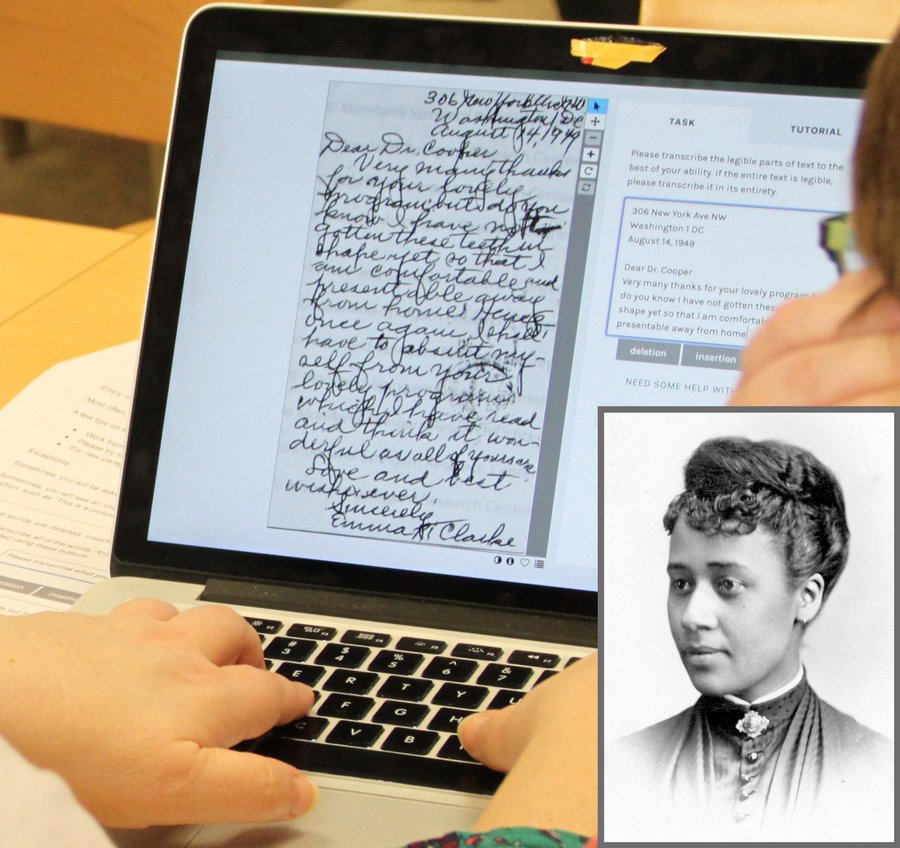

Recently, A&S students and faculty joined in a collective digitization effort and saw firsthand the power of digital tools to illuminate the struggle for equal rights. In February, the Syracuse University Humanities Center celebrated Frederick Douglass Day with a transcribe-a-thon of the papers of Anna Julia Cooper. Cooper was an author, educator, sociologist and one of most prominent African American scholars in U.S. history, being the fourth black woman to earn her doctoral degree when she received her Ph.D. in history from the University of Paris-Sorbonne in 1925. Though her materials had existed in a physical archive, they were not readily available in digital form.

Transcribing Cooper’s works—including papers, notes, diaries and newspaper articles that had previously only existed in hard copy form at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center archives—into a searchable database now allows them to be studied by scholars in many disciplines around the world. The event at Syracuse coincided with similar events across the country, uniting humanities scholars for one common goal. Dozens of University faculty, staff and students gathered at Bird Library and used computers to read facsimiles of Cooper’s documents online and type up the content into a digital database. On that day, 868 pages were transcribed, with 4,586 total classifications in just about three hours, completing about 83 percent of the archive.

II. Filling in the Gaps of Literary History

The creation of searchable archives can answer—and raise—questions in literature or other subjects. By introducing many previously unfamiliar works to researchers, it can lead to a revised understanding of a subject’s history.

“While our sense of literary history has typically been based on the comparatively small selection of books published, these databases offer an opportunity to peer into what one person has called ‘the great unread,’ all those books that were published in literary history which we have not previously paid attention to,” Forster says.

This allows scholars to study, compare and contrast a wider range of books with the simple click of a mouse. As Forster explains, this information can be used to perform statistical analysis that evaluates literary trends like the history of book titles.

“Titles were once very long, but grew shorter over time,” Forster says. He explains that the full title of the novel we normally call Robinson Crusoe was The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver'd by Pyrates. While that was published in 1719, Jane Austen’s one-word-titled novel Emma was published less than 100 years later. While researchers do not yet know the reason for these shorter titles, digital analysis has opened up a new area for future inquiry.

Similarly, researchers can use statistics to test authorship by examining vocabulary usage. For example, the actual author of the novel Teleny is unknown although this book from the late 1800s has long been attributed to Oscar Wilde. Forster notes it could be possible to confirm or deny his authorship by using powerful algorithms to test the novel’s sentence structure and vocabulary to other Oscar Wilde novels. Just as new techniques in art scholarship can help determine the creator of a painting, this new form of literary analysis has the potential to answer questions long thought unanswerable.

IV. New Integrated Learning Major

Students in the new digital humanities Integrated Learning Major (ILM) creatively, critically and ethically dig deeper into this wide range of topics. Launched in spring 2020, the ILM allows students to explore the intersections of their primary major and digital technology. It combines a traditional major with newly developed coursework in digital humanities. A key learning goal is for students to learn how “old” and “new” approaches in digital humanities can illuminate contemporary and long-standing ideas.

One new class taught by Forster that will fulfill the technical skills requirement of the ILM, and introduce students to the intersection of computer programming and the humanities, is English 221: Humanistic Computing. In this interdisciplinary offering, students learn the basics of the Python programming language; explore “poem generators,” which are computer programs that combine user-generated words and phrases to create poems automatically; and read the history and social questions surrounding computer programs.

“In trying to combine a sense of history and context for computing, this course exemplifies what I hope the DH ILM can do,” says Forster. While digital humanities can be used as a tool in the service of the humanities, at the same time they can be an object of humanistic study.

Students take 21 credits in a variety of topics:

- Three courses (nine credits) focused on the uses of digital technology in the humanities and how the history of technology affects art, literature and culture;

- One class (three credits) which will fulfill a “technical skills requirement” by taking a computer programming class;

- Two electives (six credits) selected from courses in the humanities where the study or use of technology plays a significant role and;

- A three-credit senior capstone project.

Acquiring this broad and deep understanding will prepare students for a diverse range of opportunities after graduation that require digital skills and knowledge of the human experience. Forster thinks graduates could be thought of as "translators" between different project groups, in fields where a deep understanding of technology is necessary. In short, digital humanities are a flexible but strong foundation for jobs of the 21st century that may or may not even exist yet.

While the digital landscape is ever-changing, the role of the humanities—where interpretation, historical thinking, critical thinking and contextualization are key skills—endures even as it takes on new forms. Thanks to the welcome perspective and new knowledge made available through the digital humanities, A&S students will be equipped to answer today’s pressing questions for a more hopeful and humane tomorrow.